Column | Former bureaucrat's new book casts fresh light on Kerala's industrial ecosystem

Mail This Article

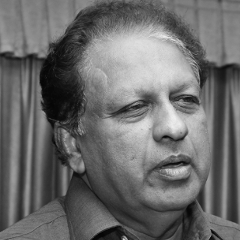

C Balagopal, an IAS officer, who resigned from the coveted service, became a highly successful entrepreneur to set up the largest blood bag system in the world. He later exited the job to become a management guru in great demand, the Chairman of the Federal Bank, an author and a philanthropist. His fourth book, ‘Below the Radar’ is an account of his remarkable journey, which contends that his success story is not sui generis, but the result of the development of an ecosystem in Kerala as a result of the evolution of public policy in the state under different governments. He has presented a case study of his own venture and a similar world-class steel castings maker to prove the point.

He has also characterised nearly 50 other enterprises, scattered all over Kerala, as having overcome the problems of the state to become first-rate technological enterprises, mostly in rural areas. According to Balagopal, the entrepreneurs in question took advantage of the favourable factors, that were put in place, thanks to the public policy initiatives and led to the emergence of a cohort of companies, which have grown to national and global scale.

Refreshing change over the decades

As anticipated by the author, the book has led to much debate, discussion and controversy because the anecdotal evidence has created the impression that Kerala is not investment-friendly, it is infested by corruption, nepotism, bellicosity of trade unions, hartals and other evils. The memory of a remarkable movie called “Varavelpu” (welcome ceremony), which the then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee called the stereotype of the plight of investors in Kerala, still haunts the popular minds. The author acknowledges this and even confesses that he had his own share of problems at the initial stages. Perhaps, his status as a former IAS officer enabled him to overcome these hurdles. His company had trade unions, but he never lost a day on account of strikes. He and the other successful entrepreneurs managed to run their enterprises without the proverbial difficulties in managing them in Kerala. “The state has a reputation of being plagued by labour problems. Probably, there were reasons for that. But over the last 30 years, things have changed,” Balagopal says.

But a few exceptions can't alter ground reality

The critics of the book argue that the companies cited by Balagopal were exceptions which only prove the rule. Taken as a set phrase, “the exception that proves the rule” indicates a deviation from the norm, a challenge to the stereotype. It says, in effect, the norm or stereotype is the rule and here is something that is an exception to that rule. It carries the assumption that the rule remains intact.

Balagopal’s hypotheses are, however, worth studying because if he is right, Kerala is very much on the road to industrialisation. If Kerala, while undoubtedly having several drawbacks, has certain positive features that work to support high-tech industry, understanding these success stories will help us to design better policy initiatives. The common features in the 50 companies are they all began small, all faced initial hurdles, all had stress on technology, all had technically qualified people and all had markets abroad.

Sustainability is the key

Sustainability is an important feature in industrial development. Success stories which disappeared within short periods will not inspire confidence in others. The sagacity of Chief Minister C Achutha Menon inspired many talented people to come to Kerala and build institutions like Keltron, but today, Keltron survives on commissions earned by procuring goods from private suppliers and supplying them to Government Departments. Do we still have talented people flowing into Kerala? If public policy was conducive to industrial development, why has it not been sustained?

Horror stories still abound

I have heard many who came to invest in Kerala telling horror stories of their experience as investors even at investment promotions abroad, making it counterproductive to hold these events. Stories are legion about investors having been driven away even after they were making profits, not to speak of those who went away to neighbouring states after surveying the scene. Perhaps, the successive governments did not keep the momentum of public policy changes as their priorities and did not create a favourable ecosystem for public or private investments to succeed.

Latest trend is a pointer

Of late, the trend is for Keralites to seek their fortunes abroad rather than to return to the state. With the exodus of students at an early stage for education and employment abroad, the availability of trained personnel may even become more scarce.

Lessons from the book

Considering that the book is well motivated and honest, the only hypothesis we can arrive at is that the success stories belong to a number of dedicated individuals, who were able to fight the system and succeed, but others became the unfortunate victims of poor governance, which could not sustain the momentum generated by public policy. This is in spite of the fact that several indices have placed Kerala higher than the more advanced states like Gujarat on occasions.

The book is certainly a clarion call for a detailed study on the favourable and unfavourable factors that determine the state of industrialisation in Kerala to remove the cobwebs of cliches and anecdotal information which cloud our judgment. If such a study reveals the silent emergence of a favourable ecosystem across the board, the author will have done a yeoman service to his home state. The startup ecosystem developing in technoparks and elsewhere in Kerala could also be studied in this context.