‘Malabar rebellion not a Jihad’: Interview with US historian Stephen Dale | Watch Video

Mail This Article

Note: This interview was first published on July 12, 2020.

US historian Stephen F Dale, professor emeritus at the Ohio State University, has asserted that Malabar rebellion of 1921 was not a Jihad, or a holy war.

Dale, who researched on the rebellion in the 1970s and authored a seminal book on the topic - Islamic Society on the South Asian Frontier: The Mappilas of Malabar 1498 - 1922 (Clarendon Press,1980), said the rebellion had never shown the characteristics of Jihad. “The attacks by Mappilas were directed against the offices and soldiers of the British government. There were not really attempts forcibly convert Hindus to Islam, except one or two cases,” he said in a special interview with Onmanorama from the US.

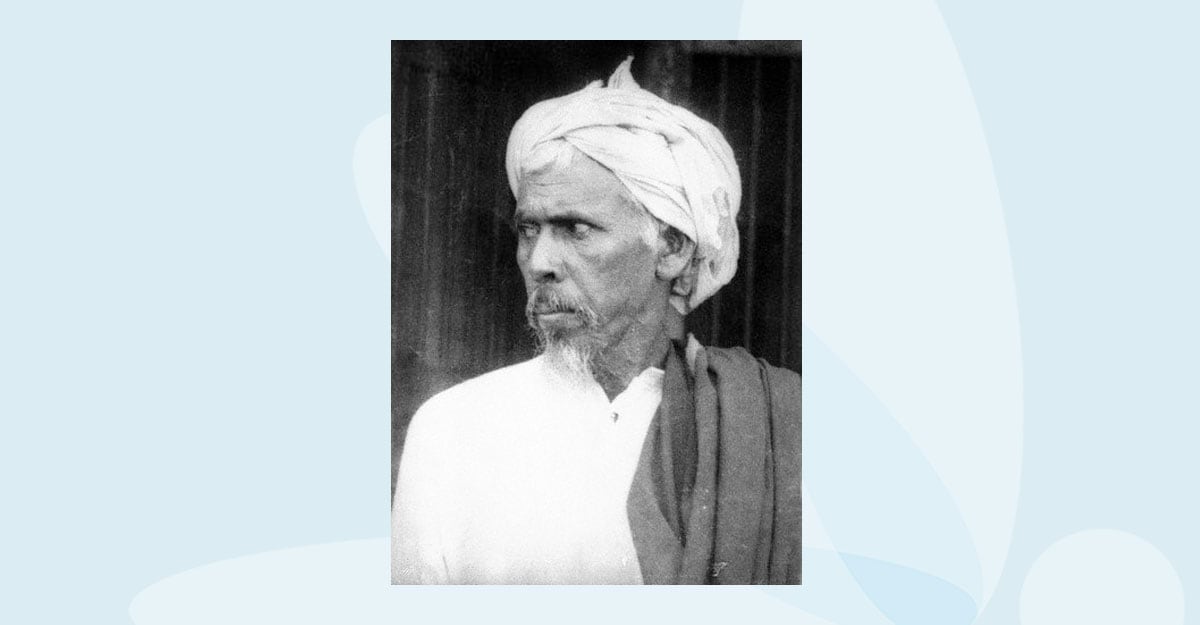

He said many might have termed the rebellion a Jihad because some of its leaders, such Variyankunnathu Kunjahammed Haji, had plans to establish a Muslim government. “It is really a mistake to term the rebellion as Jihad. All those who participated in the rebellion had staunch anti-British stand,” he said.

This interview was conducted against the backdrop of the debates in Kerala after film director Aashiq Abu announced a movie on Variyankunnathu Kunjahammed Haji. Right-wing Hindutva organisations had termed the movie - titled Variyankunnan - as an attempt to ‘glorify the attack against Hindus’ and urged the project’s designated lead actor Prithviraj to sever his ties with it.

Edited excerpts from the interview:

Broadly, we have two different perspectives on Malabar rebellion. First one is the colonial and Hindu right-wing perspective (which considers the rebellion as attacks carried out by Muslim fanatics against Hindus) and the nationalist and Marxist narrative (which portrays the rebellion as a fight against imperialism). What do you think about these narratives? Which one do you subscribe to?

I would not accept either of those two arguments completely because the Mappila rebellion was a very complex and unplanned phenomenon, stimulated by the Khilafat movement.

Some the leaders of the rebellion - such as Variyankunnathu Kunhahammed Haji - had the political idea of establishing a Muslim government in Ernadu and Valluvanadu taluks in Malabar. But they were guided by strong anti-British feelings, which were evident from the attacks on the institutions and soldiers of the British government.

Obviously, there were long-term tensions between the Janmi (landlord) class and the poor tenant farmers belonging to both Hindu and Muslim communities. While Mappila tenants had an ideology to justify their resistance, the Hindu tenants did not.

Thirty-three Mappila outbreaks were recorded between 1836 and 1919 in South Malabar. The most identifiable characteristic of the outbreaks was the suicide of Mappilas who had participated in the attacks. Of the 350 directly involved in attacks, 322 committed suicide and only 28 survived to be captured. Those who died were considered as Shahids or martyrs. How do you view those ritualised form of suicide?

Mappilas had a long history of hailing martyrdom. For example, I had seen, during my research in the 1970s, offering boxes for the martyrs of the Arab battle of Badr in Kerala.

In the case of Mappila outbreaks, those attackers of the British and landlords knew that they would be captured and executed. The alternative for them was to die as a respectable man or attain martyrdom within the context of Islam, instead of being killed by Europeans.

This form of suicides could be found in other parts of Asia, such as Aceh in Indonesia and Philippines. Is it possible to establish any connection among these incidents?

Many Keralites went back and forth to these areas. Members of the Mappila community in Kerala had connections with Indonesia and Yemen. But the main reason for the suicides was the assault on Muslim trading community by the Europeans.

Attempts have been made to portray the Mappila attacks and suicides as Jihad or holy war. How do you view such readings?

It is a mistake to term the rebellion as Jihad. All those who participated in the rebellion had staunch anti-British stand. Those attacks were directed against the offices and soldiers of the British government. There were not really attempts forcibly convert Hindus to Islam, except one or two cases. Many might have interpreted the rebellion as Jihad because of the plans of its leaders, such Variyankunnathu Kunjahammed Haji, to establish a Muslim government.

Everybody terms the 1921 incident as the Mappila Rebellion. However, only one-third of the Muslims from three South Malabar Taluks participated in it. Rich Muslims did not endorse it. Salafi movements did not support it. It was not a pan-Islamist movement. But it had seen the participation of Hindus. Then how did the name - Mappila Rebellion – get acceptance in the society?

Most of the people who took part in the rebellion were Mappilas. British were quite paranoid about Muslim political activity after the 1857 mutiny and some of the events in the Bengal in the 19th century. I think it is legitimate to call it the Mappila rebellion because most of those who fought against British were Mappilas.

Why were those outrages and Malabar rebellion confined to three Taluks in south of Malabar especially when the north Malabar districts too had many Muslim strongholds?

That is a really difficult question to answer. I think it had to do primarily with individual leadership because leaders like Variyankunnathu Haji were from South Malabar.

The Malabar Rebellion was largely ignored in other parts of India. Officially 2,337 people were killed and 1,652 wounded and 45,404 were imprisoned in the incident. (Unofficially, the death count was 10,000). However, it did not get prominence like the Jallian wala Bagh massacre of 1919 in which 379 people were killed or the Chauri Chaura incident of 1922 in which 23 policemen were burnt alive by angry peasants. Why did this happen?

The Khilafat and non-cooperation movements were essentially non-violent and those associated with them were appalled by the Malabar rebellion. I think they did not want to publicise such things. Even the British themselves did not want to publicise the incident.