Pandalam royals and Ayyappa myths

Mail This Article

It was nearing noon but the precolonial buildings and lawns around Valiyakoickal Sree Dharmasastha Temple in Pandalam felt fresh and dewy on October 23. During the past few days, the sky was cloudy and there were intermittent heavy showers. This was the place, along the banks of Manimala river, where Lord Ayyappa is believed to have spent his childhood some 1,000 years ago.

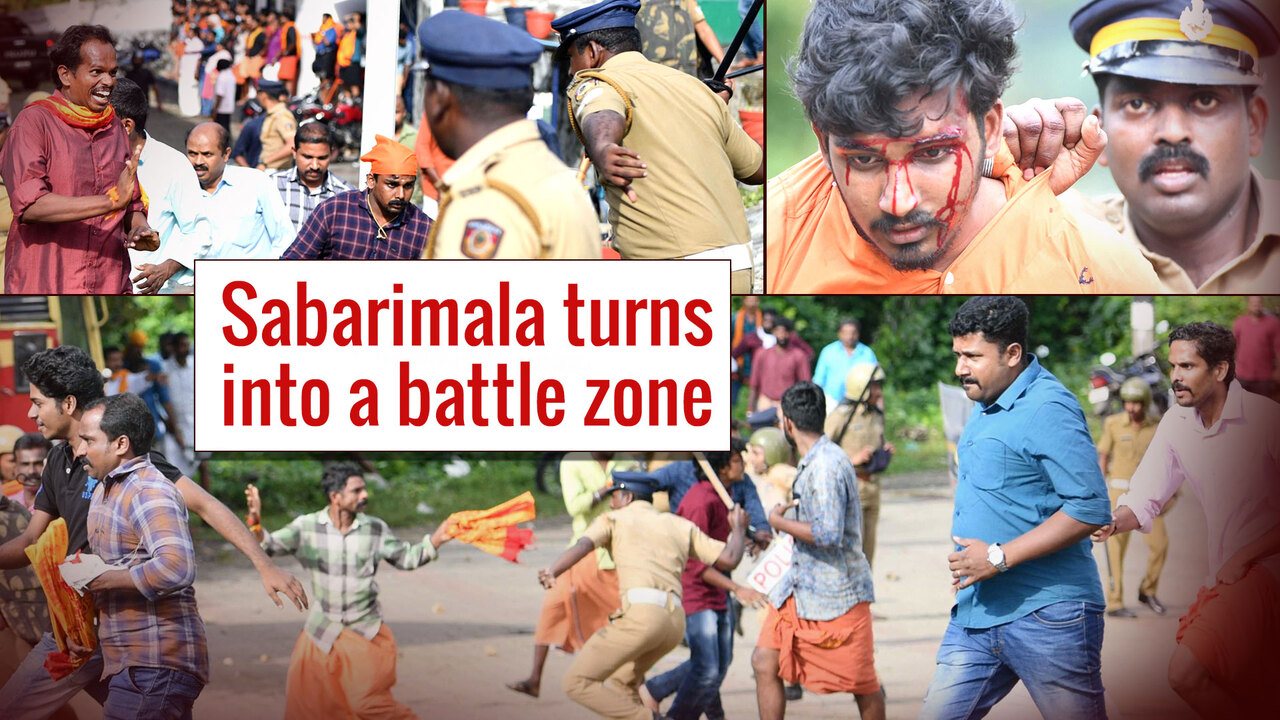

It was only a few hours ago, just before daybreak on October 23, that the senior male members of the erstwhile Pandalam royal family had returned to the palace from Sabarimala, some 80 km away. The hill shrine had closed the night before, after perhaps the most agonizing five days of monthly ritual pujas in the history of the temple.

The senior royals were now watching Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan's press conference live on a news channel in the living room of a modest single-storeyed concrete house that stood between the temple and the Srambical Palace where the box containing Ayyappa's 'thiruvabharanam' (royal ornaments) is kept.

The chief minister was combative. He was angry that the erstwhile royals had earlier said they had the right to shut down the temple. “Some claim to have certain rights over the temple on the basis of the 1949 covenant,” the chief minister told the press. “The Pandalam palace was not part of the covenant. They were so bankrupt that they had long before surrendered all that they had, including the income from Sabarimala, to the Travancore kings,” the chief minister said.

P N Narayana Varma, the secretary of Pandalam Palace Management Committee, laughed as if he had heard a joke. “It is no one's case that Pandalam palace was rich. But the transfer of properties was not a surrender as the chief minister is now making it out to be. It was done on friendly terms,” he said.

Kings on the run

Historically, the Pandalam royals were a highly subdued lot. Their forefathers were Pandya kings who had fled west from Madurai in the early 10th century fearing persecution by the powerful Cholas. When they finally settled in Pandalam, after trying out places like Harippad and Konni, they were only looking for a trouble-free existence. They brought under their sway 2000 sq km of largely uninhabited forested land. These kings were so meek that Pandalam was the sole local kingdom that the aggressive Travancore kings did not bother to annexe. But their independence came with a price.

Pandalam was asked to somehow find the money for Travancore's bloody and expensive battle with Tipu Sultan in 1790. They had to shell out a mighty, then unheard of, sum of over Rs 2.2 lakh, and soon enough went broke. From then on, Pandalam had no choice but to be fully dependent on Travancore for its daily existence. In return for lifelong support and protection, Pandalam transferred all the properties it had — including its biggest money-spinner, a non-descript seasonal temple on top of a hill called Sabarimala — to Travancore in 1820.

The Pandalam king as the father of the deity has given rise to one of the most important rituals of the Makaravilakku season: the 'Thiruvabharanam' (the royal jewellery) procession. King Raja Rajasekhara, who badly wanted Ayyappa to be his heir, is heartbroken when his son tells him that he wishes to take up a life of penance. Unable to bear his father's pain, Ayyappa grants him a wish. He can visit him every year at his forest abode, and see him the way he had desired.

So three days before Makaravilakku, when the brahminy kite (krishnaparunthu) hovers over the Pandalam palace, the king travels by foot along a rocky dense forest path up the hills to his son's abode carrying along with him, in a palanquin, a box filled with ornaments that he would have loved to see glittering on his son as he sat on the throne. Right down to this day, a member of the Pandalam royal family takes the 90-km three-day arduous trek up the hills with the royal ornaments in a palanquin. It is the difficult journey a father undertakes to get a glimpse of his beloved son.

Comic book kings

Historians have generally considered Pandalam royals insignificant. For instance, Manu S Pillai's highly regarded exhaustive work on Travancore, 'The Ivory Throne', has not a single mention of Pandalam or the Airoor Swaroopam, as Pandalam kingdom was known.

Pandalam royals belonged more in folktales than in history. Their only relevance seems to be their mythical, magical-realist, link to Lord Ayyappa. It is said that one of the earliest Pandalam kings, Raja Rajasekhara, who was hunting in the forest heard the faint but alluring jingle of a bell from inside the forest. He pierced deep into the jungle in search of the sound. As he parted the thick branches of a giant tree that blocked the sight of Pamba, he saw what he later told his childless wife was the most radiant sight he had ever seen. A haloed newborn, with a bell strung around his neck, cheerfully playing on the sand near the water. He adopted the child at the prompting of sage Parashurama and called him Manikantan, the bell-throated one.

Bell-throated one or Kandan's son?

The descendants of Mala Araya tribes who once lived in the 18 hills surrounding the forest rubbish this royal legend. They say Manikantan is a corruption of the original 'Manikandan'. “The boy was born to the childless Mala Araya couple Kandan and Karuthamma after they took a 41-day penance on the advice of the tribal priest Koorman. He was called Manikandan or Junior Kandan because he was Kandan's son, and not because he had a 'mani' (bell) around his neck,” said P K Sajeev, general secretary of Aikya Mala Araya Mahasabha.

He said the Christian missionary Samuel Mateer has written about Mala Araya civilisation in the areas around Sabarimala in 'Native Life in Travancore', published in 1833. “There are still evidence of Mala Araya civilisation in the hills near the shrine, for instance the remains of gravestones,” Sajeev said. “Even the 'pathinettampadi' concept evolved out of the 18 hills that surround the shrine,” he added.

Chronic bachelor

Curiously, even conflicting histories merge at certain junctions. It is said the Pandalam royals were on the run from the Chola kings. The Mala Araya tribes, too, were persecuted by the very same Cholas. “It was to defeat the Cholas that Manikandan took birth,” Sajeev said. The royal version also speaks of warrior Ayyappa, but in this narrative he is out to defeat the notorious brigand Udayanan and the terrifying beast-woman spectre of Mahishi.

The Mala Araya tribe, like the kings, believe that Ayyappa had studied 'kalari' in Cheerapanchira, near Alappuzha, and it was an Eezhava family that had taught him martial arts. Both the strands tell how the daughter of the 'kalari' guru, the beautiful Poonkudi, falls for the young Ayyappa and how he resists her romantic overtures.

In the royal version, it is said Ayyappa invoked his 'brahmachari' credentials. In the tribal telling, Ayyappa reveals another form of commitment. He convinces Poonkudi that his only objective in life was to fight for his 'gothra'. It is Poonkudi, many folklorists say, who has been installed near Ayyappa as Malikappurathamma. “Malikappurathamma is a motherly concept and not a romantic notion as is now being popularised,” said Thanthri Maheshwaruru of Thazhamon family.

Honey bath for Ayyappa

According to Mala Araya leader Sajeev, the rights of the tribals were taken away when the Thazhamon thanthri family began doing pujas in 1902. Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan, while asking the priests to behave, had mentioned that it were the tribals who had conducted 'thenabhishekam' (honey bath) on the deity. Thanthri Maheshwaruru said his family had been doing pujas in the shrine since 100 BC, and that he had not heard of the honey bath.

Narayana Varma of Pandalam palace had a slightly different take. “There was indeed the practice of bathing the idol in honey. But I don't think the Mala Araya tribesmen would have entered the sanctum sanctorum and did it themselves. Being honey gatherers they might have brought honey to the temple which the priest had used,” Varma said.

Nonetheless, he acknowledges the importance of tribals in the Ayyappa lore. “They were the ones who protected him during his exploits,” Varma said. It is also not disputed that it were the Mala Araya tribesmen who had once lit the 'makaravilakku' (the flame that lights up on the Ponnambalamedu hills on Makara Sankranthi day). It is also a fact that the tribes were evicted from the hills after the temple was reconsecrated following a major fire that gutted most of the shrine in 1950. Now, it is the KSEB employees who light the forest flame.

Noted historians like K N Purushothaman are disinclined to believe the thanthri's version that the Thazhamon family was in Sabarimala since 100 BC. Nonetheless, he qualifies the family as progressives. “They came into the picture late. Since it was deep inside the forest and filled with dangerous wild animals, no Brahmin priest was willing to take the risk to administer puja in the temple. But this family of priests, they being progressives, took up the task in the early 20th century,” Purushothaman said.

Man as God and vice versa

But the presence of a temple that precedes the birth of Christ is a possibility that many accept. All tales about Ayyappa has one common element: the Sastha phenomenon. The royal family, the priests, the tribes and even the historians say that Sabarimala was once a Sastha temple, one of the five that sage Parashurama had consecrated in various parts of southern Travancore. The indisputable belief is that the historical figure of Ayyappa merged with the spiritual idea of Sastha. That's why, perhaps, as a devotee climbs the last of the 18 steps the first thing he sees is the Sanskrit phrase 'Tat tvam asi' (thou art me). Man becomes God.

Each of these Sastha temples celebrate Ayyappa in different stages: Kulathupuzha (as a boy); Aryankavu (as a youth seated on an elephant with his lover Prabha); Achenkoil (as a householder with two wives, Pushkala and Poorna, by his side); Sabarimala (as naishtika brahmachari); and Kanthamala (as 'paramatma', in transcendent bliss). The Kanthamala Sastha temple is still a fiction, no one has ever recorded having seen the temple.