Demonetisation had adverse impact: Pranab Mukherjee in book

Mail This Article

New Delhi: The basic objectives of demonetisation have not been met and the measure has had an adverse impact on the economy and GDP growth, former President Pranab Mukherjee writes in the fourth and concluding volume of his memoirs published posthumously and released without fanfare on Tuesday. He also states that Prime Minister Narendra Modi did not discuss the issue with him in advance and that he learned about it like the rest of the country via a TV broadcast.

The release last month of select excerpts from "The Presidential Years" (Rupa) had triggered a spat between Mukherjee's son Abhijit and daughter Sharmistha, with the former demanding it be halted till he had a chance to study it and the latter urging its publication since the manuscript had been completed before her father fell sick.

"I, daughter of the author of the memoir 'The Presidential Years', request my brother Abhijit Mukherjee not to create any unnecessary hurdles in publication of the last book written by our father. He completed the manuscript before he fell sick," Sharmistha had said.

The release of the excerpts had also created waves in political circles with Mukherjee writing that Manmohan Singh was preoccupied with saving his coalition during his second stint while Narendra Modi was "autocratic" in his first term as Prime Minister. He also doesn't subscribe to the theory that the Congress would not have been drubbed in the 2014 General Elections had he been made the Prime Minister in 2004 but says the Congress "lost focus" after he was elevated to President in 2012.

Demonetisation, Mukherjee writes in the fourth volume, "has been both commended and criticized, although the jury is still out on whether it has achieved its main purpose".

Although the issue had been discussed in Parliament off and on for 17 years, "yet, when the announcement came, it brought with it a good amount of shock. Let us not forget that everyone is impacted by unaccounted cash in daily life, and unaccounted cash is amassed through the non-payment of taxes. Adequate measures were not taken to obviate the attendant problems that people faced. Further, large parts of the country continue to remain unmonetized and the practice of barter system continues in tribal areas. There is no doubt that demonetisation and the consequential decisions of the government have had an adverse impact on the economy and GDP growth, resulting in an increase in unemployment in the medium term. The informal sector of the economy, which dealt with cash, was hurt severely.

"However, it is difficult to assess the exact impact of demonetisation, close to four years after it was implemented. But perhaps one thing can be stated without fear of contradiction: that the multiple objectives of the decision of demonetisation, as stated by the government, to bring back black money, paralyse the operation of the black economy and facilitate a cashless society, etc., have not been met.

Noting that Modi had not discussed the issue with him prior to his announcement on November 8, 2016, and that he learnt of it along with the rest of the country when he made it known through a televised address to the nation. Mukherjee writes: "There has been criticism that he should have taken lawmakers and the Opposition into confidence, before making the announcement. I am of the firm opinion that demonetisation could not have been done with prior consultation because the suddenness and surprise, absolutely necessary for such announcements, would have been lost after such a process.

"Therefore, I was not surprised when he did not discuss the issue with me prior to making the public announcement. It also fitted in with his style of making dramatic announcements. According to reports, he spoke of it at a cabinet meeting and got the cabinet's consent just a short while before he went on air to tell the nation that high-value currency notes had been demonetized," Mukherjee writes.

However, after delivering his address to the nation, Modi visited Mukherjee at Rashtrapati Bhavan and explained to him the rationale behind his decision. Modi outlined three main objectives of demonetisation: tackling black money, fighting corruption and containing terror funding. "He desired an explicit support from me as a former finance minister of the country. I pointed out to him that while it was a bold step, it may lead to temporary slowdown of the economy. We would have to be extra careful to alleviate the suffering of the poor in the medium to long term. Since the announcement was made in a sudden and dramatic manner, I asked the PM if he had ensured that adequate currency was there for exchange."

"Following the meeting, I issued a statement extending support to the principle of demonetisation. I maintained that it was a bold step taken by the government that would help unearth unaccounted money as well as counterfeit currency," Mukherjee writes.

The scenario, however, panned out quite differently.

Mukherjee also notes that demonetisation wasn't an exercise initiated only by Modi.

"I remember in the early 70s, I had sent a note on demonetisation to the PMO after the successful implementation of the Voluntary Disclosure of Income and Wealth Ordinance, 1975. A large amount of concealed income and wealth was declared by defaulters who stood in queues for long hours before officers of the Income Tax Department, in the last three days before the scheme was scheduled to close. It was regarded as the most successful one among several such schemes announced earlier by ministers like Mahavir Tyagi, T.T. Krishnamachari and Morarji Desai in the late 50s and 60s.

"Indira Gandhi, however, did not accept my suggestion, pointing out that a large part of the economy was not yet fully monetized and that a substantial part of it was in the informal sector. Under these circumstances, she argued, it would be imprudent to shake the faith of people in currency notes. After all, currency notes issued by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) represent the commitment of a sovereign government. Except for the one-rupee note, which was signed by the finance secretary, all other currency notes above that value were, and are, signed by the RBI Governor.

Laying bare his thoughts on his relationship with the two Prime Ministers he worked with, who belonged to two parties and who were (and are) fiercely opposed to each other, Mukherjee writes: "I believe that the moral authority to govern vests with the PM. The overall state of the nation is reflective of the functioning of the PM and his administration.

"While Dr. Singh was preoccupied with saving the coalition, which took a toll on governance, Modi seemed to have employed a rather autocratic style of governance during his first term, as seen by the bitter relationship among the government, the legislature and the judiciary. Only time will tell if there is a better understanding on such matters in the second term of this government."

He is also frank about the reasons for the dismal showing of the Congress in the 2014 general elections, admitting candidly: "Some members of the Congress have theorized that, had I become the PM in 2004, the party might have averted the 2014 Lok Sabha drubbing.

"Though I don't subscribe to this view, I do believe that the party's leadership lost political focus after my elevation as president. While Sonia Gandhi was unable to handle the affairs of the party, Dr Singh's prolonged absence from the House put an end to any personal contact with other MPs."

Mukherjee also brings the reader closer to the inner workings of the Rashtrapati Bhavan as he reveals a minor diplomatic issue that arose during the visit of US President Barack Obama in 2015 when the US Secret Service insisted that POTUS travel in a specially armoured vehicle that had been brought from the US, and not in the car designated for use by the Indian Head of State.

"They wanted me to travel in the same armoured car along with Obama. I politely but -- firmly refused to do so, and requested the MEA to inform the US authorities that when the US president travels with the Indian President in India, he would have to trust our security arrangements. It cannot be the other way around," Mukherjee writes.

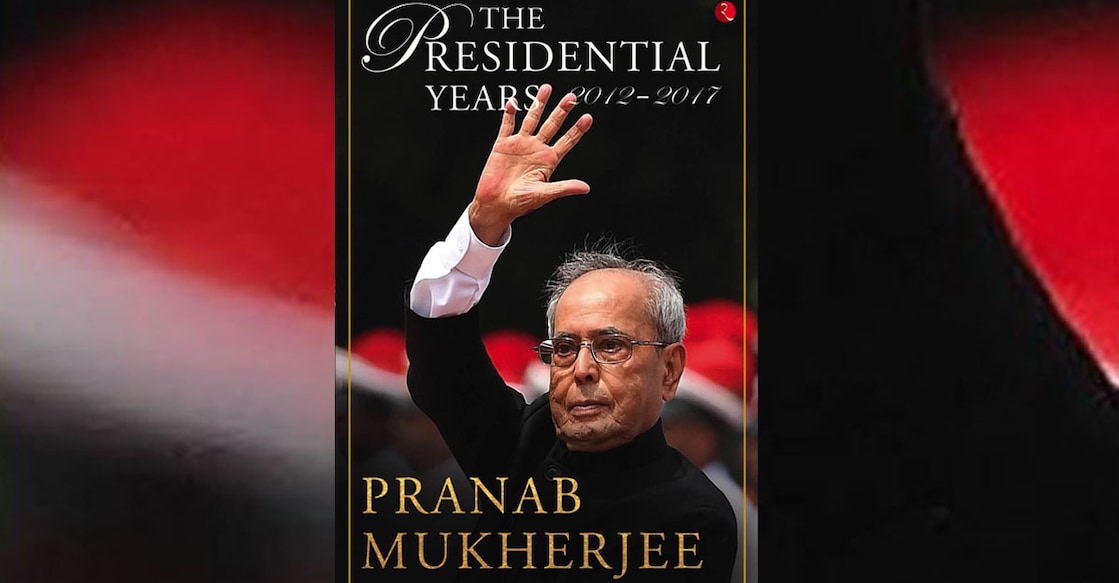

In the summer of 2012, when Mukherjee became the 13th President of India after having spent several decades in politics, there was great speculation about how he would approach his new, bipartisan role after having been associated with a political party for so many years of his life. By the time he had served his term, Mukherjee had won the respect and admiration of people from across the political spectrum, including those who were his rivals when he was a political figure.

"The Presidential Years" is the culmination of a fascinating journey that brought Mukherjee from the flicker of a lamp in a remote village in Bengal to the chandeliers of Rashtrapati Bhavan. It is a deeply personal account of the manner in which he reshaped the functioning of Rashtrapati Bhavan and responded to tumultuous events as the country's first citizen, leaving behind a legacy that will be hard to match. Pranab da, as he is affectionately called, recollects the challenges he faced in his years as President -- the difficult decisions he had to make and the tightrope walk he had to undertake to ensure that both constitutional propriety and his opinion were taken into consideration.

The first three books are titled "The Dramatic Decade" that focuses on one of the most fascinating periods in Independent India's history -- the 1970s, when Mukherjee cut his teeth and plunged headlong into national politics; "The Turbulent Years", which opens in the 1980s -- Sanjay Gandhi is dead under unexpected, tragic circumstances, not many years later, Indira Gandhi is assassinated and Rajiv Gandhi, 'the reluctant politician', abruptly becomes India's Prime Minister; and "The Coalition Years", which begins its journey in 1996 and explores the highs and lows that characterized 16 years of one of the most tumultuous periods in the nation's political history.