A study was done in Israel about the chances of a prisoner getting parole from the judge in court.

It was found that the first few prisoners who appeared in court during the day had a greater chance of getting parole, while the last appointments of the court session were almost always denied parole by the same judge.

Why did this happen? The reason was information overload leading to decision fatigue.

To decide each time whether to give parole or not requires active brain work. As the day progressed, the judge was bombarded with more and more information, and his brain was fatigued from taking decisions. Towards the end of the session, the judge was no longer able to process the information provided. As he could not decide whether the prisoner really deserved parole, he took the safe option - that was to deny.

Also read: Everyday Health | The basics about pain and painkillers: a user’s guide

What is Information Overload?

Information overload, also termed cognitive overload - occurs when the brain gets overwhelmed by massive amounts of information and fails to process it any more.

Also read: Everyday Health | It is possible to defeat colon cancer -- if we are proactive

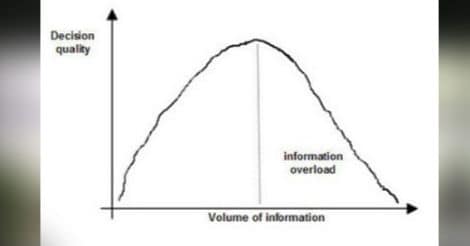

Why is too much information a problem? It is obvious that a certain amount of good-quality information is required to make rational decisions. But when the amount of information is far in excess of what the brain can handle, our decision-making capacity and memory power declines. We end up making bad decisions that support our own bias, or no decision at all – the latter laying the foundation for procrastination.

Information overload: as the amount of available information increases, quality of decisions initially improves, but later declines

Information overload: as the amount of available information increases, quality of decisions initially improves, but later declinesWe seldom realize that for every bit of information that we receive - whether it is something we requested for or not - we spend brain-processing power and energy. First, we need to analyze it, compare it with similar stored information in our memory bank, decide whether we need to act on it and then decide whether we should ignore it, memorize it or pass it on to someone else. Each of these steps saps the brain’s energy. However, a large chunk of the information that reaches our brain is of no use to us in our professional or personal life, which means that we are wasting a lot of brain energy by trying to process it.

The threat of information overload is real. Going by current trends, it is about to get a whole lot worse. How to survive the information glut without falling behind is an art, and a science. This article uncovers the fascinating details of this phenomenon, and provides workable solutions.

Handling information is like eating sensibly at a buffet. Too much can cause trouble.

Handling information is like eating sensibly at a buffet. Too much can cause trouble.

Tim Ferris in his bestselling book The 4-Hour Body talks about MED or minimum effective dose for medications: the least dose that produces the desired benefit without causing harm. Likewise, the right dose of information can produce the desired benefit, while excess information can be harmful.

What is the source of such excess information?

Historically, the quantity of information available to man took a big leap forward with the discovery of the printing press in the 15th century, when books could be mass-produced. Newspapers arrived next, helping spread information quickly on a larger scale. This was followed by radio, telephone, TV, computers, Internet and smartphones.

It is said that a single Sunday newspaper of today contains as much information as was available during the entire lifetime of an average person living in the 17th century. With over 4.7 billion indexed pages already, (that is 4 followed by nine zeros) the amount of information available on the Internet doubles every 13 months.

In addition, with the advent of social media, each individual now has the power to create and disseminate information across the globe at almost no cost.

However, even as more information became available to man at each step, our brain itself has not received an upgrade in thousands of years.

A typical day of information overload

By the time the day starts, we would have checked social media for new messages, and responded to several. We would also have read the newspaper, listened to the radio, and watched the morning news on TV. In addition, numerous news portals and apps with their push notifications serve the latest in weather, stock prices, celebrity gossip, sports, market trends, crime stories and political developments right on to our smartphone screen.

Already brimming with information, as we commute to work, there are several radio stations to listen to, in addition to billboards and posters on the way, each of which provides a fair share of ads from businesses interested in promoting their products.

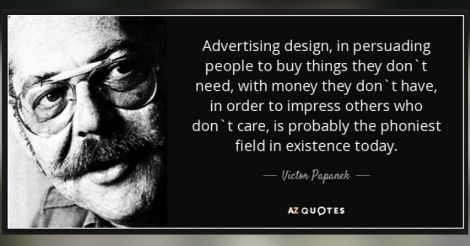

While advertising on any medium is a legitimate means for a vendor to showcase their product, from a listener’s or viewer’s standpoint, it still is unsolicited information – which means information that we did not actively seek. The Internet brings with it targeted advertising, using artificial intelligence to silently analyze our browsing preferences and cleverly sending us ads on products we might be interested in.

Ads might seem appealing, but could lead us into buying things we don’t need by first planting desire in our minds. A fatigued mind can convert this desire into an impulsive purchase decision.

Ads might seem appealing, but could lead us into buying things we don’t need by first planting desire in our minds. A fatigued mind can convert this desire into an impulsive purchase decision.

Once at work, some of us sort through over a hundred emails daily, many of which are junk. Social media use at work is commonplace, contributing generously to information excess. Once we get back home, the TV comes back on, and we read the remaining sections of the newspaper and our favorite magazines, not forgetting to check our news apps and social media - just in case we missed out on something during the day.

While at first glance, all of this might seem routine (with some individual variations), the big question is, how much of this information is useful to us? Unfortunately, a large portion of it is unsolicited information: that is information that got drilled into our heads at the behest of someone else. The bigger question is: how is all of this information going to affect our mindset and productivity?

WhatsApp and Facebook use take up a significant part of the day for many, contributing to information overload and mental fatigue. It could hurt the economy and productivity if used during work hours.

WhatsApp and Facebook use take up a significant part of the day for many, contributing to information overload and mental fatigue. It could hurt the economy and productivity if used during work hours.Unfortunately, a lot of the forwarded information on social media happens to be hoaxes or junk messages that travel endlessly around the globe because most people who receive them do not spare the time to verify the authenticity. Instead, they choose the easy way out: pass it on to their contacts, ‘just in case’ it is useful to someone. The topic of fake information in circulation was explained in my earlier article on hoaxes.

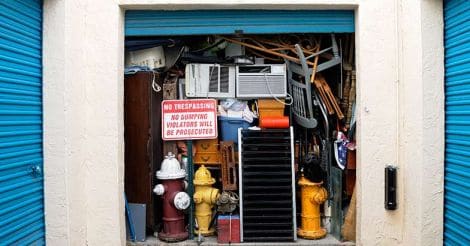

This ‘just-in-case’ principle is the reason many of us make an effort to read and memorize a lot of the information made available to us. Like the case of the compulsive hoarder, we assume that the information, although not relevant now, might be helpful at some point in the future. It is worth mentioning that the Internet allows us the luxury of searching for information at anytime, therefore the need to read and store everything in memory isn’t as much as it was thirty years ago.

Hoarding is a psychological disorder that makes people collect and store physical objects compulsively. Information overload occurs when we collect and store all the information we come across.

Hoarding is a psychological disorder that makes people collect and store physical objects compulsively. Information overload occurs when we collect and store all the information we come across.

In modern times, don’t we need to stay updated with everything?

It is true that compared to fifty years ago, life has become more complex now and we are expected to know greater amounts of information. For example, “knowledge of current affairs” is frequently tested in interviews and exams, and is also the subject of casual conversation. Shutting out information is definitely not an option. But how much of current affairs should we know? Are we able to distinguish between necessary, important, interesting, unimportant and trash?

Does it really make a difference if we know everything about a bus accident that happened halfway across the world? Week after week, do we really need to discuss on TV the same gory details of a crime that happened three months ago? Why do we need to know all the spicy rumors behind the divorce of a film actor?

Where do we draw the line between genuine desire for information and schadenfreude, the innate human tendency to relish the misfortune that happens to a fellow human being?

But aren’t we good at multitasking?

Multi-tasking refers to the hypothetical ability to focus on and perform multiple tasks at one time. Though the term is attractive and self-idolizing, studies have shown that human beings are not really good at multitasking. According to neuroscientist Daniel J. Levitin who wrote the book The Organised Mind, we are better at uni-tasking (performing a single task well) than multitasking.

In fact, we can only switch from one task to another. When we attempt multitasking, our brain cells come under stress to switch focus from one task to the other, and this takes up energy and resources which could have been used elsewhere in the brain. Multitasking is considered unsuitable for creativity and problem-solving, which require sustained thought process.

Most of us are not born multi-taskers. Though not always practical, it is better to focus on one task at a time, and to filter out all other distracting information during that process. It is estimated that only one out of 40 people are born with true multitasking ability.

How does the brain work, and what is decision fatigue?

Though we might not be aware of it, our brain is constantly executing decisions based on visual, auditory and other information we receive. When our brain gets overwhelmed at this, we suffer from decision-fatigue.

Brain cells are expensive to maintain. They require a lot of energy to work - in fact their metabolic rate is 7.5 times that of other cells. Each time a signal reaches the brain cell, ions move back and forth across the cell membrane. The cell then consumes more energy to stabilize the ion concentration across its membrane. The harder we make our brain work, the greater the energy need. This energy comes almost exclusively from blood glucose, and that is the reason why we feel mentally fatigued while hungry.

According to neuroscientists, even a seemingly simple task such as shopping at a supermarket involves numerous on-the-spot decisions: we have to browse the products, first decide which of the several products that are on display are not meant for us and then choose which one to buy - all of these are individual decisions performed by our brain. The more we browse, the more number of times our brain cells fire - and the greater the decision-fatigue.

Research has shown that shopping while hungry can make us buy more than we need and spend more money, and not just on food-related purchases. This is from impaired decision-making after information overload, a situation compounded by lack of fuel for brain cells.

Research has shown that shopping while hungry can make us buy more than we need and spend more money, and not just on food-related purchases. This is from impaired decision-making after information overload, a situation compounded by lack of fuel for brain cells.Supermarkets take advantage of customers’ decision fatigue. They know that by the time the customer has done the rounds of the aisles, his brain would be tired and unable to make sound decisions. Hence, they display tempting items like chocolate, candy and gossip magazines along the sides of the checkout counter. The fatigued customer is more likely to buy these on impulse than if these items were presented at the entrance to the supermarket, when the mind was fresh and better judgment would have prevailed.

The same principle applies to checking an email or social media post. We make a large number of decisions at each step such as:

1. Should I be reading this? Yes/No/Why?

2. When is the best time to read this? Now/Later/Why?

3. Should I move it into my office folder? Yes/No/Why?

4. Should I reply now or later? Yes/No/Why?

5. Should I forward it to my colleagues? Yes/No/Why?

6. Should I mark it as spam and delete it? Yes/No/Why?

What is interesting here is that in spite of exercising our brainpower and decision-making capacity, nothing worthwhile was achieved. It is like stepping on the accelerator while the car’s tyres are not touching the ground.

If we take so many decisions with each email or social media post that we encounter, the enormity of the stress we put our brain through during an average day at work can only be imagined. Our overall efficiency drops, and we suffer from indecisiveness, fatigue and confusion after a while, with lapses in memory and poor concentration. Studies have shown that those who are frequently interrupted by email and phone calls while at work can suffer a lowering of their IQ.

The mushrooming of Whatsapp groups and ever-expanding ‘friend-lists’ on FaceBook only compounds the problem: apart from a few genuine messages and useful updates from our social contacts, a good portion of what we read is forwarded stuff we might actually have no interest in. Besides, the same information is frequently seen circulating in dozens of groups that many people are now members of.

Decision fatigue at work can lead us to make wrong decisions, delay important decisions, splurge on junk food against our better judgment, and even drive us to make foolish, expensive and impulsive purchases. Such people also seem to be in a perpetual hurry and may suffer from depression in the long term.

Water woes

Deciding the type of water to drink in an upscale restaurant is another example of unnecessary brain use. As soon as we are seated, the waiter approaches, asking whether we want water or some other beverage. After a debate that can last several minutes, we decide that we will settle for water. The waiter fires the next question: “Would you prefer bottled or plain water?” As we look at one another, rack our brains, discuss seriously and finally decide on one option, the next question is ready: “would you like cold, warm or room temperature water?” The moral of the story is, for such trivial matters, a decision taken without thinking is as good as a decision taken after a whole day’s deliberation.

Information overload kills

Information overload is an important cause of road accidents, as unfocused drivers check their mobile phones, texting, talking and even searching for directions while the vehicle is moving. Driving is a dynamic skill involving numerous micro-decisions being taken subconsciously every minute. Such distracting activities use up the brain’s limited resources, causing functional blindness and inattention, leading to accidents. This has been discussed in my earlier article on road accidents.

What are the solutions?

Information overload while driving can kill

Information overload while driving can kill

1. Information overload is for real: The first step is acknowledging the existence of the problem, and recognizing our vulnerability. If we remain unaware of it, information overload could consume us in the coming years, potentially reducing us to a state of permanent intellectual fatigue and inactivity.

2. One size doesn’t fit all: People are of varying tastes, personalities, backgrounds and professional interests. Information that is junk for one person might turn out to be useful to another. It pays to sit down and contemplate on our personal goals first and then decide what kind of information we are primarily interested to receive.

Those who don’t have clear personal goals will find it difficult to decide which information to take in or leave out. They fall victim to information overload.

Those who don’t have clear personal goals will find it difficult to decide which information to take in or leave out. They fall victim to information overload.

3. It isn’t information overload as much as ‘failure to filter’: Our inability to filter out material that is of no use to us is part of the problem. All information isn’t harmful. It is mostly the unsolicited information that needs to be filtered out.

4. Never underestimate the power of a nap: Taking a short 10-15 minute break, ‘quiet time’, a nutritious snack or even a power-nap (where feasible) during work will help refresh a clouded mind. Many reputed firms have built-in gyms and play areas where their employees can let off steam and recharge themselves for greater productivity.

5. What happens in office stays in office: Carrying office work home as well as carrying home work to the office is best avoided, although in certain professions ‘work from home’ is now standard. Leaving office problems at the office helps clear the mind when one reaches home, generating greater opportunity for quality time with family without being distracted.

6. Plan for tomorrow yesterday: Writing a simple ‘to do’ list the previous day evening is an amazingly effective way to start our day productively. Preparing the list beforehand will help avoid wasting our precious morning time in trying to decide on the day’s tasks. Information overload happens only later in the day, hence it is worth completing all the important bits during our peak efficiency hours.

The 80/20 rule helps boost efficiency at work - 80% of our good work is done during 20% of our time; it is just that we have to know our most productive time-window and keep it free from distraction.

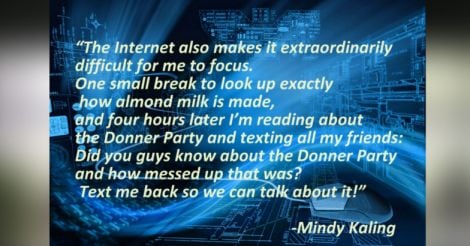

7. Silence is golden: Social media notifications are best kept turned off while at work, even otherwise. This gives us greater control of when we should access it. A single notification could distract us while trying to focus on a task, leading us down that familiar path of clicking, pondering, commenting and then moving on to other web-pages.

Quote by Mindy Kaling, comedian, about how social media can take anyone for a ride

Quote by Mindy Kaling, comedian, about how social media can take anyone for a ride

Keeping the mobile phone in silent mode is a useful practice for those who do focused work, such as doctors, lawyers and creative people. A periodic check for messages or missed calls in between appointments or during break time will be a lot more productive than getting interrupted every few minutes and struggling each time to regain focus and concentration.

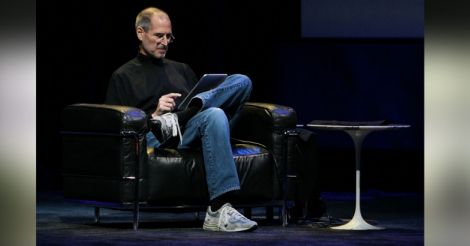

8. Don’t sweat the small stuff: It is best not to waste our brain’s resources for trivial decisions. Successful men have shown by example the importance they paid to avoiding such distractions. For example, Steve Jobs always wore a black T shirt and blue denim jeans because he did not want to waste his brain power by deciding what to wear at the start of each day.

Barack Obama wore only blue or gray suits for the same reason. "You'll see I wear only gray or blue suits," Obama said in an interview to Vanity Fair magazine. "I'm trying to pare down decisions. I don't want to make decisions about what I’m eating or wearing. Because I have too many other decisions to make."

While this is not an appeal to shed interest in one’s wardrobe or food choices, the principle is well-understood.

Steve Jobs always wore the same color as he didn’t want to waste his time everyday on making unimportant decisions such as choosing what color to wear

Steve Jobs always wore the same color as he didn’t want to waste his time everyday on making unimportant decisions such as choosing what color to wear

9. Strip the book down to the bone: Many non-fiction books contain a lot of ‘padding’ material, which is essentially words and sentences thrown in that do not add to the meaning. Such books often have a summary that is no longer than two paragraphs. The question is, is it worth reading 400 pages for two paragraphs of information?

10. Less is more: Those planning a lecture must first decide on the minimum effective dose (MED) of information they can deliver in the limited time given, and avoid the common mistake of compressing a one-hour lecture into a ten minute presentation. While at the receiving end of an overloaded lecture, scribbling a couple of main messages down will help us retain a minimum amount.

11. Keep it short: Apps like Inshorts and flipboard are getting popular by serving news in bite-sized portions, with an option to read more only if we are interested. Those who enjoy reading news on the Internet are now able to customize their apps or web portals according to their personal preferences. For example, Google news can be customized to selectively fetch articles from our favorite newspapers, on the topics and key words that we are interested in.

12. Less news is good news: One or two reliable sources of news are typically enough for most people, and that can be audio, visual, print or Internet-based. Keeping the TV on absentmindedly can open up the gates for information overload, at times turning our home into a virtual police control room - with relentless live reporting of crime, accidents, threats and scandals by TV channels claiming to show ‘breaking news’ each time. Knowing beforehand what program we want to watch will help avoid this deluge of disturbing negative information.

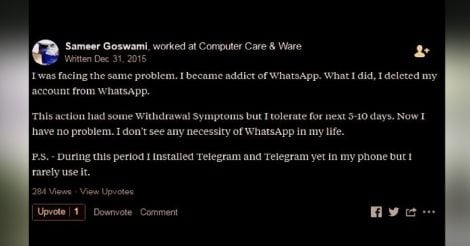

13. Social media can be addictive: Limiting the use of social media and email to only a few minutes once or twice a day is a smart way to retain control of our time. Those using Facebook can reduce the clutter on their walls by ‘unfollowing’ or ‘unfriending’ those contacts whose updates are offensive or uninteresting. This helps Facebook remain true to its original purpose: to help us stay in touch with friends worldwide without physically calling them up each time. Taking a periodic break from social media for one or two weeks is also helpful to regain focus on important tasks at hand.

The less we use it, the less we need it. How Sameer Goswami, 45, from Madhya Pradesh India, got rid of his social media addiction. (Reproduced with his permission)

The less we use it, the less we need it. How Sameer Goswami, 45, from Madhya Pradesh India, got rid of his social media addiction. (Reproduced with his permission)

In summary, information overload is part of modern lifestyle, and can affect us adversely unless we are able to filter out what we do not need. Too much information can lead to decision fatigue. Contrary to common belief, human beings are not good at multitasking, therefore it is wise to minimize distractions while at work or study. Making decisions about unimportant things can drain the brain’s energy. Setting limits on TV viewing, Internet and social media use will help reduce mind clutter and boost productivity. Keeping the brain well-nourished and well-rested is important to remain energetic and creative.

Further reading

1. Judges suffer decision fatigue after a long day

Up for Parole? Better Hope You’re First on the Docket

Extraneous factors in judicial decisions

2. Schadenfreude: why we secretly enjoy the misfortune of others

Why do we sometimes enjoy the misfortune of others?

3. How information overload can lower our IQ

4. How shoppers spend more money when hungry

Shopping while hungry? You could end up with a new TV

Hunger promotes acquisition of nonfood objects

5. How to customize Google news for your preferences

(The author is a senior consultant gastroenterologist and deputy medical director, Sunrise group of hospitals)