The most fascinating spectacle on a cricket field is the sight of a fast bowler in his delivery stride, when he approaches the bowling crease through a long run up, gradually building up pace and culminating in a leap just prior to the release of the hard red ball, which is hurled at great speed towards the batsman standing less than 22 yards away. The purveyors of this profession have invariably sought to overpower the willow-wielders into submission not merely by the velocity at which the balls are delivered, but also by the menace and aggression that radiates from every sinew of their bodies. History of cricket is replete with stories of fast bowlers who attained a larger than life image on account of their personalities, on and off the field. However, if any follower of the game is asked to name one fast bowler who symbolizes all the crafts of this trade, the chances are that, nine times out of ten, he would name Dennis Keith Lillee, the Australian speedster of the 1970s and early 80s.

Lillee was to Australian cricket fans of his times, what Sachin Tendulkar was to become to Indian cricket at the turn of the century. Inarguably one of the most popular fast bowlers of all times, Lillee symbolized Australian cricket of his era by his aggression, attitude, showmanship, determination and mastery over his craft. He was the very epitome of a fast bowler with a long run up, flowing mane, Mephistophelian moustache, classic bowling action and a style of appeal with the finger pointed right at the heart of the umpire, all intended to strike terror in the minds of the hapless batsman. Australian crowds loved him and would start chasing “Lillee Lillee”, each time he started walking back to the top of his bowling mark, with the chorus reaching a crescendo as the ball was released from his hand at top speed. It could be said confidently that no other fast bowler had captured the minds of the public in the manner that Lillee had done.

Tearaway to start with

Lillee started out as a tearaway fast bowler, whose only intention was to terrorize the batsmen by his sheer speed to get their wickets. He made his debut in Test cricket against England at Adelaide in 1971 and took five wickets for 84 runs in the very first innings that he bowled. However, his first brush with fame came when he destroyed a Rest of the World side comprising greats such as Gary Sobers, Rohan Kanhai, Sunil Gavaskar and Clive Lloyd by taking 8 for 29 in Perth a year later. Sobers has gone on record stating that this was the fastest spell of bowling that he faced in his entire career. When he took 32 wickets in five Tests during the Ashes series of 1972, played in England, it appeared that he was on the threshold of a great career. It was at this juncture that first of the many misfortunes, that has made the Lillee saga so unique, occurred.

Big blow

During the tour of West Indies in 1973, Lillee was laid low by persistent back pain which was so bad that he could not even bowl. It was subsequently diagnosed that his vertebrae had suffered stress fracture at three separate locations. Sports medicine had not developed as a separate faculty during those days nor had the practice of cricket boards subsidizing the medical treatment of cricketers started. In other words, Lillee was left to fend for himself and his promising career looked set for an early demise. Never the one to give up easily without a fight, Lillee spent six weeks in a plaster cast that covered his entire torso, following which he underwent extensive physiotherapy under Dr Frank Pyke at Perth. Dr Pyke was himself an accomplished sportsperson and he developed special set of exercises for strengthening the lower back muscles of the fast bowler that come under greater stress while bowling long spells. Under Dr Pyke’s supervision, Lillee also modified his bowling action and was soon back in the field at the start of 1974-75 season.

Dennis Lillee formed a lethal partnership with Jeff Thomson. File photo: Getty Images

Dennis Lillee formed a lethal partnership with Jeff Thomson. File photo: Getty Images England, who toured Australia in 1974-75 to retain the Ashes, was the unfortunate side that was fated to face Lillee who was coming back after injury, determined to prove himself. He struck a deadly combination with Jeff Thomson, one of the fastest bowlers of all time, and the two wreaked havoc taking 58 wickets between themselves in four Tests, with Lillee’s share being 25. This was followed by a tour of England in 1975 and a series against West Indies at home, where also the duo struck terror in the minds of opposing batmen helping Australia emerge easy winners. Lillee took 21 wickets against England while his tally against the Caribbeans was 27. The partnership with Thomson helped both bowlers as batsmen scarcely got a break from the thunderbolts released from either end. Further, while Thomson relied on sheer pace for bagging his victims, Lillee had become a more complete bowler, moving the ball both ways, cutting it sharply when the ball grew old and his armory included bouncers bowled at different speeds as well.

Straight-talker

Lillee developed a reputation for being a straight-talker who was unafraid to voice his views even against the establishment. He was the first to take up the issue of poor payments to players, which others were unwilling to raise for fear of annoying the authorities who ran the Australian Cricket Board (ACB). His words angered the establishment, but they were not able to do much about it given his popularity among the cricket lovers and performances on the field. However, this issue was capitalized by Kerry Packer, a media mogul,who devised an alternate cricket championship called World Series Cricket (WSC), in retaliation to the ACB, which had denied him the rights for telecasting cricket matches. The WSC proved to be a landmark event in the history of international cricket with top players of most countries, except India and to some extent England, preferring to play for Packer. The impasse ended only towards end of 1979 when the ACB backed down and gave television rights to Channel Nine, the company owned by Packer, following which WSC players returned to regular international cricket.

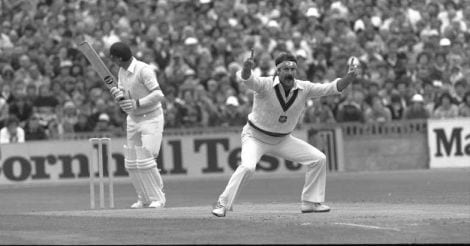

Dennis Lille had a style of his own while appealing. File photo: Getty Images

Dennis Lille had a style of his own while appealing. File photo: Getty ImagesThe last phase of Lillee’s career started after 1979. He continued to lead the Australian attack though he was nowhere near as fast as he was when he started out. However, his ability to make the ball behave exactly as he wished and the wide repertoire of deliveries at his command made him a dangerous opponent. His best bowling spell (seven wickets for 83 runs against West Indies) came during this period. During this match at the MCG in 1981, he also crossed the world record for maximum number of Test wickets, which was held by Lance Gibbs of West Indies (309). He continued playing till the end of 1983-84 and finished his last test with eight wickets, four in each innings, against Pakistan at the SCG.

Partnership with Rod Marsh

One partnership of Lillee that lasted all the way from first class cricket till his retirement from Test cricket was the one he enjoyed with Rodney Marsh, wicketkeeper of Western Australia provincial side and Australian national team. Marsh was without doubt one of the best wicketkeepers the game has seen and he forged a splendid understanding with Lillee, resulting in the entry 'caught Marsh bowled Lillee' figuring in scorecards of Test matches on 95 occasions. Marsh retired on the same day as Lillee, with both players co incidentally having the same number of Test match dismissals to their credit (355).

Infamous acts

No article about Lillee would be complete without mentioning two incidents that brought him lasting infamy. The first pertains to his attempt to use cricket bats made of aluminium in a Test match. To be fair to Lillee, he was technically not in the wrong as the laws governing the game at that point of time (December, 1979,) did not stipulate that bats should be made of wood. Lillee entered into a agreement with manufacturer of aluminium bats and walked in to bat during the first Test of the series against England in 1979-80 with one such bat in hand.

After he had faced couple of deliveries, Mike Brearley, captain of England complained to umpires that ball was getting damaged due to it being struck by aluminium bat. This forced the umpires to ask Lillee to use a bat made out of wood, which he accepted only after considerable persuasion and with much reluctance, which he demonstrated by throwing the bat. This was big publicity for the makers of aluminium bat, but unfortunately this incident led to amendments to the Laws of Cricket, making it mandatory that bats should be made of conventional willow.

The second episode took place during the first Test against Pakistan at Perth in November, 1981. Needing a near impossible 543 to win, the visitors were reduced to 27 for 2, when Javed Miandad, then leading Pakistan, arrived at the crease. He and Mansoor Akhtar slowly repaired the damage and were getting into their stride when Miandad turned one ball from Lillee to behind square leg. Miandad completed one run and as he turned back for the second, there was a scuffle between him and the bowler. The exact sequence of events will never be known as both players blamed each other for what happened. Miandad said that Lillee deliberately moved in his path and obstructed him, which made him push the bowler away using his bat. Lillee maintained that Miandad swore at him and hit him from behind with the bat while completing the first run, which prompted him to retaliate. Umpire Tony Crafter had to physically place himself between a wild-eyed Lillee, who looked ready for some fisticuffs, and Miandad, who had raised his bat like a mace, to prevent further damage. The pictures of this unedifying spectacle made headlines and the actions of players invited all-round criticism. Though Lillee maintained his innocence, he was suspended by ACB for two limited overs matches and imposed a small fine, while Miandad got away without any penalty.

Dennis Lillee and Javed Miandad almost came to blows during the 1981 Perth Test. File photo: Getty Images

Dennis Lillee and Javed Miandad almost came to blows during the 1981 Perth Test. File photo: Getty ImagesAfter his retirement from the game, Lillee chose to become a fast bowling coach, spending most of his time with the MRF Pace Foundation in India, a country where he had not played Test cricket. He brought the best and latest techniques in coaching and physical training to aspiring fast bowlers in India through the MRF Pace Foundation, which has produced many international players. His inputs and guidance have helped shape the career of many a fast bowler in India, a land that was almost barren when it came to producing quick bowlers.

Lillee continues to figure in television advertisements in Australia more than three decades after his retirement. He was among the first to be signed up by Channel Nine, in 1977, to work as a commentator but he chose to stay away from media and the commentary box after retiring from the game. Though he was known to be outspoken during his playing days he has not courted any controversy after he hung up his boots. Despite this and the advancing age, which has left more hair under his nose than on his scalp, he continues to be a mobbed by fans wherever he goes in any country that plays cricket.

This leads one to ask the question as to what constitutes the Lillee magic. There have been bowlers who hurled the cricket ball faster than he did; his records on the playing fields have all been broken long back; yet Lillee continues to remain one of the most influential and inspirational cricketers ever. His bowling stride invariably adorns all the books on the subject of fast bowling even today, despite the passage of so many years after his playing days. This is because his deeds as a sportsperson who refused to bow down before any challenge, whether caused by injury or otherwise, however difficult they were, continue to inspire young cricketers world over. He embodied all the virtues of a true fighter, a player whose never-say-die attitude moved mountains and helped him attain greatness.

(The author is a former international umpire and a senior bureaucrat)

Dennis Lillee had a classical bowling action. File photo: Getty Images

Dennis Lillee had a classical bowling action. File photo: Getty Images