“Indians love really loud music,” proclaims a TV ad trying to promote a mobile phone, the words coming from a person possibly of Scandinavian origin holding the phone out for us to see, with the beat of the catchy item-song “Beedi” playing in the background.

At a deeper level, we can see why he said that: compared to western nations, there is a lot of noise in India, and it isn’t just from music. At home, noise comes from appliances such as TV, radio, mixer-grinder and earphones plugged into mobile phones, not to mention loud conversation. Outside of our home, noise emanates from construction and traffic congestion with incessant honking. This is made worse by public address systems with powerful loudspeakers that disseminate noise over miles, a sample of which we recently heard during the assembly elections. While some of these might seem trivial, the cumulative effect is huge and takes a toll on our body.

Exposure to noise causes slow but incurable deafness, high blood pressure, heart disease, anxiety, restlessness, disturbed sleep and poor school performance in children.

In contrast, those who have lived abroad will recall how peaceful and quiet the surroundings were, with the friendly chirping of birds and an occasional passing vehicle being about the only source of noise in the suburbs and rural areas. Loudspeakers and honking are virtually non-existent.

Is noise a pollutant?

Pollution is a term that we superficially attribute to dust, smoke and contamination of water supply.

However, technically, pollution is defined as the introduction of matter or energy into the environment that causes harm. Noise is such a form of energy that is often ignored by laymen as a source of pollution, partly because it is invisible, and doesn’t stink.

The polluting substance, whether it is smoke or a chemical, enters our body without our permission, through the air we breathe and the water we drink.

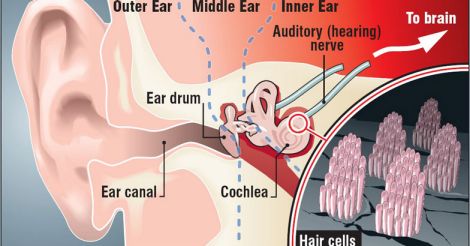

Similarly, noise freely enters our ear canals, whether we like it or not, and causes damage. It is noteworthy that unlike our eyes that have lids that can be closed on command, our ears don’t come with built-in flaps. This means that we are left with no choice but to suffer the loud noise that someone else might be making.

The slow death of hair cells: how noise damages our hearing

As sound waves enter our ear canal, the vibrations created on the ear drum travel to the internal ear through tiny bones called ossicles. These bones are connected with the cochlea, a highly sensitive and complex hearing organ. Shaped like a snail and filled with fluid in which thread-like extensions of delicate nerve (‘hair’) cells dance gently, the cochlea converts mechanical energy to electrical energy, much like a bicycle dynamo. (Note that ‘hair cells’ have nothing to do with hair)

The electrical signals then travel to the brain through the auditory nerve, where they are finally decoded into recognisable data.

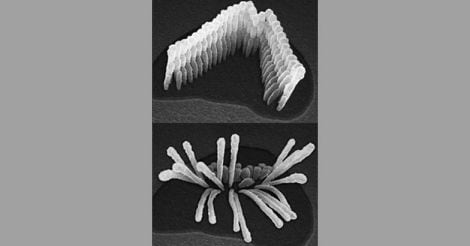

During silence, the surface of the hair cells appears like a healthy paddy field, with all the leaves waving uniformly and gently in the breeze. After exposure to loud noise, they get randomly flattened, just like when a cyclone would have hit the paddy field.

Nerve cells inside our ear get easily damaged by loud noise.

Nerve cells inside our ear get easily damaged by loud noise.While recovery is the general rule, repeated exposure to loud noise over extended periods of time kills some of these cells. Unlike amphibian hair cells, human hair cells cannot grow back. Their number is finite. As a few hair cells die, the ability to hear certain selected frequencies of sound gets compromised. This is called high frequency hearing loss, and need not be apparent to the sufferer in early stages. As the number gets further depleted, pronounced hearing loss occurs, which unfortunately cannot be corrected by a hearing aid. Remember that a hearing aid can only amplify the sound waves entering the ear, and will not help if the internal hearing organ is damaged. (If a bicycle dynamo is damaged, pedalling faster does not make your headlamp glow)

How noise affects other parts of the body:

High blood pressure and heart disease are well-known to occur among those with prolonged noise exposure. Sound waves can interfere with the working of baroceptors - delicate pressure sensors located in our blood vessels. High levels of the fight-or-flight hormone adrenalin are also found.

Noise exposure at night interferes with certain stages of sleep (REM sleep); as a result people, do not feel rested the day after. Anxiety, restlessness and anger spells are consequences of noise exposure.

It is worth noting that many airports in Europe do not allow noisy types of aircraft to take off or land between the hours of 11 PM and 7 AM. Several airports in India, including CIAL, have recently transformed into ‘silent airports’ by banning public announcements.

Noise and children

Children have the habit of using earphones to quietly listen to their own brand of music without inviting the disapproval of adults. They may turn up the volume for the thrill of it and in the process, damage the nerve cells located in their cochlea. As a result, they get selective hearing loss, and may not comprehend everything the teacher says in class. Besides, they experience difficulty concentrating when exposed to noise from any source. Noise exposure is well-known to affect scholastic performance.

What can we do to reduce noise pollution? Is there a cultural influence?

There are laws in place against noise pollution, but experts say it will be difficult to bring on change without building awareness first, owing to some cultural barriers.

Unfortunately in India, noise has long been associated with positive emotions such as festivals and celebrations. This cultural factor, when coupled with low general awareness levels on this topic, will make it hard to convince someone that noise must be curbed.

We experienced a recent surge in noise pollution during the Kerala assembly elections. Vehicles carrying over-sized loudspeakers blaring recorded speeches and parodies of popular film songs drove through even the smallest roads in the densely populated state, thrusting hundreds of decibels of noise into the unsuspecting ears of all inhabitants.

Contrast this with the recently concluded presidential elections in Sri Lanka, a tiny nation with cultural and socioeconomic similarity to India. The Sri Lankan elections were largely a silent affair, with only a few loud speakers being used - only in permitted areas such as open fields/stadiums that were authorised for this purpose. It doesn’t stop there. While driving, the Sri Lankans don’t honk their horn even on a crowded road, and always behave courteously to fellow drivers. Incidentally, Sri Lankans do not litter their streets.

While searching for workable solutions, it is worth pondering how Sri Lanka got ahead of us in civic sense. It can’t be because they are an economically developed nation like Germany or Sweden, and it can’t be from better law enforcement alone. If Sri Lanka could do it, India could too.

When discussing the influence of local culture on the effectiveness of health campaigns, a parallel can be drawn between smoking and noise pollution. Note that smoking was culturally accepted for several decades, even though doctors had warned about it. After years of awareness-building and involvement of the mass media, judiciary and law-enforcement, smoking has finally been curbed. The anti noise pollution drive, in a similar vein, will likely evolve through several stages before becoming effective in a large country like ours.

The Indian Medical Association has highlighted this problem for the past decade, and even secured orders from the High Court of Kerala and from the National Green Tribunal to help maintain silence zones. Their initiative called NISS (National initiative for safe sound) has brought about considerable awareness about this topic. Doctors have interacted with all cross-sections of society and held discussions involving the general public, to help understand the situation better and devise meaningful steps in the Indian context. The following recommendations were put forward.

WAYS TO REDUCE NOISE POLLUTION IN INDIA

1. Noise is a pollutant. People need to first become aware of this fact before meaningful change can happen. Mass media can help with this.

2. Change is best initiated at home. Each one of us can make small changes – such as reducing the volume of radio or TV, using softer tones during conversation, and reducing overall noise output during celebrations such as weddings, birthdays and festivals. If all residents’ associations discussed this topic at their meetings, it will facilitate compliance.

3. Children must be cautioned to reduce volume of earphones. If the reason is explained clearly, they are more likely to comply.

4. Unnecessary horn use has to stop; this calls for a major change in driving culture. Horn use must be restricted only to warn someone of danger, and not as a device to intimidate/irritate other road users. On a good note, it is laudable that in the city of Kochi, honking has declined among private car owners, thanks largely to the Horn Not OK campaign.

5. Office-bearers of all religious institutions have stated that loudspeaker use and sound levels must be reduced, and that they will spread this message among their peers and followers. They have said that places of worship are fundamentally meant for the goodness of all living beings, and should not be polluting our peaceful environment. When fireworks are used, noise level can be selectively minimised without compromising visual splendour.

6. Noise output from public address systems should be regulated diligently. Sound operators need continued awareness programs and practice compliance with the law.

7. Industrial noise output needs to be monitored and ear-protective equipment used when indicated.

8. All public noise must be minimised during the hours of sleep.

9. Even if the majority of the general public were to willingly reduce their noise output, there are bound to be a few outliers whose rogue conduct will undo all the collective good. Support from law enforcement personnel is therefore essential in reducing noise pollution.

What does it cost to curb noise pollution?

From India’s perspective, unlike all other social and infrastructure improvements that are expensive, reducing noise levels costs us almost nothing, and in fact saves money in the long-term.

(The author is a senior consultant gastroenterologist and the deputy medical director, Sunrise Group of Hospitals, Kochi.)