On Sree Narayana Guru’s birthday, Fraternity as the motif for our times

Mail This Article

It was independent India’s first Law Minister and Chairman of our Constitution’s Drafting Committee, B R Ambedkar, who was instrumental in making the French Revolution’s motto of “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity” part of the preamble to the Constitution of India. But he clarified subsequently that he did not borrow the basis for his social philosophy from the Revolution.

In an address over All India Radio in 1954, Ambedkar had said unambiguously that: “My philosophy has roots in religion and not in political science. I have derived them from the teachings of my Master, the Buddha. In his philosophy, liberty and equality had a place; but he added that unlimited liberty destroyed equality, and absolute equality left no room for liberty…He gave the highest place to fraternity as the only real safeguard against the denial of liberty or equality – fraternity which was another name for brotherhood or humanity, which was again another name for religion."

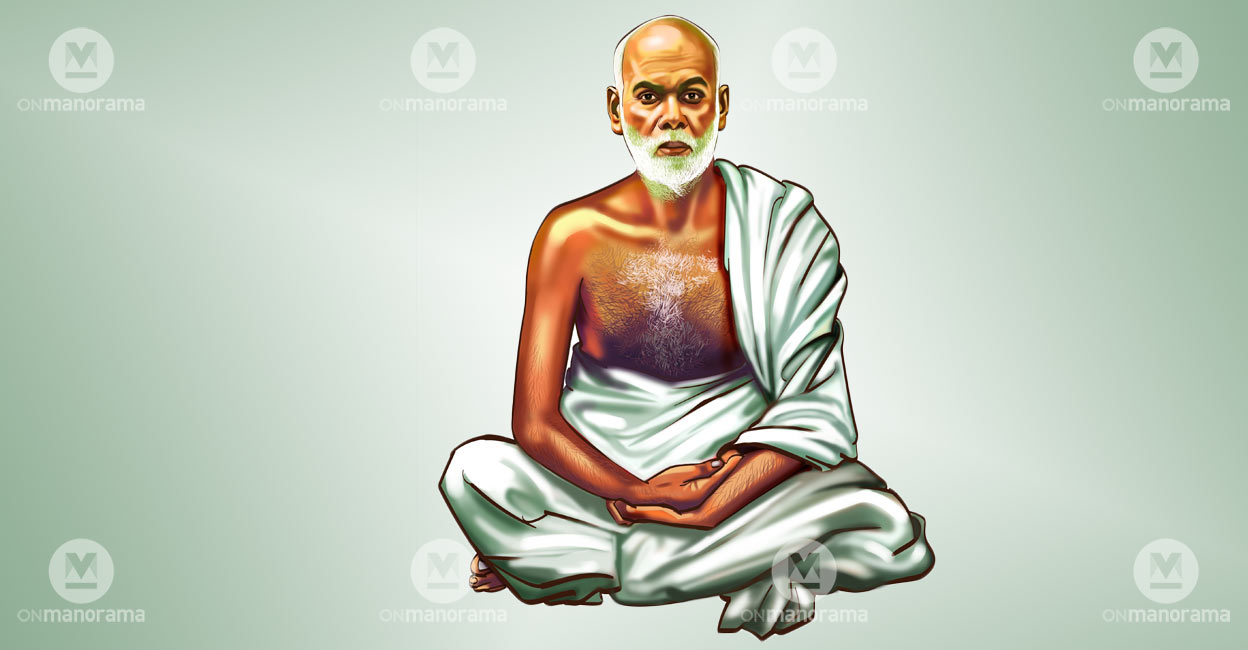

Fraternity as religion is also the summum bonum of the approach of Sree Narayana Guru, another reformer who built his philosophy on the foundation of his own personal experiences as one born in a so-called backward caste, taking into account the objective reality of the social and economic conditions of society around him. As we commemorate his birthday today, there is a compelling need to revisit and reimbibe his iterations of religion because the world over, there is a tendency to stretch their boundaries to create conflicting and discordant situations.

The Guru fashioned his theme on the platform of the oft-repeated vision of “One caste, One creed, One Religion for humankind”. It was predicated firmly inside religion, not outside of it. Though he had followers like Sahodaran Ayyappan and CV Kunhiraman, with avowed atheistic lines of thinking, the Guru was firmly embedded in the Advaitic (non-dualistic) tradition of Adi Sankara, another great philosopher who was born in (now) Kerala and is unanimously acknowledged as the most logical/coherent of India’s spiritual masters.

Unabashed in his practical advocacy of the “continuity” of this tradition, numerous are the temples that the Guru built and consecrated. He established the Advaita Ashrama at Aluva and a Sanskrit school was attached to it. His style of reformation was not agitprop. Though he followed the “path of least resistance”, to use a folk-physics term, there was unprecedented kinetic energy in the movement that he spearheaded for reform, the ripples of which are felt even now.

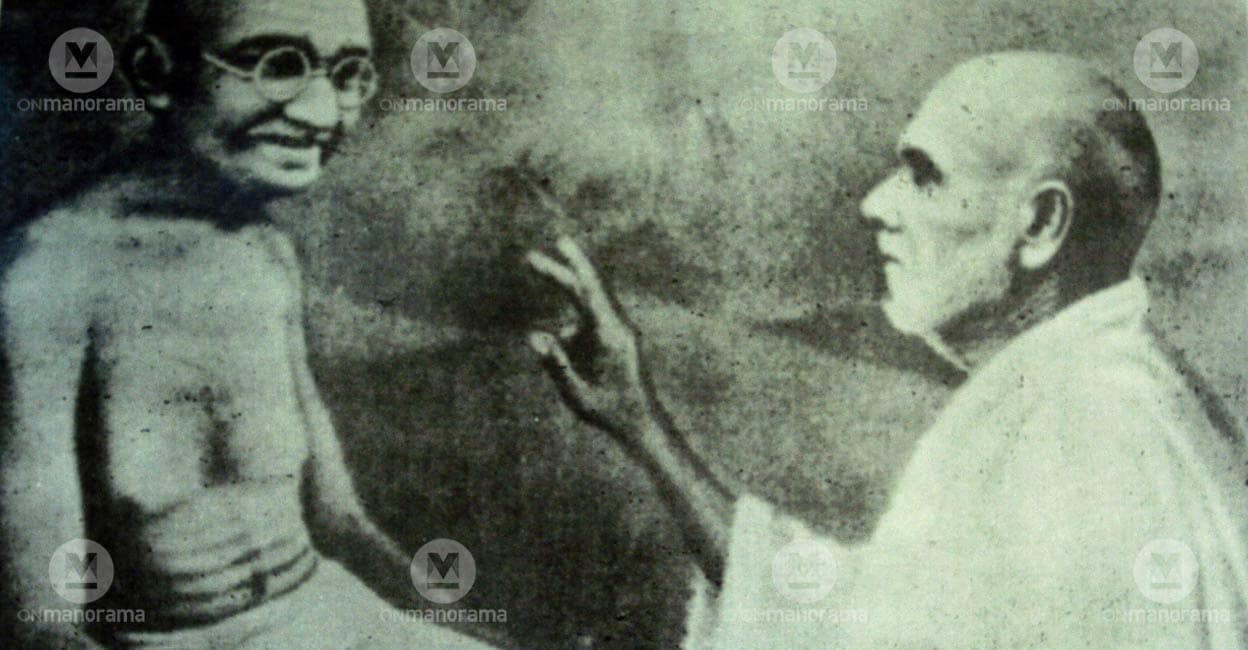

Perhaps, he was to Kerala what Gandhiji was to India, as both understood the texture and the context of the milieu in which they were operating and developed indigenous and endemic solutions to the problems of their times.

The Guru’s approach is of utmost relevance in Kerala, the most religiously diverse State in India with 55% Hindus, 26% Muslims and over 18% Christians, not to forget the many who practise numerically minor religions. In economic and social development, there is the famed “Kerala Model” which is touted as different from the paths followed by other States of the Union.

While this economic “Model” is open to criticism, there is universal acclaim for the ability of numerically large religious groups in Kerala to rub shoulders with one another without upsetting the apple-cart of peaceful coexistence. The Guru’s birthday coincidentally follows Kerala’s cosmopolitan festival of Onam, which despite its Hindu mythological origins is celebrated by families across the State. The same goes for Christmas and Eid, when people exchange greetings respecting the heterogeneity of religious practices, even as they acknowledge the homogeneity of society at large.

In the wake of current international developments like the triumph of the Taliban in Afghanistan, extremist upsurges and the increasing radicalisation of religions, it is important to remember the “indivisibility” of humankind that the Guru propounded. Samuel Huntington’s hypothesis of the “Clash of Civilizations” written about three decades ago seem to be acquiring ominous overtones of reality as the G-7 debates how to deal with the Talibanisation of parts of Asia.

Even as the Church has seen dwindling numbers among Sunday worshippers in large parts of Europe and the UK, faultlines on the basis of ethnic/religious identities are also increasingly being felt across the world and in Europe too. If religions are going to be a present and pervasive influences, it would then be necessary to highlight their unifying strands as negating them would be of no avail and may even be counter-productive.

Swami Vivekananda’s prophetic words at the final session of the Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893, hence bear repetition: “If anybody dreams of the exclusive survival of his own religion and the destruction of the others, I pity him from the bottom of my heart…Upon the banner of every religion will soon be written, in spite of resistance:’Help and not fight’, ‘Assimilation and not Destruction’, ‘Harmony and Peace and not Dissension’.”

In many ways, the Guru’s principles were coterminous with that of Swami Vivekananda too. In his introduction to the authoritative biography of the Guru by Prof M.K. Sahoo, the late Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer wrote: “The taciturn wonder of Sree Narayana Guru’s impact on the human community is almost comparable to the thunderous oratory of Vivekananda”. The Guru’s chiselled language and stillness, woven around the motif of “fraternity”, is indeed the most eloquent guide to India’s journey onward.

(S Adikesavan is Chief General Manager in State Bank of India, working out of Thiruvananthapuram . Views are personal.)