Why ESZ satellite survey is causing discontent along Kerala's forest fringes

Mail This Article

The preliminary report of the satellite survey, carried out to identify the man-made structures within the proposed 1-km ecologically sensitive zones (ESZs) around the 22 protected areas in Kerala, seems to have generated widespread confusion and anger.

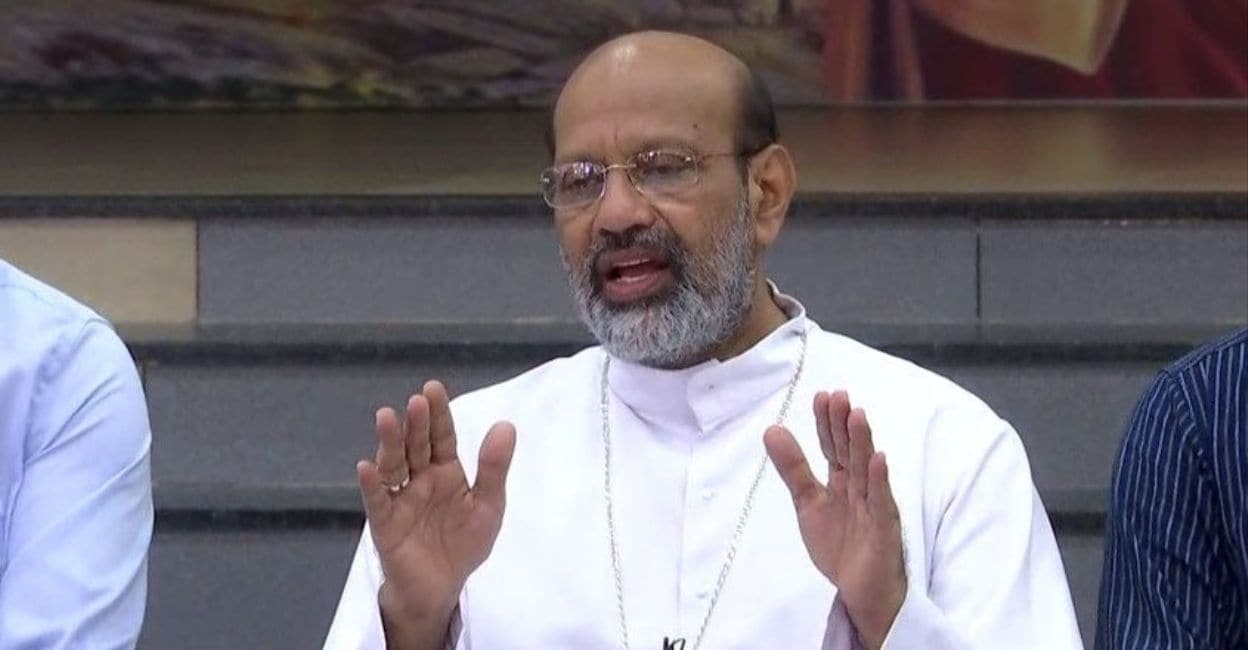

Like in 2013, when a major revolt was mounted against the Madhav Gadgil report, the Kerala Catholic Bishops Council (KCBC) is once again in the vanguard of a swiftly gathering public resistance against the government.

The KCBC has already called for the withdrawal of the maps produced by the satellite survey.

The Church has also backed the protests launched by farmer outfits like Kerala Independent Farmers Association (KIFA) and Infam (Indian Farmers' Movement).

What's wrong with satellite survey?

The survey, conducted by Kerala State Remote Sensing and Environment Centre (KSREC), has identified 49,324 structures (houses, schools, hospitals, offices, places of worship, commercial buildings and tribal settlements) in 115 villages around the protected areas.

The criticism is, the survey has missed considerably more than it has included. It is said the actual number of structures within the proposed ESZs would be upwards of 2 lakh.

The KCBC and farmers' organisations say that the satellites had failed to spot small structures of the poor -- especially thatched houses, small shops and those little buildings under the cover of trees.

Roads, water bodies and other landmarks that would give people a better understanding of the spread of the proposed ESZs have also not been included in the maps.

Even the CPM-led Sulthan Bathery Municipality had passed a resolution urging the government to carry out a thorough ground-level verification so that a complete list of structures within the ESZs could be drawn up.

The preliminary list seemed so sparse that only 14 of hundreds of shops in Sulthan Bathery town have found a place in the map.

It was also felt that the deadline (December 23) set for the public to provide details of the missing structures was too inadequate; the maps were published on the official website only on December 13.

Forest minister A K Saseendran, too, has eventually conceded that there could be defects in the aerial survey.

He assured that the report would not be submitted in the Supreme Court when the case would come up for hearing on January 11, 2023, hinting that a new report would be drawn up after ground verification involving other departments like Revenue and Local Self Government.

What led to the survey?

It was a Supreme Court order on June 3 this year, which said that every protected area in the country should have an ESZ of at least 1 km, that necessitated such a survey.

The order marked the culmination of two reports filed by the Central Empowered Committee (CEC) set up by the Supreme Court in 2002, one in November 2003 and the second in September 2012.

The 2003 report was specific to one protected area. It detailed the horrific manner in which Rajasthan's Jamwa Ramgarh Wildlife Sanctuary was being ravaged by mining activity.

Soon it became evident that mining was degrading forests across the country, not just in Jamwa Ramgarh. The 2012 CEC report, after taking into account the fast spreading menace of mining, pitched for ESZs for all protected forests in the country.

By then, in 2011, the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) had published guidelines for the declaration of ESZs.

The June 3, 2022, order, which draws inspiration from the 2012 CEC report and ratified the 2011 MOEF&CC guidelines, directed the states to quickly draw up a list of what it termed "subsistence structures" within the 1-km stretch surrounding PAs.

It wanted the list submitted within three months, before September 3.

Was SC adamant about ESZ?

The June 3 order of the SC was notable for its empathy. The court was open to relax even the minimum requirement of 1 km for the ESZ.

Here is what the order said: "The minimum width of the ESZ may be diluted in overwhelming public interest but for that purpose the state or Union Territory concerned shall approach the CEC and MoEF&CC and both these bodies shall give their respective opinions/recommendations before this court. On that basis, this court shall pass an appropriate order."

On December 1, the apex court further underscored the need to be sensitive even while battling to protect forests.

Justice B R Gavai, while hearing a batch of applications seeking exemption from the June 3 order, had this to say: "While passing orders, some ground realities have also to be taken into consideration."

He gave the example of a large patch of forest along the road from Jaipur to the Jaipur International Airport in Rajasthan. "If in such places, the ESZ is accepted, then the entire road will have to be demolished or converted into forests. Then there will be no connectivity for the city", Justice Gavai said.

The Supreme Court has clearly demonstrated its willingness to listen to public grievances. It is up to Kerala to convince the court of the impact of the proposed ESZs on human lives along the forest fringes.

Why were field inspections put off?

In fact, KSREC had completed the satellite survey in a month, by mid July.

The shortcomings were evident right then but an expert Committee to clean up the preliminary report (under Justice Thottathil B Radhakrishnan) was formed only on September 28.

Strangely, when this five-member expert committee published the maps on the official government website two-and-a-half months later, on December 13, not a single change was made to the KSREC report.

An inside source attributed this failing to the committee's preoccupation with the development of a software that could quickly incorporate the findings of the ground-level verification.

But it is also true that the Justice Thottathil Radhakrishnan Committee had plans to carry out field-level inspections in the proposed ESZs but had abandoned the plan before it even started.

There was official information that the committee was about to begin ground truthing around Neyyar and Peppara wildlife sanctuaries in Thiruvananthapuram district in the second week of November.

The exercise did not take off fearing public displeasure.

A draft notification issued by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) in late March this year declaring 70.906 sq km of non-forest areas as ESZ had already caused widespread resentment in areas like Amboori, Kallikkad and Kuttichal.

"To visit these very panchayats for ground verification would have once again inflamed local fears about ESZs," the source said.

However, Joy Elamon, the director general of Kerala Institute of Local Administration and a technical member of the committee, said field inspections were put off for what he thinks was a smarter reason.

"We realised it would be better to do the ground verification after securing inputs from the people. Or else we would have had to conduct two field inspections," he told Onmanorama.

Was SC order based on LDF notification?

The Congress has repeatedly alleged that a notification issued by the LDF government in October 2019 was one of the inspirations behind the Supreme Court's insistence on a minimum ESZ of 1 km.

The Congress leaders base their argument on a statement made by then environment minister Prakash Javadekar in Parliament in 2021 that the declaration of ESZs were based on the recommendations made by state governments. The 2019 notification had proposed ESZs with a width of 0-1 km, but it said even human habitations could be included within the ESZs. This approach, seemingly placing conservation above people, was prompted by the massive 2018 floods.

The 2019 notification had superseded a 2015 one issued during the UDF period. The UDF notification, issued on the basis of a 2013 MoEF order fixing a 10-km width for ESZs, had exempted all human habitations from the ESZ.

The Congress charge is, the LDF government had diluted the original pro-people policy of the Kerala government.

After this year's June 3 order, and following strident criticism, the LDF government had revised its position saying all human habitations should be exempted. Nonetheless, it has still not withdrawn the 2019 notification.

Law minister P Rajeeve said to project the 2019 notification as going against the interests of the people was an attempt to mislead. He argued that the 2019 notification did not specify 1 km but said 0-1 km. "The '0 km' clause was included to avoid human habitations," he said, and added: "After we issued the notification, the public was heard and our recommendations were revised to exempt all human habitations," the minister said.

He also did not feel the need to withdraw the 2019 notification. "Why repeal it when the '0 km' clause is part of the 2019 notification. We have filed the review petition in the Supreme Court acting within the 2019 order," Rajeeve said.

What are prohibited in ESZ?

The concept of ESZs emphasises regulation over prohibition.

Within an ESZ, human activities will be divided into three: prohibited, restricted with safeguards and permissible. Of around 30 major human interventions only eight are prohibited. The rest are either allowed with safeguards or permitted.

The prohibited activities are: commercial mining (not mining for personal purposes like digging the earth to construct houses or for the manufacture of tile or bricks), setting of saw mills, setting up polluting industries, commercial use of firewood (applicable only for hotels and other business establishments, not houses), major hydroelectric projects, tourism using aircraft or hot-air balloons, use or production of hazardous substances, and discharge of effluents and solid waste in water bodies and nearby areas.

Even widening of roads or groundwater harvesting or felling of trees are allowed, but with safeguards.

No permission is required to carry out agriculture activities or to adopt renewable energy sources or for rainwater harvesting or to even construct or repair houses.