Malayali muralist’s strokes on Banaras walls laced with music

Mail This Article

As Hindu families join Muharram processions in their Varanasi known for its historically strong secular fabric, Suresh K Nair walks along the Ganga that lines the holy city where he has been living for eleven years. The visual artist from down-country Kerala is himself heavily into such blend of cultures: he keeps sketching images to the audio backdrop of music.

It’s a curious variety of jugalbandi, which is usually a duet by two classical vocalists or instrumentalists. Suresh, with an ear for Hindustani notes, seldom misses an opportunity to translate his mental vibes into abstract pictures when Varanasi hosts concerts — aplenty, across seasons. Either as someone sitting in a quiet corner of the venue or as an invitee on stage along with the musician, the professor at Banaras Hindu University (BHU) scribbles his pen or brush animatedly. Morning, evening and night ragas that waft in slow pace across the famed ghats find quick representations in sketchbooks or the canvas.

This kind of an aesthetic pursuit has had its rudimentary beginning in Suresh when he used to attend traditional dance-dramas in his native state more than a quarter century ago. In countless venues of central Kerala during the early 1990s, the lean and bespectacled youngster was a familiar sight at Kathakali and Krishnanattam shows. Both the art-forms wooed Suresh to vintage temples and post-harvest paddy fields that hosted them in the deep nights of his native Palakkad district and neighbouring regions.

“Those were times when I was curious about finding ways to translate the movements on stage to paper. How the three-dimensional scenes can retain their vibrancy as drawings,” trails off Suresh, a native of Adakkputhur village near Cherpulassery. “That exploration took me, mainly to Kathakali performances, to places between, say, Kottakkal (in Malappuram district) and Kochi (Ernakulam district).”

The wanderings enjoyed little support from his family or even friends. “A majority of them took me for a madcap. Some, though, did suspect that I was into something seriously offbeat,” says Suresh, now 47. “Only very few thought my journey could be meaningful.”

That apart, Suresh had his share of joy in working amid the bustle of the Kathakali stage. “I remember how (iconic actor-dancer) Kalamandalam Ramankutty Nair would leap from the stool as Hanuman scaling the sea to reach Lanka (in the play Thoranayuddham). The dynamism in those two or three seconds would find representation on my sketchbook almost simultaneously with a handful of strokes with the pen,” he says. “On the flip side, some of the performers on stage found my presence discomfiting. For, some in the spectators, especially kids, used to get more eager to see my artwork shaping up than the story proceeding.”

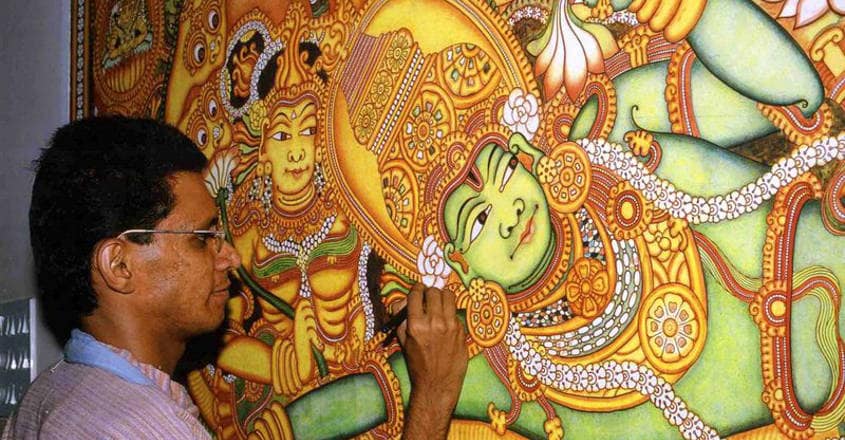

Besides Kathakali, Suresh tried similar experiments watching the lesser-known Krishnanattam, another traditional Kerala ballet. For that, he needn’t had to travel, because the venue was the famous Srikrishna temple in Guruvayur, where Suresh was a student at the mural painting institute. As a student of its first batch that got enrolled in 1989, Suresh would wait for the post-supper hour to be present inside the shrine where the Bhagavata stories would roll out to great music and percussion, with the mythological characters donning make-up and costume as colourful as Kathakali. “Those shows would go past midnight,” he recounts.

Murals weren’t Suresh’s first tryst with art education. Having completed schooling, he did a government-run two-year painting course from the Silpachithra College of Fine Arts at Pattambi, 20 km south of his house. “That did have my family’s backing,” he chuckles. “For, my neighbourhood school had a vacancy for an art teacher and my parents thought they could see me working there soon and leading a secure life.”

Suresh, instead, ended up doing advanced art studies from Bengal’s Visva-Bharati University and short-term courses in ceramic and terracotta murals in America and in film appreciation from Pune’s FTTI. All the same, he believes that the modest school in semi-hilly Adakkaputhur has played a big in moulding his basic aesthetics around which he continues to work. “The school had a good library that subscribed to serious Malayalam periodicals. They had illustrations by leading artistes of our times,” he notes. “Parallely, the choreographic boldness of Kathakali enticed me.”

That was how Suresh began drawing while watching the art. At one such venue, in Karalmanna not far from home, it was business as usual for the youngster at a Kathakali night when a foreigner woman noticed his sketching and got in touch with him. “It turned out she was a French woman, a puppeteer named Brigitte Rivelli,” reveals Suresh. “She was into a project on Kathakali mudras (hand gestures) and facial expressions. Brigitte wanted me to do some 700 drawings for her upcoming book on the subject.” Soon, Brigitte facilitated Suresh’s works making it to three exhibitions: in Thiruvananthapuram Delhi and Paris.

Soon after his five-year mural painting course in 1994, primarily under the venerated Mammiyoor Krishnankutty Nair, Suresh started getting assignments in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka to do frescoes. Amid all that, he got an offer to paint vignettes of the Sanskrit drama Abhinjana Shankuntanam at a leading gallery in Kochi. There, at the museum of the Madhavan Nayar Foundation, he got in touch with the works of Bengali painters yet again. “That rekindled my desire to study in Santiniketan,” he says. “It was something that was dormant inside me after having read an article in my school souvenir as a class-7 student. It was by (writer-activist hailing from Adakkaputhur) P T Bhaskara Panicker, who said great educational institutions can be modelled on the lines of Tagore’s university.”

While making moves to secure admission in Santiniketan, Suresh sensed the need to raise funds to meet the academic expenses. “I took a set of my paintings and went on a drive to sell them off in (the nearest town of) Cherplassery. Not many showed interest, but two hotels did eventually,” he says. “I mustered Rs 13,500, and soon took my train to Calcutta.”

The atmosphere at the 1921-founded Santiniketan, near Bolpur which is 180 km north of the West Bengal capital, filled Suresh with awe as much as excitement. Artworks of late titans such as Abanindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, Rashbehari Bose and Ramkinkar Baij sprang fresh energy. “So much so, I practically gave up my profile as a Kerala muralist,” he says, encapsulating the seven-year studies (bachelors and post-graduate) in Visva-Bharati University.

Even so, domestic compulsions brought Suresh back to Kerala, where he taught art at Sree Sankara University in Kalady of Ernakulam district for five years till 2007. Then, he left for north India, as the 1916-founded BHU recruited him in its department of painting under the faculty of visual arts.

Already familiar with the Hindustani music he heard abundantly at Santiniketan, a fresh wave of its notes overwhelmed Suresh in bustling Varanasi, 2,300 km away from his quiet village. At a concert by the Ganga in 2008, he impulsively drew as he listened to the music. That triggered a second round of carrying a sketchbook while going for a performing art — this time it wasn’t Kathakali, but Hindustani classical.

“It’s not just about the different in the two forms,” Suresh notes. “In the case of Kathakali, I was trying to reproduce its movement dynamics. So it had a relation with the story scenes, however abstract be the sketches. But with music, I seldom sketch the sight of the concert. I go by the sounds. It’s a transcendental experience. Often, I forget about my own existence.”

Suresh, all the same, has been into various art projects that trace subtler links with any performing art. For instance, his acrylic-on-canvas work Cosmic Butterfly (2013) has some of the 750 images of the beautiful insect bearing elements from Kathakali faces. Far departed from that, Suresh is also into public art that seeks to beautify Varanasi by making its hitherto unattended spots aesthetically pleasing through public participation.

“Turning shabby walls and garbage dump-sites into places sporting vibrant wall murals is a happy challenge,” he says. After all, Varanasi has joined the global bandwagon of Unesco’s ‘Cities of Music’ project that seeks to revive the ancient city’s culture which also celebrates Hindu-Muslim brotherhood.