Agrarian distress: the plight of Maharashtra's onion farmers

Mail This Article

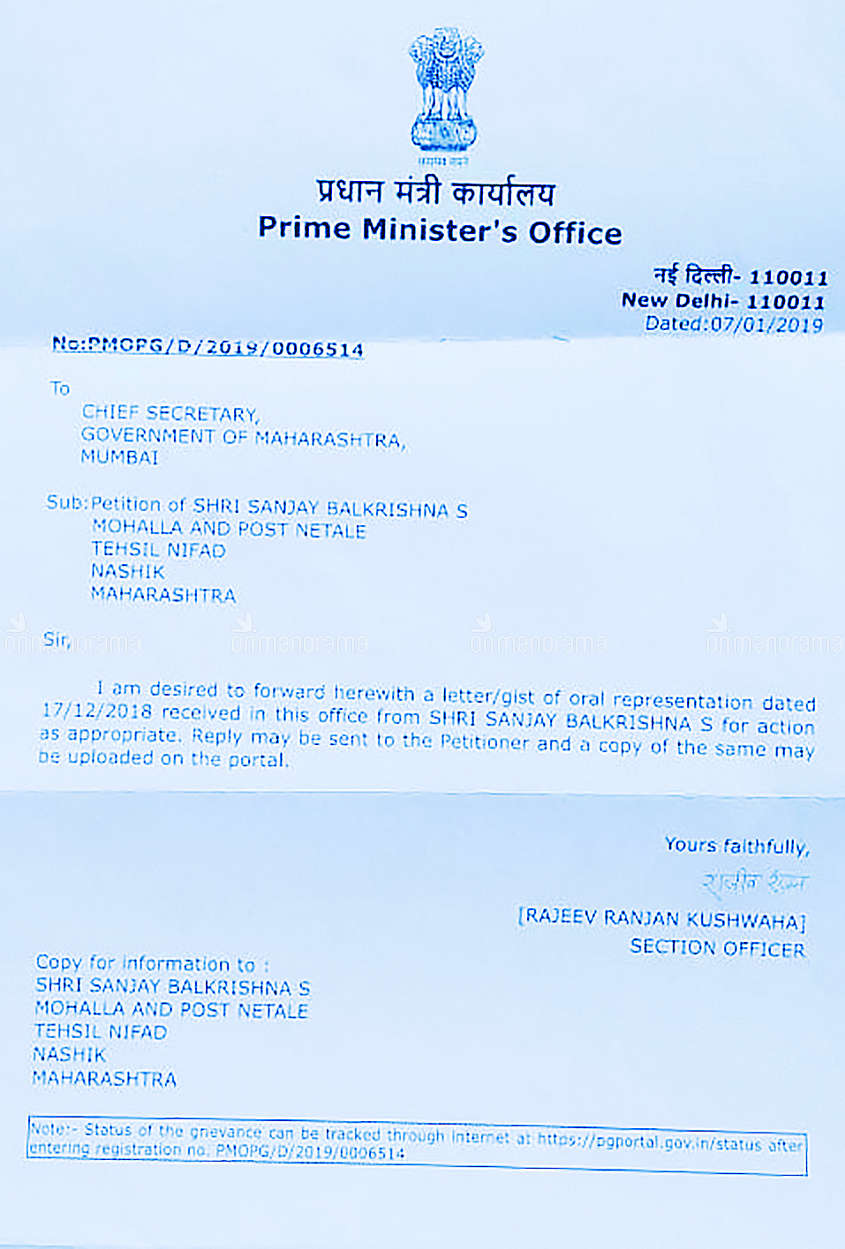

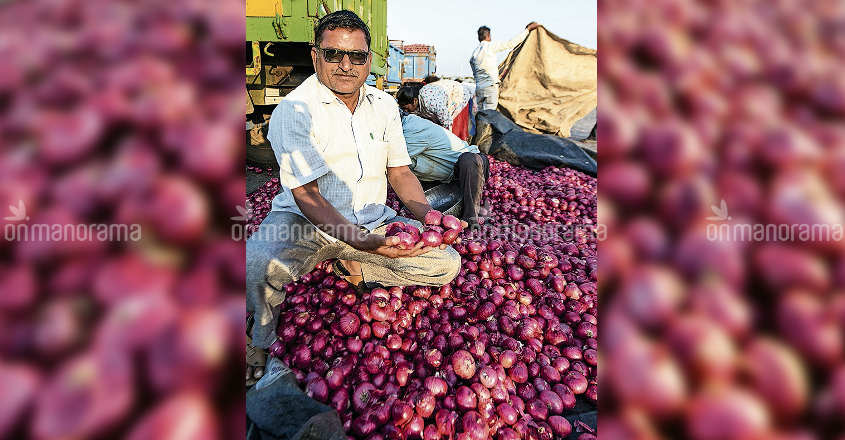

Last December, Sanjay Balakrishna Sathe, a grower based in Niphad taluka of Nashik district in north Maharashtra, hit the headlines when he sent his meagre earnings from sale of onions to Prime Minister Narendra Modi to highlight low returns.

The money order also carried this note: "I could earn a paltry Rs 1,064 after selling 750kg of onions. I’m donating the sum to the Disaster Relief Fund of the PMO (Prime Minister’s Office) through a money order to draw the PM's attention to the woes of farmers."

Sanjay had to pay additional Rs 54 for sending it by money order. Immediately, the PMO ordered Nashik deputy collector Sashikant Mangrule to look into the matter and file a report. Though the district authorities contacted Sanjay, the report mentioned that he got a lower price for his produce because the onions he brought to the market were 'substandard'.

Deeply hurt by the official apathy, he wrote a letter to the PMO in which he said the authorities prepared the report without conducting any inquiry and that it was 'false'.

"If a report submitted to the prime minister is fake, there is no hope left for the common man. Like the Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao scheme, I request you to initiate a campaign to save the country’s farmers," he said in his letter.

A few days later, the PMO replied to him and instructed the Maharashtra state chief secretary to submit a report at the earliest.

So, what prompted him to send his earnings to the Prime Minister? Let Sanjay explain. "I had harvested about 100 quintals in the summer, but because of the steep drop in the prices, I was forced to process and kept the produce. In June, onion was trading at Rs 800-900 per quintal in the local market. Though the price shot up to Rs 2,000 in the next few months, it had been on a downward trend since then.

I had no other option but to sell 750 kilograms from the stock as I was in urgent need of some money. On November 19, I went to the Niphad wholesale market with the produce but was offered a rate of Rs 1 per kg. Finally, I could negotiate a deal for Rs 1,064 for 750 kg. After making payment of labour charges of Rs 400 and transportation charges of Rs 700, I was left with just Rs 1,064. I could not even recover the costs incurred on taking the produce to the market, let alone cultivation expenses," he says, utterly dejected.

Interestingly, Sanjay was one of the 'progressive farmers' selected by the Union Agriculture Ministry for an interaction with then US president Barack Obama when he visited India in 2010.

Middlemen rule the roost

Sanjay is not alone as thousands of onion farmers in Nashik's Pimpalgaon region have found themselves in deep distress because of the steep drop in the prices of their produce.

Take the case of Madhukar Potte of Wadali village for example. He went to the wholesale market in Pimpalgaon, located about 60 kilometres away from his home town, with 20 quintals of onion. The auction started with a bid of Rs 200 per quintal and after negotiations for hours, the rate was fixed at Rs 300. As he had spent Rs 2,000 to transport the load to the market, taking it back was unthinkable.

Onion growers from faraway villages like Niphad, Chandwad, Bhatgaon, and Naitale too go to the Pimpalgaon market and sell at whatever price the trader is offering. They incur transportation and other charges that are more than the total price of the onions.

It is the middlemen who control the prices in markets across Nashik district, which accounts for nearly half the onion production in the country. It is no secret that they collude with each other to loot the hapless farmers by manipulating the auction. If there is less demand for onion, the farmers will not get the fair price for their produce. The day this reporter reached the Pimpalgaon market, the highest price quoted for a quintal of onion was Rs 500.

Efforts to make farming sustainable

The Central government has undertaken an ambitious task of doubling farmers’ income by 2022. The last time the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) conducted the Situation Assessment Survey of Farmers was in 2013. It had found that the average monthly income of an agriculture household was Rs 6,426. The government has constituted an eight-member inter-ministerial committee to prepare a blueprint for doubling farmers' income by taking 2015-16 as the base year.

As part of the initiative, the NSSO would conduct the 'Situation Assessment Survey of Farmers' this year. The mission would aim to double India's farm exports by focusing on developmental, technological and policy initiatives.

Effective implementation of the prime minister’s flagship programmes such as the irrigation scheme, Krishi Vikas Yojana, Soil Health Card, 'neem coat' urea production, Fasal Bima Yojana (crop insurance), food security scheme, and oilseed and horticulture development, would be decisive in achieving the target.

Challenges and solutions

High production of kitchen staples like onion, tomato and potato resulted in a glut in the market and the average wholesale price of these crops crashed. Farmers get a poor price for his produce, but the benefit of the price drop would not be passed on to consumers.

The biggest challenge for the growers is the available marketing options, which is grossly limited. Their goods have been traditionally sold in market yards dominated by middlemen, who buy the produce from farmers and further sell it to traders.

Essentially, by the time a consumer buys onions, it changes hands about four to five times. It's a long chain comprising farmers, traders, whole-sellers, mid-sized vendor and then the retailer. At every stage, there is added cost. When a customer purchases a bag of rice, the middlemen get a commission of about 48 per cent of the retail price. The commission is 52 per cent and 60 per cent for groundnut and potato respectively.

A robust system needed

Integrated farming is the best way forward to strengthen livelihoods of small and marginal farmers. It requires every beneficiary-farmer to cultivate various varieties of crops, besides taking up farm enterprises, for productivity improvement. Other than in Punjab, Haryana and parts of Uttar Pradesh, this method has not made much of an impact so far.

Large gaps in storage, cold chains and limited connectivity have added to the misery of growers. Due to the absence of adequate storage facilities and agri-logistics required to bring the produce from farm to markets, about 7 per cent of agricultural produce goes waste every year.

In Uttar Pradesh, 85 per cent of locally produced wheat and 90 per cent of oilseeds are sold in the local market itself due to lack of logistics connectivity.

Most of the farmers are reluctant to shift from traditional crops to other alternative crops. Their continued preoccupation with conventional way of farming only helps to bring down the prices.

The government should intervene and establish basic infrastructure to provide energy-efficient irrigation systems and power supply to the agriculture sector. Good scientific storage facilities need to be set up so that farmers can avoid distress sales. A system should be put in place to help farmers directly sell their produce to traders, eliminating middlemen. Also, the cluster model of cultivation needs to be promoted at the national level.

(To be continued…)

References: Major Agricultural Problems of India and their Possible Solutions by Krishi Jagran; Parliament Question & Answers.