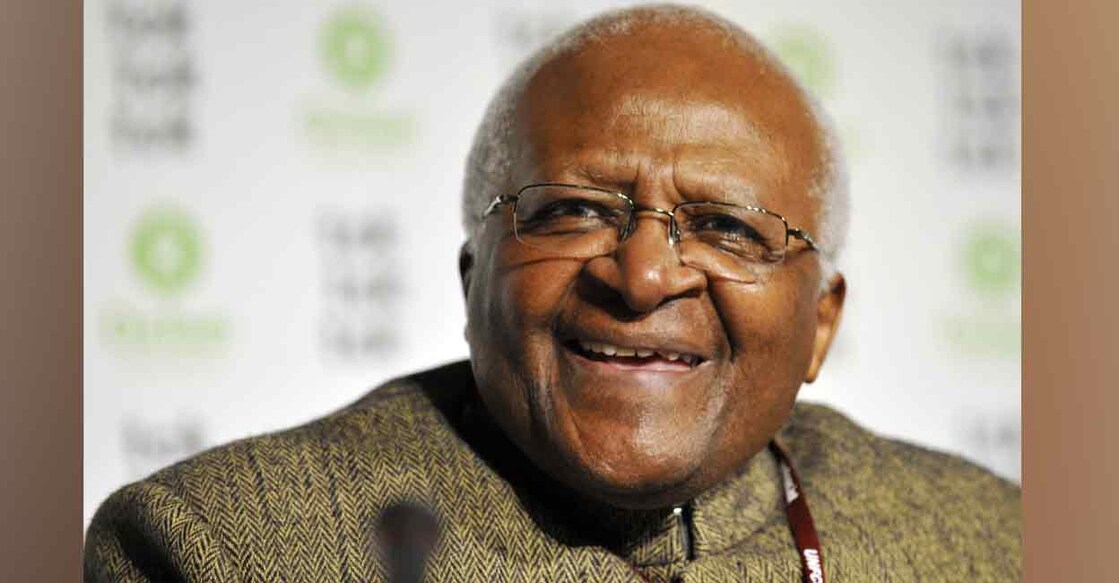

Desmond Tutu: A friend who believed in the goodness of human spirit

Mail This Article

Desmond Tutu, who passed away on December 26, not only symbolized the many strands of the anti-apartheid struggles in South Africa, but the role that education and financial support from outside the country, and of course, the gift of communication can play, even under an overpowering, violent regime.

The question that still haunts me is, how did the regime allow him to exist and speak while it was roasting and killing black people? Priest hood? The robe? The cross on the chest? The support of white clergy from the UK? Or an inimitable charm that seems to have been his shield.

Yes roasting, and this was one of those horrifying tales that Justice Albie Sachs told us when we were in South Africa - while the white soldiers roasted the meat on an open-air barbecue, if the black young man who was serving them was not complying, they would just drag his arm into the barbecue.

As we see even today, here and there, there are people and spaces where one human being sees the other as a brute - whether we use the word infidel or racial or caste slurs - a profile that justifies cruelty.

I met Desmond Tutu as a member of the Eminent Persons Group (EMP) set up by the United Nations to look into and also recommend solutions for the rehabilitation of the child soldiers who had been recruited to participate in the war in Liberia. So, when my husband Lakshmi Jain was posted as India's High Commissioner in South Africa, and Tutu was Chair of the TRC, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, I reached out to him and asked to be permitted to witness its proceedings, even though it was beamed on the television every day. A riveting drama of perpetrators, racial violence, torture and their victims confronting each other.

After every such hearing between the two parties, some solace seemed to appear and the jury tried to heal the wounds by asking the perpetrators to seek forgiveness. The anger and grief could not be wiped away, but somewhere it seemed to have provided some solace to the victims, some ventilation to the bottled-up fury - not enough as South Africa soon realised.

The high point of the proceedings was when it was Winnie Mandela's turn to apologise for her crime of killing a black young man in her entourage. There was unbearable tension in the chamber as she resisted the request - and it surprised me, as I watched, that someone from the black side did not get up, break rules and start killing the other side, the perpetrators. Desmond would not give up. He nudged, pleaded, walked down to Winnie's seat, held her close, reminded her of the remarkably brave role she had played in mobilising world opinion against the Boer regime when Mandela was in prison. She gave in and said "Sorry".

So that was Desmond’s gift, the power of his spirit, the saying of which may sound corny, but it was a breeze that pervaded the chamber. His goodness, his truthfulness, his belief in the goodness of the human spirit.

He took us personally to the Regina Munde Church in Soweto where he had protected protestors as well as galvanised the resistance. We heard about the tense moments when Mandela, out of prison, in a clean bedroom at Desmond’s home waited for Winnie, who did not come, and so many more details about the resistance, its tensions, and his friendship with Mandela.

We, Lakshmi and I, were fortunate to befriend him, a friendship that was so deep that he wished to visit us in India and experience our lifestyle and trace the vibes that shaped Lakshmi. As an aside, I have to mention here that Lakshmi's peacefulness, a big mind full of the knowledge of humankind, society, economy, and yet so modest - humble, a term he could not stop using in relation to Lakshmi - intrigued him. How did that happen? What were the circumstances, ideas, influences that formed a person like Lakshmi? So Desmond did come and stay with us in our home in Bangalore to experience that lifestyle. He insisted on wearing white khadi kurta- pajamas like Lakshmi and so it went.

Once Mandela retired, he was ignored and criticized for surrendering the opportunity to bring the apartheid rulers for trial and punishment. But he never lost his dedication to South Africa and its goodness.

He was blessed with a large family who cherished him and a strong partner in his wife Leah. He continued his mission of arguing for reconciliation, for peace, for honouring the goodness of the human being.

We used to tease him and say behave

yourself in heaven - don’t flirt with the angels - his reply was a

mischievous smile.

(Devaki Jain is an economist and Hon Fellow, St

Annes College, Oxford)