Column | A glance at the past and present Fab Four

Mail This Article

The fortnight that went by saw two amazing Test matches in New Zealand, where the hosts managed to eke out thrilling victories. They triumphed over England at Basin Reserve, Wellington, by one run, the narrowest of margins, and managed to edge out Sri Lanka off the last ball of the game at Christchurch to record a two-wicket win. New Zealand's win over Lanka also ensured India's qualification into the final of the World Test Championship, to be played against Australia at The Oval, London, from June 7.

One common factor in both these victories was the role played by former Black Caps captain Kane Williamson. He had anchored a comeback for his side in the game against England by striking a superb century in the second innings after they were forced to follow on by the visitors. At Christchurch, he started by playing second fiddle to the in-form Daryl Mitchell, only to step up the pressure on the pedal once the Sri Lankan bowlers broke their partnership. The manner in which he navigated the team through the tense last over and the fantastic dive he executed to reach the crease to score the winning run showed his class and character.

But the fortnight did not belong to Williamson alone. Virat Kohli emerged out of a long lean spell with the bat to hit a century at Ahmedabad against the Aussies. This was not a typical Kohli innings where he dictated terms to the bowlers, instead he pulled down his cap and showed a new facet of his batsmanship by scoring the runs in ones and twos and wearing down the bowling on a pitch where ball did not always come on to the bat. Joe Root had a brilliant outing at Wellington scoring an unbeaten 153 in the first innings and following up with 95 in the second, which brought England very close to the target. Steve Smith could not do much with the bat, but he plotted and guided Australia to a win in the third Test of the series against India at Indore after his team was decimated in the first two matches. Smith grabbed the opportunity that came his way when Pat Cummins, the regular skipper, was forced to return home and used it in full measure to display his acumen and astuteness while leading the side.

The fabulous four of Kohli, Root, Williamson and Smith have dominated the batting charts in international cricket during the last decade. The timings of their careers have coincided with all of them making their debut in the period between 2010 and 2012. Each of them have played more than 90 Tests - Root having played the most (129), followed by Kohli (108), Williamson (96) and Smith (93). Smith had to serve a one-year suspension from March 2018, onwards, for his role in the ball-tampering incident in the Cape Town Test against South Africa, while Williamson’s lesser number are on account of the fewer matches that his country plays. But Smith leads the pack with 30 centuries, with Root (29), Kohli (28) and Williamson(27), breathing down his neck. All four had led their respective countries and proved to be successful leaders, only to step down from this pedestal later on.

How unique is this phenomenon of four cricketers, all batsmen, hailing from different countries, yet contemporaries, rising to the pole position in their specialist area in the same period ? A look at cricket history will tell us that a similar occurrence had happened during the 1980s when when four players from different nations held the centerstage in international cricket. The only difference from the present situation was that the champions who hogged the limelight were all-rounders, who could contribute in an equally effective manner with both the bat and the ball. Thus, their overall impact on the course of the matches they played was substantially higher than those of cricketers whose prowess was limited to either wielding the willow or hurling the red cherry.

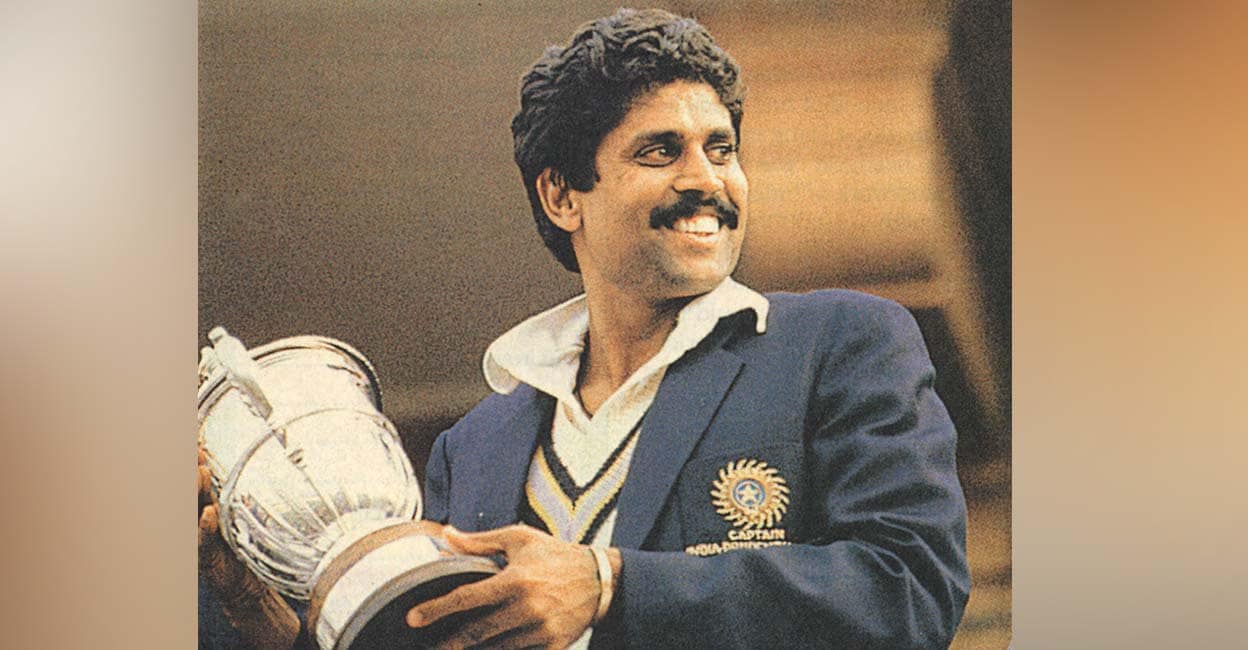

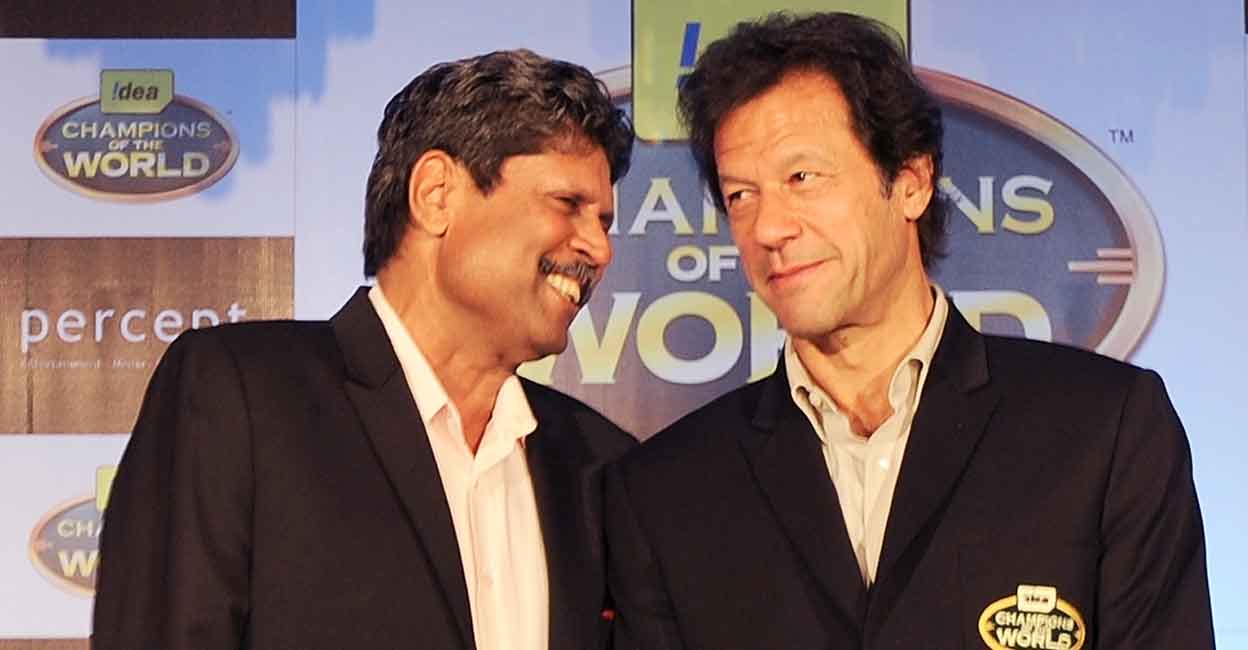

Kapil Dev, Ian Botham, Richard Hadlee and Imran Khan dominated international cricket for most part of the 1980s. They were primarily fast bowlers, who relied upon seam and swing bowling to pick up wickets. In addition to this, they were also exciting batsmen, who could turn the course of a match single-handedly through their skills at destroying and decimating opposing bowling attacks. Three of them, with the exception of Hadlee, led their national sides too, with Kapil and Imran leading their sides to World Cup wins as well.

Among the four, Imran was the first to make his bow into the hallowed portals of Test cricket. He played for Pakistan against England at Birmingham in 1971 as a rookie, bowling a few overs and batting at No. 11, without making much of an impact. He took a break to pursue his studies at Oxford and returned to the national side in 1974 as a a much improved player. At his best he was unplayable as his armoury was replete with in-swingers, reverse swinging yorkers and carefully directed bouncers. His haul of wickets in Tests would have been much higher than 362 wickets but for he being forced to stay away from the game on account of a stress fracture of shin when he was at his peak during period from 1983 till 1986. He grew by leaps and strides as a batsman during the latter part of his career and could command a place in the playing eleven solely on account of his skills with the willow. He was a brilliant leader and moulded the talented, yet enigmatic and temperamental, bunch of Pakistani players into a fighting outfit, which could be ranked amongst the best in the world.

Hadlee was the best bowler amongst the four and he honed his skills to perfection as the years progressed. After starting out as a tearaway fast bowler, he cut down on his speed to focus more on cut and swing and acquired mastery over them. He was the spearhead of the New Zealand attack and such was his skill that he could find purchase on all types of pitches. Though he played during a period when his country did not play in many Tests, Hadlee became the first bowler to take more than 400 wickets and finished his career with a haul of 431 scalps. He was a useful batsman as his record of 3,124 runs in Tests, with 151 not out as his highest score would indicate.

No player had swung the fortunes of a Test match so decisively on as many occasions as Botham did when he was at his peak. The Golden Jubilee Test that India played against England in 1980 was one such occasion when Botham single-handedly demolished the Indians by scoring 114 runs in the only innings he batted and taking 13 wickets for 106 runs. Australia were at the receiving end of his brilliance when their squad under Kim Hughes toured England in 1981. Botham could swing the ball prodigiously and trouble even well-settled batsmen by the late movement he could generate irrespective of the condition of the ball and type of pitches he bowled on. He was unfortunate during his stint as captain since England played the mighty West Indies in 12 of the 14 Tests where he led the side. This was made worse by the fact that captaincy affected his flair as a player as seen by the distinct dip in his performances when he was at the helm. Botham was also the most colourful amongst the four in that he was not averse to blowing smoke rings at the authorities and calling a spade a spade.

Kapil was a supremely talented athlete who broke the myth that India could not produce fast bowlers. He was the last among the four to break into the international arena but quickly established himself as one of the leading all-rounders of the times. Despite playing most of the matches in the dry, unhelpful pitches in the sub continent, Kapil could pick up wickets by the dozen and overtook Hadlee’s tally to merge as the top wicket-taker in Test cricket. He was an attacking batsman who came good when pitted against a challenge of overwhelming proportions as happened at Turnbridge Wells during the 1983 World Cup when he struck a scintillating unbeaten 175 and at Port Elizabeth in South Africa in 1991 when he scored a superb 129 even as wickets crumbled around him. As a captain, he was not shrewd nor was he a strategist, but he believed in setting a personal example which inspired others. The zenith of his captaincy was leading India to victory in the 1983 World Cup, an event which resulted in re-charting the course of the game.

All of them ended their careers during the early part of the last decade of the previous century. Hadlee was the first to hang up his boots, in 1990, followed by Imran and Botham, who both announced their retirement in 1992, within a few months of each other. Imran had announced his decision to quit after the 1987 World Cup and even stayed away from the game for more than an year till he was coaxed by Gen Zia Ul Haq, then military ruler of Pakistan, to get back and lead the national side. Kapil was the last to leave, managing to stretch his career till 1994, by which time he was a pale shadow of the giant he used to be on the field.

Thus, it can be seen that the present quartet of top batsmen emerged almost two decades after the retirement of the four great all-rounders. When will the next foursome of this nature emerge and who will they consist of? And what will be their area of specialisation? These are questions that will be at the back of the minds of followers of the sport as they sit back to savour with relish the masterpieces on offer from the willows of Williamson, Kohli, Root and Smith.

(The author is a former international cricket umpire and a senior bureaucrat)