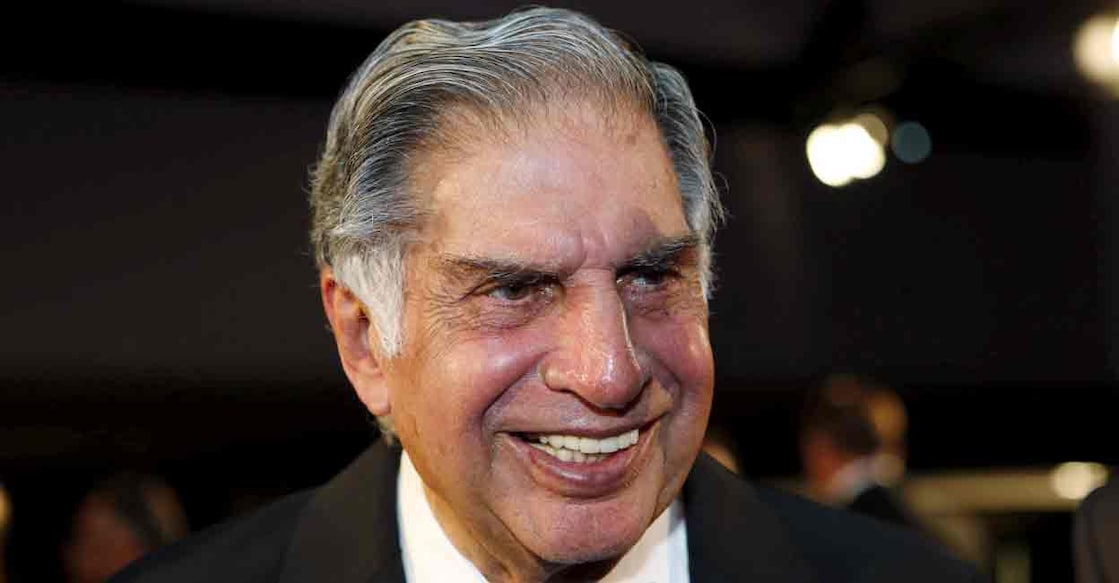

One and only Ratan

Mail This Article

Ratan Tata, the titan, has passed on. Though he led a full life, his departure will nevertheless leave a void in the nation and many parts and organisations worldwide. This void can never be filled as he was a man like no other. He combined a dizzying array of talents, subordinating his business interests to social goals, making him unique among businessmen. For me, it is an unfathomable loss.

I do not think there would be any Indian who would not have heard about him. But the details of his enormous contributions are less known as he was loath to talk about his achievements—he was a kind of shrinking violet and also an intensely private person who shut off the world from his personal life. Both are, however, at once amusing, interesting, and exceptionally inspirational.

Unlike what most people believe, his life’s journey has not been one of roses. It was both traumatic and challenging. Though in his earlier years, he stayed like a prince in the opulent Tata House, inspired by a mansion in the Champs-Élysées area of Paris, and the Petit Trianon, a neoclassical château built in the eighteenth century on the grounds of the Palace of Versailles, with columns imported from Italy and models in plaster of Paris shipped from France for approval, his fairy tale life was short-lived.

His father was adopted from an orphanage, according to Prasi customs, to serve as a son to Lady (Navajbai) Tata, the widowed wife of the second son of Jamsetji Tata, Sir Ratan Tata, as they had no children. Ratan was abandoned by his mother when he was only around seven years of age. His parents' divorce in the 1940s, which was a rarity then, led to the social shaming of Ratan and his brother Jimmy in school, adding to the trauma the children faced because of the difficulty his father faced as his wife had walked out on him and subsequently married Sir Jeejeebhoy, who she was seeing.

During this turbulent period, his grandmother, Lady Tata, took him under her wings, protected him and gave him stability. She was his benefactor extraordinaire and the person who moulded his character. She was a lady of high ethical standards, and this is what she taught Ratan and demanded the same from him—the principles that Ratan never abandoned in his life.

Ratan, too, was strong, and he did not let the trying circumstances crowd him down. He did well in school and left for the US for higher education. In choosing the subject and the place to study, he overcame his father's opposition, who wanted him to go to England and pursue accountancy like him and return to India by getting his grandmother to weigh in on his side. Ratan’s heart was lost to architecture, but as a compromise, he took mechanical engineering at Cornell. But he later shifted to architecture, in which he distinguished himself. It led him to be offered a dream job with a bespoke firm in Los Angeles, where he fell in love with the daughter of one of the firm's partners who employed him.

He wanted to marry her, but he had to come back because his mother was ailing. She was to follow him, but the war between India and China in 1962 persuaded her not to come to India. Finally, she married a man very similar to Ratan. But their romance did not end there. On her husband’s death, the embers of their romance, which had never died, were rekindled, and she visited India frequently, staying with Ratan at his house. And it was an interesting experience for me to interview her in San Francisco for the biography of Ratan.

Apprentice trainee

On his return to India in 1962, JRD Tata chose him to begin work from the shop floors of TELCO, now Tata Motors, and TISCO, now Tata Steel. He trained like an ordinary apprentice, was a keen learner, and treated everyone with deep respect. The two years of mechanical engineering course that he did helped him contribute significantly to several changes that were made in TISCO on the basis of his recommendations.

After he returned to Bombay in 1968, he was given several assignments. But the first major responsibility was his appointment in 1981 as chairman of Tata Industries Limited (TIL), a promoter company. During his chairmanship of TIL, he authored the famous 1983 strategic plan that became the blueprint for the growth of Tata Companies. He emphasised the group's coherence and building collective spirit among companies led by the stalwarts but operating in their own separate spheres and with their own goals. His second major appointment was as Chairman of Tata Motors in 1988.

In early 1990, he updated the strategic plan with the earlier one. These two plans helped him lay down a blueprint for the Tata Group companies to meet the challenges of economic liberalization and seize the opportunities it offered. Soon, they began what would become the largest reorganization in India’s corporate history.

A highly patriotic man, he was driven by the need to fulfil social goals rather than business aims. For Ratan, most business opportunities originated from social demands. It is all about fulfilling and sustaining a social goal through a business enterprise. The products of Nano and Swach can be considered examples of his endeavour. In the former, he aimed to make the roads safer for common people, and in the latter, he aimed to provide safety to the common people in their homes from deadly water-borne diseases.

While talking to me about Ratan, Henry Kissinger, the doyen of international politics, said that Ratan would qualify to be categorised among the top two per cent of the world’s businessmen. He attributes this to the fact that Ratan is ‘concerned not only with profits’ but also the need to make a ‘contribution to society’.

Through his major overseas acquisitions, Tetley Tea, Jaguar Land Rover and Corus steel, Ratan, in what he called was in an act tantamount to a ‘kind of the empire striking back’, hit the bastions of the western redoubts—becoming the employees or subjects of what the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, contemptuously had termed as the ‘beastly people’. He also reminded them that English mornings depended on the three Ts for cheer.

What distinguished him from other industrialists was his humility and empathy. A close associate of Ratan said there was no change in his attitude towards people even after he became chairman. He remained the same and treated everyone equally and respectfully. Ratan’s empathy has always been exemplary. Even during his tenure at NELCO, when he was facing workers’ unrest during the lockout, his constant refrain was, ‘How will they support themselves? We locked them out.’

Kadaknath chicken eggs and gooseberry arishtam

I have known him for the last three decades, and perhaps there is none with whom he has shared so many stories of his personal and professional life as he has done with me. He kept virtually no secrets that much of what he shared will have to be interred with me.

But our relationship was most interesting for the wide spectrum it covered. It spanned the personal to the professional, and I was an inalienable part of both. I loved and respected him so much that I did not even consider it necessary to think twice or even check with him before I did anything concerning him. If I found that it was good for him or it was something he liked, I just did it.

Some years back, when I found him getting weak and learned that he had stopped eating breakfast, I insisted that he eat Kadaknath chicken eggs that I began sending regularly from my farm near Delhi. It continued for over three years until his health improved dramatically. When I found that he was getting frequent colds, I began sending him our own gooseberry 'arishtam', made at home with all the spices. Though he was initially reluctant, he began having it, and it worked wonders for his immunity.

Love for mangoes

But most hilarious was his child like fascination for mangoes. Every season, I sent him over three dozen varieties of the tastiest mangoes that I grow in my farm as a hobby (of the Kerala varieties, he liked Kolomb and Priyur the most), for a change from the Alphonsos that he normally ate in Mumbai. One season, when it did not reach him as usual, he called up my help (my office had shared the number with him) on the farm and inquired why he was late in sending him the mangoes. Later, my help, not knowing who he had spoken to, casually informed me that a certain Tata had called from Mumbai and asked why mangoes were not sent for him while thanking him profusely for sending him the mangoes every year. That was his humility and the respect he gave every individual.

On the professional side, we were closest during the Cyrus Mistry crisis. He was then torn and extremely perturbed that he had to take to replace him in a manner he said was not the Tata way, meaning walking him to the door in a dignified manner. There was hardly any week when I did not meet him, share my thoughts on the case, and prepare briefings for his meetings with his lawyers. By the time he stepped down as chairman of Tata Sons in 2012, he had taken the topline growth to unprecedented levels.

Ratan the leader

During the almost 21 years he was chairman of Tata Sons, the turnover of the Tata companies crossed over 1,740 per cent. More interestingly, 60 per cent of these revenues came from overseas.

He achieved this through an elaborate, granular restructuring programme. This programme brought cohesiveness to the group and made it a tight organisation. Most importantly, he did it by increasing the stake of Tata Sons, the promoter of its companies. In 1991, when he took over as chairman, the shares of Tata Sons in its companies were perilously low, making it vulnerable to takeovers.

Ratan increased his stakes in the Tata companies through some novel strategies. He achieved overall growth by adhering to the group's ethical principles and without resorting to any form of practice that would erode its reputation.

As he said in an interview in 2005, ‘What I feel most proud of is that we [the Tata Group] have been able to grow without compromising any of the values or ethical standards that we consider important” “If we had compromised them, we could have done much better, grown much faster, and perhaps been regarded as much more successful in the pure business sense. But we would have lost the one differentiation that this group has against others in the country. We would have been just another venal business house… And companies that are not good corporate citizens—those that don’t hold to standards and allow the environment and the community to suffer are the real criminals in today’s world.’

Ratan’s phenomenal success in growing Tata companies at a sharp trajectory, without compromising on principles, has made him a harbinger of a sustainable model for growth that can take the nation on faster economic growth. As a person with the highest levels of empathy, as evidenced by the very liberal benefits he extended to all those who were affected during the 26/11 attacks in Mumbai, irrespective of the fact they were employees of the Tatas, makes him a compassionate patriot. Loved by all his employees and polite, he was a gentle giant.

The world will miss him, and the nation, too, will, though the path he has shown will inspire generation after generation.

(Ratan Tata's official biographer, the author is a former IAS officer and was additional secretary to former President Pranab Mukherjee)