Analysis | 2024 polls a repeat of 1967? How?

Mail This Article

There was a turnaround in the character of Indian elections in 1971. It was a ‘One-leader One slogan’ polls. The ‘One slogan’ was 'Garibi Hatao' and the leader was Indira Gandhi. The Opposition parties joined in a Grand Alliance. Indira Gandhi-led Congress won two-thirds majority. The 1977 elections were also a first of sorts -- it was the first in which the Congress party, which had till then not lost power at the Centre, was ousted by a powerful political wave in the northern states.

Each of the subsequent elections was unique in its own way. Some were predictable and others were determined by factors which defied many a pollster.

Cut to 1967, elections to the Parliament and the state assemblies were held together. India had ‘One Country- One Election’ till 1971 (except perhaps in Travancore-Cochin and Kerala, which had mid-term polls in 1954, 1960, 1965 and 1970 respectively on account of ministries failing to complete their term).

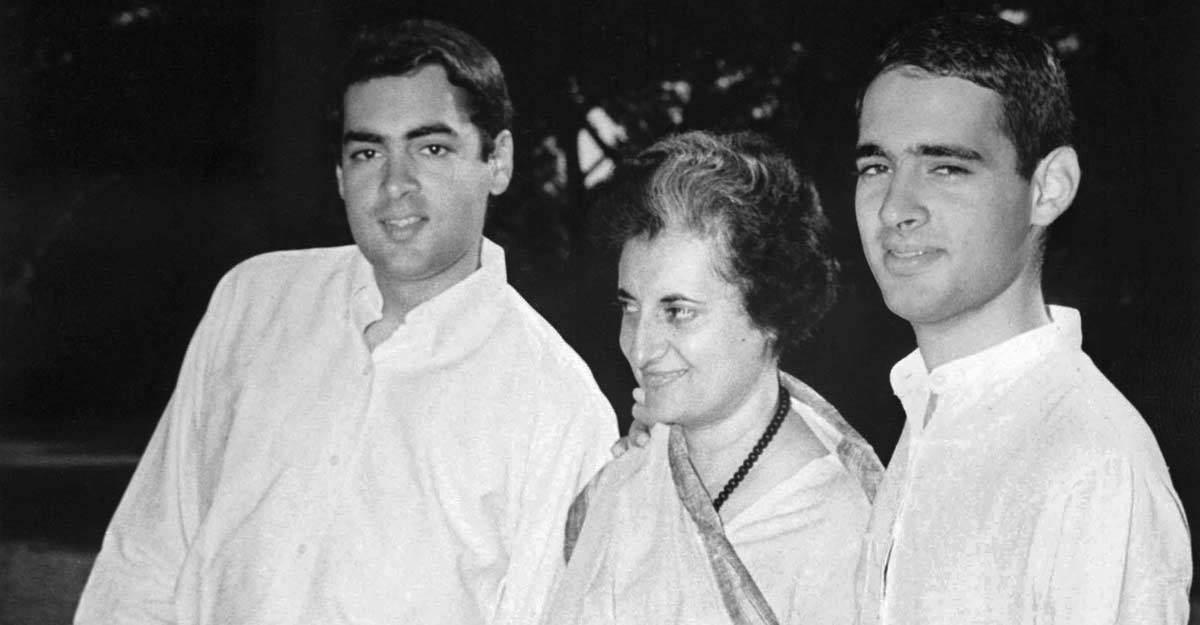

The 1967 elections were the first after the demise of Jawaharlal Nehru. The Right and Left wing parties in the Opposition had joined at the state level to oust the Congress. The move was successful in eight states with the support of some leaders who had come out of the Congress. The majority of Congress at the Centre was reduced to a mere 21, which was quite an event then. The subsequent instability of the coalitions at the states’ level is another story.

The emerging class of middle peasantry was discontented with the Congress regime. Powerfully articulated by Chaudhary Charan Singh, the discontent was translated into votes and the Congress lost power in Uttar Pradesh. The economic problems like price rise, unemployment and rural distress had come to the fore by the mid-1960s. First time, the national election became an agglomeration of local political factors compounded by the impact of broad economic issues. The 1967 elections did not have a powerful slogan. Indira Gandhi was still emerging as the leader and the Congress organisation was powerful. The governments at the Centre and the states had assumed different political colours for the first time since Independence.

Does something similar come to mind when we look at the present scenario, albeit with differences, which also are marked. That is why we call 2024 a faint repeat of 1967 elections. There are several states already run by the Opposition parties. Local political, caste and economic issues (which of course have a pan-Indian dimension) were quite prominent in 2024 elections.

Like the Congress of 1967, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is in the pole position of Indian politics. But unlike 1967 when the Congress could retain power on its own, the BJP lost its single party majority in 2024. Coalitions at the Centre, which had become a feature of Indian politics after 1989, has returned.

Another point to note is that the BJP has a leader in Narendra Modi, whereas Opposition projected none. But winners in 1977 and 2004 also had not projected a leader.

And in 2024, like in 1967, there was an agglomeration of local factors, and its outcome is based on this. In Odisha, the two-decadal fatigue with the ruling regional party led by Naveen Patnaik helped the BJP gain seats in the Assembly and Parliament. The ally Telugu Desam, whose support is critical for the BJP, won a landslide victory in Andhra Pradesh cashing in on the anti-incumbency against the state government, led by Yuvajana Sramika Rythu Congress Party (YSRCP), a regional outfit that had broken away from the Congress.

Another critical ally of the BJP, the Janata Dal (United) in Bihar won 12 seats because of state-specific factors. Such reasons can be seen in every state, from Kerala to Kashmir.

In short, 2024 elections have been an ‘agglomerative’ one, however much the BJP tried to make it a precursor to ‘One Country-One Election’. The elections of 1967 were ‘agglomerative’. In the 2024 elections too, star campaigners, including the Prime Minister, spoke in different states taking into consideration matters of local importance, probably realising its agglomerative nature.

One pertinent question that arises in the post-2024 election scenario is whether the coming back of coalitions would add strength to federalism in India.

The immediate period after 1967 did not do so and the Indian polity relapsed into strong centralising tendencies in the 1970s. In the present elections, there is marked difference in state-wise electoral trends. Will the thanksgiving come in the form of special packages and discretionary grants?

If that happens, the coming back of coalitions will be a setback to basic federal principles, in which transfer of funds should desirably be non-discretionary in a substantial way. If political bargaining power becomes the prime consideration, it will take the place of objective assessment of needs.

India has proved its unity in diversity again. Coalitions are a natural consequence of the need for unity amid diversity. Its impact on federalism -– whether it helps it to bloom or makes it wilt -- remains to be seen. Election of 2024 has been ‘agglomerative’, propelled by a clutch of state-level issues than a single central narrative.

It is better that the principle of federalism is preserved -- else a different agglomeration is likely to throw more surprises in a future election.

(The writer is a former Indian Revenue Service officer, author and freelancer)