Warrier: Innovative warrior in Kerala murals’ critical juncture

Mail This Article

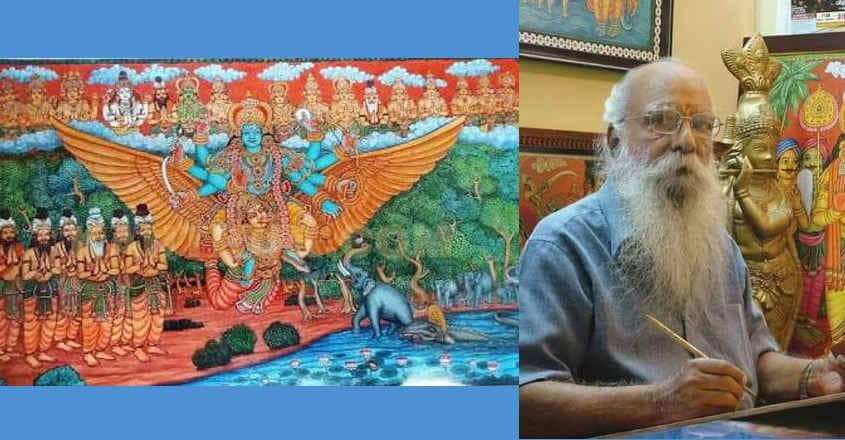

K K Warrier was 83 when he took up an artwork that ended up to be his last in a career spanning six decades as a Kerala-style muralist. The bespectacled veteran with flowing grey beard painted the mystical Hindu tantra diagram of Sreechakram last year at a historical palace down the coastal state, a good 450km south of his native place.

The cultural dimension of the artist’s work on a wall of the heritage structure in Kilimanoor near Thiruvananthapuram has much more than just that of a Malabar-born man working in erstwhile Travancore. For, it was in the ancestral home of none other than Raja Ravi Varma that he sketched the Sreechakram featuring a definite number of interlocking triangles around a central dot called bindu.

Ravi Varma, as a celebrated Malayali painter from the 19th century during which he blended European techniques with Indian sensibilities, has had a definite influence on Warrier since his early strokes with brush. That element of light-and-shade and a tendency to lend a three-dimensional touch to his images were what actually made the muralist’s work distinct from his fellow professionals. Thus, to do an ancient-era abstract work representing the cosmos with the human body at the princely residence of a bygone pioneer known for his realism was a pleasantly strange tribute. Warrier died at the age of 84 this week, marking the exit of the last of the few masters who revived the Kerala genre of traditional murals that was facing an acute existential crisis towards the end of the 1980s.

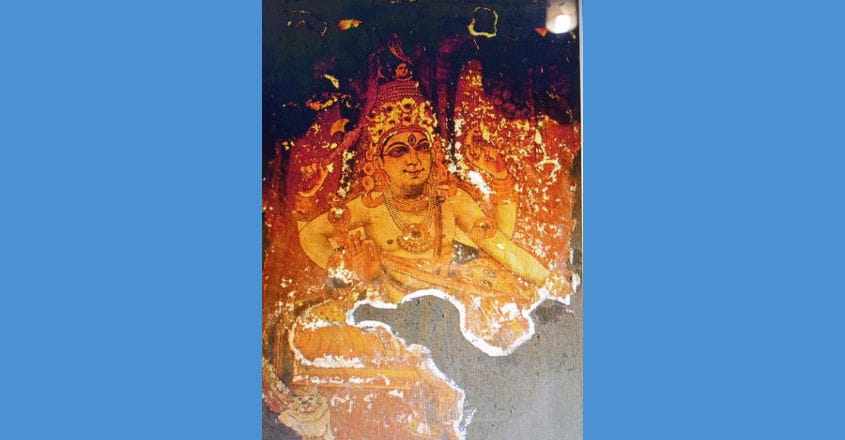

For, that was a time this art was suffering from an extreme dearth of practitioners. The gloomy scene was a far cry from its hoary days between the 9th and 12th centuries AD when a long string of Hindu shrines from Gokarnam to Kanyakumari had their walls getting ornate with mythological scenes depicted in a unique colour code and tight use of space. Ravages of time and poor patronage had over the years faded those images — partially, sometimes even completely. In several Kerala temples and palaces, they looked morosely dim by the turn of the 20th century, while at many other places the invaluable images had vanished completely after the 1960s due of mindless whitewash by administrators with little sense of heritage.

Simultaneously, a handful of masters had by then begun conservation of murals across the state. Typically, using only natural pigments and brush-leaves on walls that have to be meticulously tempered before applying paints layer after layer. Among them was Kizhakkedath Kunhirama Warrier, simply KK, who was born in 1934 at Mattannur in what is now Kannur district. Not too far from that semi-hilly locality, a young Warrier had in 1955 begun assisting his art guru C V Balan Nair at the Sreerama temple Thiruvangad. The shrine had its walls warranting renovation of the murals and they master and his disciple were deputed for the task that requires not just artistry, but conservation skills.

Untiring journey

From then on, it has been a long and meaningful journey for Warrier. And untiring, till the end. As aesthete P T Bhaskara Poduval notes, it took only ten days for octogenarian Warrier to complete the Sreechakram at the natakashala annexe of the Kilimanoor palace. “That was alongside an exhibition of his works in the venue,” he recalls, fondly.

Warrier died on August 6 at a hospital in Thrissur. That city, often called Kerala’s cultural capital, is 30km southeast of Guruvayur, where the artist had spent a defining part of his life. The busy pilgrim town has the famed Srikrishna temple, where Warrier worked for three years from 1986 to complete a project with two other frontline artists. When all three sides of the sanctum sanctorum got painted afresh with murals, the shrine got a facelift it merited after a massive 1970 fire had destroyed the entire complex.

That art exercise also ushered in a new chapter in the modern history of south Indian frescos. Kerala got an Institute of Mural Painting in 1989, courtesy an endeavour by the Guruvayur Devaswom Board that administers the temple. One of the students in the first batch of its five-year course is K U Krishnakumar, who is currently the principal of his alma mater. He, as a boy, recalls how Warrier had been an influential presence in the traditional mural circuits with firm grip over both the theoretical and practical aspects of the ancient art.

“Warrier’s style was a tad different from the other two titans who painted the Guruvayur temple,” points out Krishnakumar, referring to his late guru Mammiyur Krishnankutty Nair and M K Sreenivasan (from whom he succeeded as the institute’s principal). “Unlike with the others, including the renowned Pattambi Krishna Warrier, there’s an unmistakable streak of realism in KK’s paintings. He gave that extra touch that made some faces and the body he drew look more appealing to the masses.”

This is an observation that finds endorsement from the late artist’s son Sasi Warrier, also a mural painter. Based in Kochi, where Warrier spent much of his life as a teacher with the city’s Kendriya Vidyalaya, Sasi notes that his father was of the opinion that art, however stylised, should be accessible to the common people. “Murals can be representative of the aesthetics of a bygone era, but the younger generation too should be able to appreciate it,” he says, recalling the motto of the senior Warrier, who had won the Kerala Lalithakala Akademi laurels three times.

Immersed in world of murals

Sasi, who now heads the Indian School of Arts his father had founded in Kochi, notes that Warrier was as placid a man at home as he was in public circles. “His basic passion was art; that was his obsession. He was a family man, but seldom keen to micromanage domestic matters. He loved us, but very quietly without being eager to show it off,” trails off Sasi about the artist, who was “very systematic” even about routine things like cleaning the plate after lunch or combing the hair before going out.

Mural institute’s Krishnakumar chips in to say Warrier bore a meditative air around him. “He was completely immersed in the world of murals. I have seen him seldom speak of anything other than paintings, leave alone a trace of light joke or gossip,” adds Krishnakumar, a Krishnakutty Nair protege. “My guru, Warrier and Sreenivasan shared a very warm relationship, but they also knew how to maintain it by not intruding into the others’ territories. We youngsters used to find it amusing and curious.”

The calmness around Warrier is something that critic-writer C P Unnikrishnan Menon, too, agrees. The Kochiite recounts with gratification the English translation he undertook for a Malayalam book Warrier wrote about his trysts with art and experiences as a muralist. “Warrier would send me the matter in instalments; I would enjoy my share of the task. It lasted for no less than two-and-a-half years,” Menon says about the bilingual 319-page work that came out as Chithravisheshangal in December last year.

Educationist Menon, also a Kathakali performer and columnist, says that he also had plans for a similar exercise with Sanskrit treatises like Chitrasuktam and Chitralakshanam that Warrier, well versed in the ancient Indo-Aryan language, had translated into Malayalam. Warrier had also done a monumental artwork called ChithraRamayanam by the turn of this century. That is another project that Menon plans to step in by translating its inspirational shlokas into English, which “as an international language has a global appeal that Kerala murals deserve”.

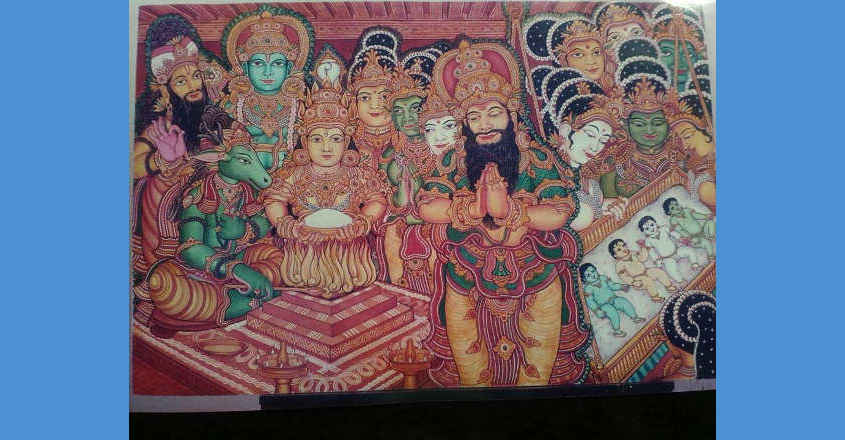

It was in Kochi’s Sitarama Kalyanamandapam in downtown Ernakulam that Warrier worked on a mural portraying the marriage of the hero and the heroine of the epic Ramayana. The assignment was undertaken in the second half of the 1980s when the artist was parallely working at two other venues: Ravipuram temple nearby and then at Guruvayur. Much later, in 2015, Sasi undertook a clean-up of that Sitarama mural. For that, he had support from painter-cartoonist Manoj Mathasseril, a Warrier disciple. “I find it a matter of bliss,” says Manoj, 49, a mechanical engineer, about the exercise that required delicate washing of the wall using acid. “What more can be happier for somebody to deck up a work of one’s own teacher!”

Manoj was into the last lap of a documentary film on Warrier when his master died. “I have been into it for the past four months, taking Warrier down memory lane as well as to some of the places which he actually traveled,” he reveals about the proposed 45-minute movie with the Paliyam temple at Chendamangalam west of Aluva as one of its key locations (as Warrier’s one-time haunt). “We had plans to take him to a few more shrines where he had spent time painting. That we will still go, but now, yes, without him.”

Care for art

Warrier had not just been painting anew or giving freshness to frescos in temples. He had also been into conserving art majorly but pealing out ancient frescos from walls that were anyway set to be pulled down or found beyond repair. In fact, Warrier, went on to salvage almost a 100 such murals by taking out them fully or partly and pasting the flakes on canvases that are transportable. Thus in 2012, Warrier held an exhibition in Kochi of 98 of such near-abandoned murals from several Kerala temples such as ones in the districts of Ernakulam, Thrissur, Malappuram, Kozhikode and Kannur, besides from places down the state. The collection and display specially impressed mural scholar M G Sashibhooshan, who hailed Warrier’s sustained efforts to bring to public domain artworks that the world would never have seen otherwise. “Those murals, particularly some from Alathiyur temple in Malappuram district, are priceless,” notes the Thiruvananthapuram-based author-historian. “Their intricacies and ornamentation are distinct and amazing.”

The typical Kerala mural, known for its characters virtually jostling for space and having penchant for decorative to the maximum, is a genre seen in temples, vintage churches and big feudal-era mansions that the state’s only institute teaching the art sticks to methodically. At Guruvayur, Krishnakumar, as the school’s head now for almost two decades, reminisces his first meet with Warrier. “That was when we had just begun studies in the institute. As part of the course, we were taken to see murals in places north and south of the state,” he says. “In end-1989 or early 1990, the state government held a cultural symposium in Thiruvananthpuram. Mural paintings had a session in the event at Veli. A talk that Warrier gave was an eye-opener for us beginners as well as the seasoned figures in the field.”

Today, if murals have come out of their obscurity and begun enriching even the walls of star hotels, providing employment to its painters in movie as art directors, archaeological conservators and schoolteachers, K K Warrier does have a role in the bright change of scene. It’s a cutely layered story.