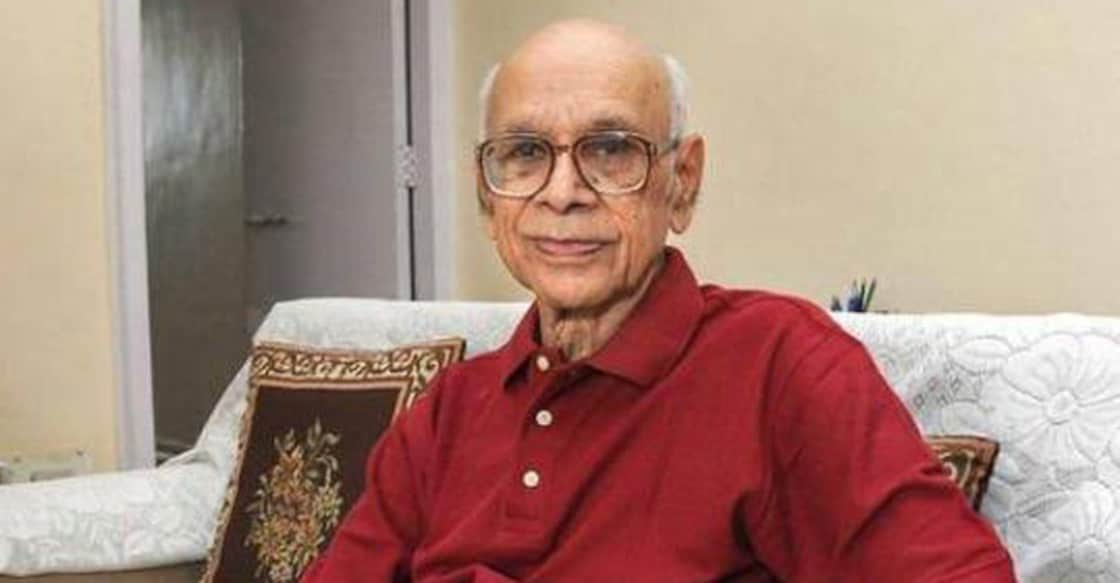

Column | Bapu Nadkarni, who bowled 131 balls at a stretch in Test without conceding a run, was a true fighter

Mail This Article

The ongoing debate over reducing the duration of Test matches from five days to four brought to one’s mind the famous observation of Fred Trueman in 1967 when India toured England. During the rest day of the first Test at Headingly, Leeds, when India were fighting to reach the three figure mark in reply to England’s first innings total of 550/4 declared, Trueman, writing in his weekly column, caustically suggested that duration of matches involving India should be reduced to four days and spectators charged less as the visitors were a “ragtag bobtail outfit masquerading as a Test match side”! History tells us that India came back strongly, led by their skipper Mansur Al Khan Pataudi, and emerged from this match with their pride intact.

Trueman’s words continue to ring in the minds of all those who felt the severe agony over the poor performances of the national side during the 1950s and 1960s. This could be one of the reasons why many of the followers of the game instinctively felt a severe distaste towards the proposal of International Cricket Council (ICC) to bring down the length of Tests to four days. One hopes that the spontaneous opposition that has arisen from persons involved in all segments of the game - players, past and present, administrators and lay followers, would convince the ICC to drop this ill perceived idea. The broad consensus is that purity of the longer version of the game at the international level should be preserved at all costs.

It is a remarkable coincidence that the demise of a player credited with bowling the most niggardly spell in Test cricket took place last week when the argument over reducing the duration of such matches was raging. Rameshchandra Gangaram Nadkarni, better known by the nickname Bapu, who passed away on January 17, earned his place in the record books by bowling 131 balls at a stretch in a Test match without conceding a run. This took place during the first Test of the series against the visiting England side, led by M J K Smith, at Chennai in January, 1964. His final figures of 32 overs with 27 maidens, conceding only five runs, in the first innings of that match would remain a record that would be extremely difficult to better in this age and time when the focus is on fast scoring and quick results.

Creditable show

But there was more to Nadkarni than his parsimonious bowling spells. He was a reasonably good batsman and has to his credit a century and seven fifties in the 41 Tests that he played. He also picked up 88 wickets in Tests, bagging more than five wickets in an innings on four occasions, while also scalping 11 wickets in a match once. Thus, he could be called an all-rounder who equipped himself moderately well in the tough world of Test cricket. He made his debut at Delhi in the third Test of the series against New Zealand in December, 1955, and played his last match also against the Kiwis, this time at Auckland in March, 1968.

Nadkarni played his first Test more as a replacement for Vinoo Mankad, the legendary all-rounder, than in his own right. Hence he was dropped when Mankad returned to the playing eleven for the next Test. During the years that followed, he was forced to watch from the sidelines till Mankad fell out of favour with the selectors towards the end of the series against the West Indies in 1958-59 that India lost 0-4. Nadkarni toured England as a member of the national squad in 1959 and gradually stabilised his place in the side.

Interrupted career

However, Nadkarni could not have an uninterrupted career at the international level on account of the arrival of a more gifted, if mercurial left-handed all-rounder named Salim Durani, with who he had to compete for a place in the national side. Durani was everything that Nadkarni was not. Durani was a handsome Pathan who believed in hitting sixes whenever the crowd demanded, irrespective of the match situation, while Nadkarni was a gritty batsman who accumulated runs slowly in singles and twos. Nadkarni could bowl hours on end without conceding too many runs with the occasional wicket being seen as a bonus while Durani was a genius with the ball who could be a match-winner on his day. Thus, it was only natural that Durani, the entertainer par excellence, was the favourite of the crowds and Nadkarni invariably had to wait for the former to commit some cricketing harakiri to get a chance to don national colours.

Nadkarni’s best moment as a bowler came in the first Test of the series against Australia at Chennai in October, 1964. He returned figures of 5/31 in the first innings as Australia crumbled to a total of 211. He followed this up with six wickets in the second innings, this time conceding 91 runs as the visitors overcame a deficit of 65 runs in the first knock to set India a target of 333 in the last innings. Though the hosts lost this Test by 139 runs, they came back strongly to win the next match by a narrow margin of two wickets to square the series. Nadkarni and Durani played in all Tests of this series as well as in the one against New Zealand that followed. But he found himself left out in the cold when the West Indies arrived in India towards the close of 1966 and was overlooked for the tour of England that followed in the summer of 1967. He was selected for the twin tours of Australia and New Zealand in 1967-68, when he played his last Test.

Accurate operator

Nadkarni’s forte as bowler was his unerring accuracy, which he developed by spending long hours in the nets, where he would bowl himself to exhaustion. He used to place a coin on the pitch and aim to land the ball on it each time he turned his arm over. It was this accuracy that helped him to keep the batsmen tied up in knots for hours on end. He rarely bowled a loose delivery, nor did he ever seek to buy wickets by “giving the air”. He epitomised frugality, which extended to wearing the loin cloth, the classical Indian undergarment, a habit that earned him the popular epithet of Bapu.

Though he was born in Nashik and played his initial years of first class cricket for Maharashtra, Nadkarni was, for all practical purposes, a ward of the old “Bombay school” of cricket, which placed a premium on playing tough and not giving up. Nadkarni was a staunch follower of the edicts of Bombay school and modelled his cricketing style accordingly. Thus occupation of crease for long hours to grind down bowling attacks, along with tying down the opposing batsmen by giving nothing away through loose deliveries, became his motto on cricketing field. There would not be any other cricketer who symbolised the essential principles of Bombay school of cricket to the extent Nadkarni had done.

The flow of tributes from the great statesmen of Mumbai cricket from Sunil Gavaskar to Sachin Tendulkar stands as evidence to the influence he wielded in forging the old and new generations of cricketers of this city. Nadkarni stood steadfast with the establishment after his retirement for which he was rewarded by the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) by being appointed as the official accompanying the national side on numerous occasions. He also used to don the hat of an expert commentator for All India Radio during Test matches played within the country.

With the demise of Nadkarni, Indian cricket bids farewell to one of its doyens who served it with stoicism and sincerity during its dark days. Cricketers of that generation played the game out of passion and pride and received nothing more than adulation and admiration from the public. They risked physical injury and financial security in choosing to continue playing the game despite the various constraints that affected their performance. Indian cricket owes it to players like Nadkarni who kept its flag flying when its fortunes were at its lowest ebb.

The best tribute that the BCCI can pay to Nadkarni would be to announce India’s disapproval of the proposal to bring down the duration of Test matches to four days. Nothing would have warmed the heart of this doughty warrior than such measures to preserve the pristine beauty of the oldest version of the game.

(The author is a former international umpire and a senior bureaucrat)