Remembering Stalin in Gori

Mail This Article

It is a one-hour drive through a drab countryside from Georgia’s capital Tbilisi to Gori, the village where Joseph Stalin (1878-1953) was born and lived till the age of 15. Stalin is famous and needs no introduction. Still here are a few facts to refresh memory. He was the unquestioned leader of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Communist Party for 29 years: 1924-1953. He manipulated with brutal power the destiny of post-Lenin Soviet Russia, turning it into his personal fiefdom. It was the Soviet army under his leadership that captured Berlin in 1945 and dealt the final blow to Hitler. Whether the credit goes to Stalin or to the 8.7 million Russian soldiers who died in the war is another question. As the all-powerful leader who directed the Soviet army, Stalin stands tall. In the post-war era, the same man imposed Soviet tyranny on East Europe, similar in many ways to what Hitler had done.

Nineteen million Russian civilians also died in the war - women, men and children. Perhaps these deaths can be explained by saying that an external enemy had killed them without mercy. But the horrendous internal war that Stalin unleashed on his people was equally merciless: mass murders, executions, torture-killings, fatal deportations, famines, and labour camp deaths turned Soviet Russia into a nightmare land of fear and horror. It is estimated that Stalin exterminated about 6 million Russians only to keep his power unchallenged. The killings came to be known as the Great Terror/the Great Purge. Another 3 million died under the wreckless social engineering adventures Stalin undertook, similar to those that Mao implemented with disastrous results in China.

That, in brief, was the man whose village and childhood home I was visiting. Georgia is neither Europe nor Asia. It is a sort of transcontinental entity wedged between the two. It isn’t Russian, though it was under Russian hegemony for long. The Caucasus Mountains constitute a substantial part of its geography. It is bounded by Russia to the north, Armenia to the south, Azerbaijan to the southeast, Turkey to the southwest and the Black Sea to the west. Georgians are said to be a mixture of tribes who migrated from Anatolia (Turkey) millenniums ago. Georgian is an independent language, thriving again after being long suppressed by Soviet authorities. And the food..! It is wholly unique, being a mixture of South Caucasus, Middle Eastern and Eastern European cuisines, rich and diverse and is so tasty that even the memory makes the mouth water.

Geographically and politically, Georgia always existed as a remote and insignificant corner of both the Czarist Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. It was from this obscure backyard of Russia that Joseph Stalin emerged to become the supreme leader of Soviet Russia and one of the most powerful and feared men on earth. He started learning Russian, the language in which he ruled over Soviet Russia, only at the age of nine. All his life he spoke Russian with a Georgian accent.

It was drizzling when we set out from Tbilisi for Gori. The dark sky made the dreary landscape bleaker. Our friendly taxi driver talked about politics in his broken English. He detested the very memory of the USSR. He detested even the Russian language. He said that life was hard in independent Georgia, but the freedom to be Georgians made up for everything. (Georgia became independent in 1991, with the fall of the Soviet Union.) In the occasional village that we pass, the buildings are ramshackle and the roads are bad. Agriculture is lifeless. Georgia obviously has not recovered from the effects of the decades of Soviet ‘socialist’ deprivation. It is a colourless, cheerless world. It is also very clear Stalin had not been kind even to his homeland.

Gori is a small town, shabby, faded and nothing to capture our attention except a statue of Stalin in the town square. Stalin’s and Lenin’s statues had been uprooted all over the Soviet Union after the liberation. I read somewhere that Gori retained the statue because it realized Stalin’s tourism potential. The Stalin Museum too, established during the Soviet era, remains open to visitors. Even though Stalin-centric, it is a treasure-house of historical tidbits even for those who may not be interested in history. The museum, of course, is silent about Stalin who was the Terror - except for the replica of a KGB interrogation cell, tucked away in the basement. Even the replica is terrifying.

My prize catch was on the lawn of the museum - the train carriage which Stalin used for all his long-distance travels. He had a fear of flying. (The only time he allowed himself to be flown was to attend the Tehran conference with US President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill during the war in 1943. Still, he used the train as far as it would go, from Moscow to Baku in Azerbaijan. From there he flew in a leased American Douglas-Dakota aircraft to Tehran, his first and last flight.) I was surprised by the spartan, minimal, no-luxury furnishing inside the carriage. It was truly Communist.

The home where Stalin was born is now preserved - rather, ludicrously enshrined like a holy relic - inside a pretentious Greco-Roman-style marble chapel. The whole spectacle is absurd. The small two-room hutment of young Stalin’s home looks grotesque in that grand setting. Stalin’s father, a shoemaker, had occupied one of the two rooms of the hutment with his family and the landlord the other. He was an alcoholic and a violent man. The family lived in extreme poverty. Stalin’s mother left home with her son and eked out a living working as household help. Stalin did suffer a bad childhood. The temptation to connect the dictator to that childhood is strong but I wonder if it’s so simple. There certainly are any number of people who suffered a bad childhood and yet grew up to become wonderful human beings.

It was to take young Stalin out of that dead-end that his mother sent him to the seminary of the Russian Orthodox Church in Tbilisi when he was 15. He trained for five years to become a priest. He is said to have been a topper in the religious studies of the seminary. But he left the seminary in the final year without writing the qualifying examination. Because the revolution had beckoned him.

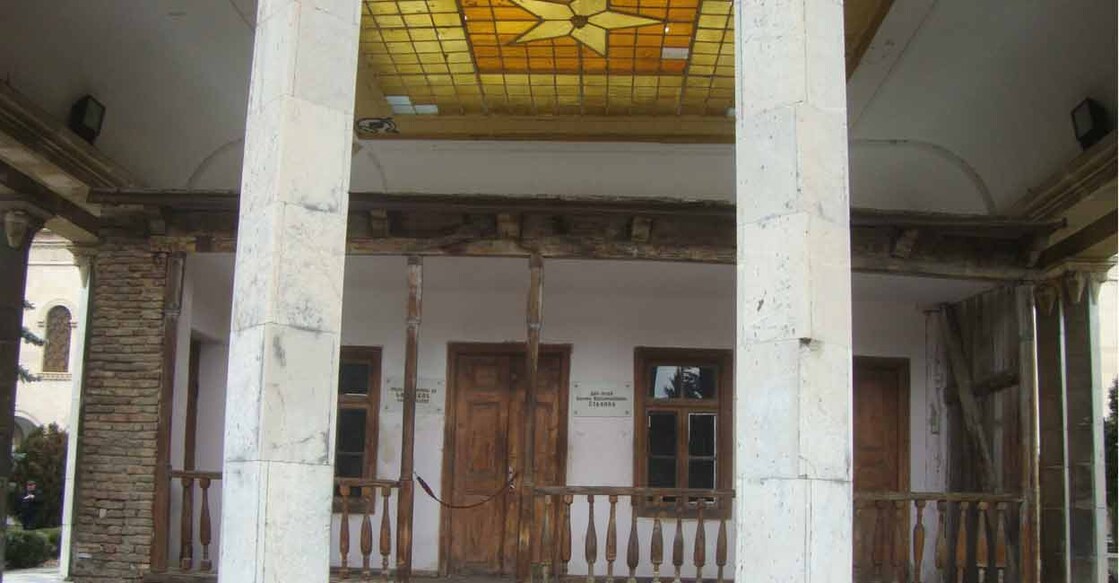

Back in Tbilisi, I went, on an evening, to the seminary where Stalin had spent five years of his adolescence and youth. I walked on its empty, silent, dimly lit veranda trying to recapture the young man who had walked there 125 years ago with a Bible in hand and prayers on his lips. It was an eerie experience. I heard history mocking me, saying: You’re a fool. History gives no guarantees. Take it or leave it.

PREVIOUS: IN MAO'S ANCESTRAL HOME

Paul Zacharia is a well-known Indian writer and columnist.