A few years ago, an apparently healthy pregnant woman was admitted for delivery at a hospital in Palakkad district, Kerala. Unfortunately, she developed sudden breathing difficulty and collapsed. She could not be revived despite intensive efforts by the doctors. The diagnosis was amniotic fluid embolism, a rare but serious complication of pregnancy which took the life of the mother as well as the baby—in a matter of just twenty minutes.

The grief-stricken relatives could not comprehend how a healthy young woman could suddenly die. After all, it was just a ‘routine’ pregnancy from their standpoint. As lay people, they had only seen good outcomes of pregnancy in their limited experience. Some of them concluded that it must have been the doctor’s fault.

A large mob gathered. They vandalised the hospital, assaulted the staff and dragged all the patients out, including a woman who had just delivered. They set fire to the doctor’s car, attacked the doctor’s house and didn’t spare even her dog.

The doctor and her husband survived by hiding in a store room inside her house that was also set on fire by the mob. A large police force had to be mobilised from other districts to contain the situation.

Similar incidents have occurred all over the country.

This raises several important questions

1. How can a healthy woman die from a ‘routine’ pregnancy?

2. Why did the relatives feel it was the doctor’s fault?

3. What are the ways to reduce such tragic outcomes?

4. During prenatal check-up, shouldn’t doctors be counselling each patient and family about all the potential complications of pregnancy? Are relatives reluctant to hear about risks?

5. Isn’t violence against doctors and hospitals a criminal offence with a non-bailable clause?

Pregnancy is central to existence of life - and is a phenomenon that borders on the magical. In the case of humans, it is associated with joy, hope and celebration in most cases. However, in the midst of such positive emotional response to pregnancy, the perils or dangers are often forgotten.

Even an apparently ‘routine’ pregnancy can turn life-threatening for the mother and baby, though medical science has helped reduce the risks greatly. Naturally, no one likes to hear bad things about a joyful event – and therefore, public awareness about the downside of pregnancy is lacking.

This article is written to discuss a few important complications of pregnancy, methods to bring down maternal mortality, the need for greater awareness among the general public and the importance of effective doctor-patient communication.

Isn’t pregnancy a normal physiological condition?

This is a controversial question. In medical literature, normal and physiological are terms that are used to describe routine things like walking, hearing, breathing, sweating, digestion and so on. Though biologically an expected phenomenon, many experts believe that pregnancy cannot strictly be classified as ‘normal’. The reason is that unlike other normal physiological processes, a substantial number of pregnancies adversely affect the health and threaten the life of the mother and the child. Death related to childbirth is a major public health problem worldwide.

Such bad outcomes are particularly common in societies that lack access to good quality healthcare, but are also known to occur in spite of the most advanced medical facilities.

When is pregnancy an unhappy event?

Though in the vast majority of cases it is a joyous event, situations such as unplanned pregnancy from rape, lack of choice or lack of access to contraception are generally perceived otherwise. Due to the prevailing circumstances, such pregnancies are also more likely to develop complications.

How often do women die at childbirth?

Heart-breaking as it is, death of a mother at childbirth can occur from a variety of causes. In technical terms, it is called maternal mortality ratio (MMR), one of the key indices of public health.

In parts of Africa such as Nigeria, out of every 100,000 deliveries, 814 women die. In India, out of every 100,000 deliveries, 174 women die. Although India’s MMR figures are better than previous years, this is still one out of 574 women, a staggering number for a country of 1.3 billion people . Put another way, hypothetically if all the women living in India now had two full term pregnancies in their lifetime, that would leave over two million women dead.

Among developed nations, the US has a maternal mortality of 26 per 100,000, which is surprisingly high when compared to other countries such as Sweden (4) and Germany (9). One might wonder why the US has greater maternal death rates despite having top quality hospitals and doctors.

The key factor here is not whether the best facilities are available, but whether everyone who lives in a country has access to such services. One reason for higher than expected maternal mortality in the US is that certain underprivileged sections of society do not receive state of the art medical care.

A parallel applies to India, which is also a large country with heterogenous spread of healthcare facilities. A large number of women still do not have access to basic healthcare. Even in areas that have modern healthcare facilities, abortions performed by quacks and home deliveries by untrained workers are common. The recent death of a mother at Manjeri, Kerala following attempted water-birth by a naturopathic practitioner is a case in point.

Thanks to a large network of hospitals, clinics and trained personnel, Kerala has achieved a relatively low MMR of 50, compared to Assam (300) and Uttar Pradesh (285).

Why do mothers die after giving birth?

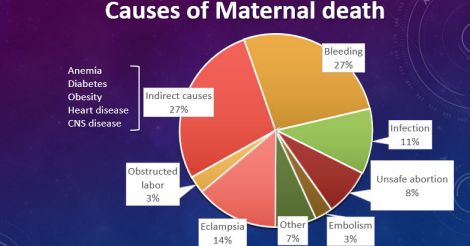

All over the world, the top cause of maternal death is severe bleeding from the uterus after delivery, also called postpartum haemorrhage.

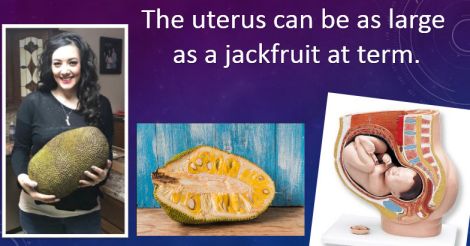

As the fetus enlarges during pregnancy, the uterus also gradually enlarges 25-fold to reach the size of a jackfruit, so that it can securely hold a 3 kg baby inside. Every minute, as much as ¾ litre of blood flows through the uterus at full term.

Immediately after delivery, the uterus has to shrink from the size of a jackfruit to a much smaller size. This step is essential to prevent blood loss after delivery.

However, like an umbrella that gets stuck in open position and refuses to shut, If the uterus fails to shrink, profuse bleeding can occur, sometimes leading to death.

Another complication that is fortunately rare but extremely serious is amniotic fluid embolism. Amniotic fluid enters the mother’s blood stream and causes a severe reaction, leading to cardiorespiratory collapse and uncontrolled bleeding. This can come on without warning; death is a common outcome. Amniotic fluid embolism cannot be prevented.

Sluggish circulation can lead to blood clots in the leg veins of people who are physically inactive. Such clots can sometimes dislodge and travel upstream to the large blood vessels in the lungs, causing a serious and potentially fatal condition. It is called pulmonary embolism. This can be prevented to some extent by avoiding unnecessary ‘bed rest’, a common mistake made by pregnant women—frequently on the basis of unqualified advice. In fact, there are very few conditions in pregnancy that actually require bed rest.

It is estimated that for every maternal death, there are at least 20 others who escape death, but suffer from severe illnesses related to pregnancy.

A discussion of all the complications of pregnancy is not the purpose of this article, but it is clear that knowingly or unknowingly, every mother is risking her own life—each time she bears a child.

A detailed paper on maternal mortality is included in the further reading section.

The importance of community awareness, and the near-miss ratio

All over the world, lack of awareness leads to bad outcomes of pregnancy due to failure to seek or follow systematic obstetric care. It should be noted that most complications can be treated when diagnosed promptly and protocols are followed. However, those who are ignorant tend to take pregnancy lightly, often preferring not to attend regular check-ups. Such people will not be able to recognise complications or get treated early enough.

In obstetrics, the term ‘near-miss’ is used for such cases where a serious complication occurs, but the patient escapes death due to prompt obstetric care. There is a near-miss:mortality ratio which indicates how efficient the system is in dealing with complications.

The higher the ratio, the better the standards are. For instance, in parts of India, the ratio is 3:1, which means that for every three major complications, one death occurs. In developed countries, this ratio is 100:1 or even 200:1, which means that the chance of dying after a complication is much less.

One of the factors that drives this ratio higher in developed nations is greater community awareness about pregnancy as a medical condition, and the willingness to work together with the obstetrics team. As the saying goes, a stitch in time saves nine. Early recognition is the key towards prompt treatment and good outcomes.

What is the best way to improve awareness?

Attending antenatal classes and talking with experienced healthcare personnel is the ideal way to know more about pregnancy and its complications. Searching the internet for information can trigger unwarranted anxiety as explained in my earlier article titled “Google vs. Doctor”.

Why is doctor-patient communication important?

At least a few would argue that pregnancy is a happy occasion and therefore doctors need not discuss complications with every pregnant woman until and unless they happen. However, it is important for the general public to become aware that pregnancy need not always be smooth ride, and that complications are an integral part of the picture.

Widespread ignorance leads to confusion and needless finger-pointing occur when complications arise. Part of the reason is that a section of the general public expects 100% of pregnancies to have a safe and healthy outcome. Consequently, in this part of the world, it is becoming increasingly common to blame the hospital and the doctor for any adverse outcome of pregnancy.

Doctors have a significant role to play in educating the public, and must counsel the expectant mother, her husband and family about the big picture. Time spent on dispelling regional myths about pregnancy will help reduce the mother’s suffering.

Counseling must include a discussion on complications, and tips to recognise and prevent them. With good communication skills and the help of professional visual aids such as videos, it is possible to convey potentially morbid information in a manner that does not cause alarm.

Communication tips from being on a flight

While on a plane, the in-flight safety instructions narrated by the crew are a typical example of saying what needs to be said without causing panic. When they say ‘in the case of a water landing’, what they really mean is the flight crashing onto the sea, and when they discuss oxygen masks, they simply use the phrase “in case of a drop in cabin pressure” instead of more horrifying terms.

Just as individual airlines provide essentially the same information for all of their passengers, regional professional societies can put together a common template of information or teaching video on pregnancy. If required, these can be customised for each practice setting. In an aircraft, it is the crew and not the pilot who counsels the passengers. Likewise, using these templates and videos, trained nurses and other staff can also help with patient education.

This in turn frees up time for the doctor, which can be used to examine patients, take clinical decisions and answer any further queries.

All of these innovative measures will ensure that the general public receives accurate and consistent information about pregnancy.

Cultural factors that affect communication:

When doctors communicate with patients, explaining the concept of risk and probability can be difficult due to various educational, language and cultural factors. For instance, to someone who cannot understand a fraction, phrases like “the risk of severe bleeding is 6 in 1000” will make no sense. To the non-medically trained, the work ‘risk’ literally means ‘dangerous’, whereas in medical parlance it only means ‘statistical probability of an adverse event’.

Although they claim to want to know everything, patients in India generally prefer not to hear anything negative about their medical condition, treatment or procedures. Unlike the west, they frequently react with distrust and fear when words such as ‘risk’, ‘side effects’ or ‘complication’ are mentioned. Though ethically bound to discuss the pros as well as the cons, doctors in India are often reluctant to discuss such matters, and this contributes to ignorance.

How to effectively explain the downside to a patient?

Rather than quote technical terms and numbers from a text book, doctors may use everyday examples that are familiar to the lay person while explaining.

An easy teaching example that can be used in India to explain the concept of risk is to compare pregnancy with crossing a busy road. Most often, we reach the other side safely. However, we know that sometimes, accidents do happen. That is why we must first make sure we are fit enough to cross the road, and also look around carefully while crossing the road.

Going through pregnancy without professional help will be like crossing the road with our eyes closed. Though in many cases we would survive, the chance (risk) of an accident is higher.

Ignorance can be costly

The price of ignorance can be heavy. The worst outcome is loss of life of the mother or the baby. A distraught family that is ignorant about the complications of pregnancy might wrongly blame the doctor or hospital for the outcome, and even resort to violence. One of the root causes of hospital attacks in India is such ignorance.

As outlined above, a large number of causes exist for maternal mortality. Although occasional errors can happen in healthcare just like in any other system, the likelihood of the attending doctor making a mistake that directly leads to a mother’s death is exceedingly rare. Doctors as well as the general public need to work together to dispel the prevailing myth that any complication of pregnancy is the fault of the doctor or the hospital.

The public must understand that there are civil ways of raising concerns and addressing grievances. Acts of violence against hospitals, doctors and healthcare staff are cognizable and non-bailable by the hospital protection act passed in 2012 by the Government of Kerala.

Such acts of violence and increasingly litigious approach by society will have far-reaching consequences on the healthcare system. In Kerala, there is already a palpable lack of interest among young doctors to take up obstetrics as their career. Those doctors who take up Ob-Gyn training, prefer to do laparoscopy and infertility work rather than attend deliveries. Smaller hospitals in Kerala are increasingly reluctant to accept cases of high risk pregnancy. This will affect the quality of community obstetric care in the long-term.

It is noteworthy that in the US, the adverse medicolegal climate has made it hard to find a qualified obstetrician in many counties—this is one of the cited reasons for the recent rise in maternal mortality rate.

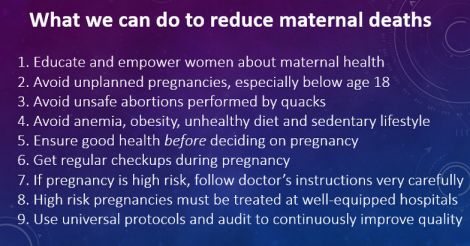

How can we reduce maternal mortality?

The vast majority of pregnancies have a good outcome. A major task is to identify those pregnancies where complications are more likely to occur. With modern technology and updated treatment protocols, doctors will be able to identify those high-risk pregnancies, and take steps to minimise risk.

As can be seen from the Kerala and US example, to make a meaningful impact on maternal mortality, universal access to skilled healthcare personnel is more important for the region as a whole, rather than setting up some state-of-the art hospitals that can only be accessed by a few. Overcrowding of hospitals, lack of equipment and human resource shortage can dilute the quality of care delivered. Not all complications can be predicted. Maintaining protocols and seamless referral services are therefore important.

Audit and analysis of maternal deaths and complications will help reduce future mortality. A glowing example is the confidential reporting of maternal deaths (CRMD), Kerala, which is based on the UK system of CEMD (confidential enquiry into maternal deaths) to better understand and rectify the factors leading to bad outcomes.

Through such systematic reporting and scientific analysis followed by effective intervention, maternal mortality rates can be further reduced. To quote a related example, the safety we enjoy today while flying is the result of the meticulous reporting and analysis of many aviation accidents that occurred in the past.

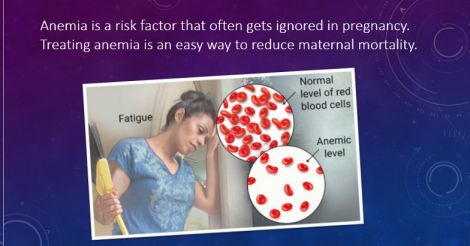

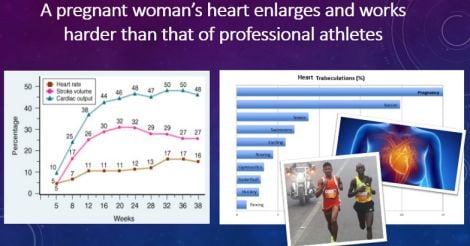

To reduce maternal mortality, factors preceding pregnancy also need to be addressed. For instance, the cardiovascular changes that happen in a woman’s body during pregnancy can rival that of an athlete preparing for an Olympic event. In other words, pregnancy is a task that must be attempted only by the healthy. Unfortunately, not all women who become pregnant are in good health prior. Such people are at greater risk of bad outcomes. For instance, women at extremes of age, those who are anaemic or obese, and those with frequent or multiple pregnancies are particularly vulnerable.

In addition to physical health, mental health during and after pregnancy requires special attention; CRMD in Kerala found suicides as one of the causes of maternal mortality. Screening for depression and domestic stress can help prevent bad outcomes.

Women must empower themselves with learning, and acquire good-quality information on health even before they choose to become pregnant. The healthier a woman and her environment are before pregnancy, the better the outcome is. Therefore, improving physical and mental fitness with regular exercise, healthful diet and social support are important in the months leading up to pregnancy, as well as during gestation.

Further reading

1. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis

2. Near-miss : Mortality ratio and its importance in obstetrics

3. Functioning of the heart during pregnancy

6. Searching the internet for health information can trigger unwarranted anxiety.

All the images used in the column are sourced by Dr Rajeev Jayadevan

(The author is a senior consultant gastroenterologist and deputy medical director, Sunrise group of hospitals)

Photo: Getty Images

Photo: Getty Images