In the days before helmets and other protective equipment became a part of cricketing gear, physical courage was as much a requirement as correct technique for becoming a successful batsman. It required courage bordering on madness to stand up and face fast bowlers capable of hurling a cricket ball at speeds touching 90 to 100 miles per hour, knowing with certainty that even the smallest of errors of judgment would result in resetting of one’s facial architecture or worse.

The physical pain that a cricket ball can cause when it strikes human body cannot be described in mere words; suffice to say that it would rank alongside administration of electric shocks and whippings, both with regard to the intensity of the pain and the emotional trauma that follows the incident. Players who have been struck once would find the need to exorcise many a mental ghost before being able to come back to the crease and take guard again. Cricket history is replete with stories of many a talented batsman who fell by the way side, not on account of being found wanting in technique or temperament, but for not possessing the courage to take on bowlers sending down thunderbolts aimed at their body.

Courageous Close

Brian Close, the former captain of England, who passed away in September, 2015, would rank as the most courageous cricketer ever in the minds of those who followed the game through the 1960s to 1980s. Close had an unremarkable career in international cricket, despite starting off as the youngest England player to make his Test debut, scoring less than 900 runs in the 18 Tests that he played. However, what made him stand apart from the other players of his generations was the raw courage that he demonstrated while taking on the fast bowlers, especially those hailing from the West Indies. In the Lord’s Test in 1966, he took on Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith, bowling at their quickest, by coming down the pitch and repeatedly taking blows on his body. His fighting innings ensured that England managed to save the Test.

Ten years later, when the West Indies toured England in 1976, Close was recalled to the side at the age of 45 and asked to open the innings after the first two Tests. When he asked from his captain Tony Greig the reasons for being chosen for this task, he got the reply that the team management did not want the regular opener Bob Woolmer to be killed! Close took up the challenge and, on a nasty wicket at Old Trafford, kept Andy Roberts and Micheal Holding at bay for more than two hours. Unfortunately, the rest of the side could not follow the example set by this elder statesman who knew no fear, and England collapsed like a pack of cards in both innings.

The newspapers of the day carried photos of Close sitting in the dressing room after the Test with his torso showing seven huge bruises where the ball had struck him during his brave forays to the wicket. While fielding also, Close chose the position closest to the bat at short leg where he picked up some brilliant catches. He did not indulge in sledging like the cricketers of modern era, but his daunting presence so near their feet had a huge psychological impact on the batsmen and made them commit mistakes.

Close was asked later on how he managed to stay at the crease and take on the fast bowlers after being repeatedly hit on the body; the interviewer wanted to know whether his pain threshold was higher than others. The reply given, in addition to being a master understatement, also speaks volumes about the strength of his mind and character. He said: “I was never scared of a cricket ball; I was just doing a job; my job was to get behind the line of the ball. I bruised the same way as everyone else; the only trouble is I do not worry about it.” It is no wonder that his onetime adversary Holding said on hearing about his death, “Close was not just the toughest batsman, he was one of the toughest people around in the game”.

Nayudu leads from the front

It would be interesting to see how Indian batsmen fared during the pre-helmet period when it came to demonstrating physical courage. Indian cricket had the good fortune that their first ever Test captain, Col. C. K. Nayudu was also one of the most courageous of batsmen. During the Test match at the Oval in 1936, Nayudu was hit on his chest by English speedster Gubby Allen. The sound of the blow was described by of the correspondents who covered the match “as a sickening one which could be heard all around the ground”. Nayudu sunk to his haunches, but got up soon and continued batting to score 81, repeatedly hooking and pulling Allen to the boundary whenever he pitched short. Much later, when he was past the age of 50, Nayudu was struck on his face by a bouncer from Dattu Phadkar, while playing in a Ranji Trophy match. Nayudu stood his ground, spat out blood and a couple of teeth, which he swept away from the pitch with his bat and took strike to face the next ball, even as the fielding side looked on worriedly, scared even to approach the great man and offer help. Phadkar, who was shaken by this episode, sent down a full toss in remorse and Nayudu duly hit it to the boundary, chiding the bowler for sending a bad delivery!

However, Indian batsmen developed a reputation for being scared of fast bowling during the 1950s and 1960s. This disrepute was brought on by a couple of instances where leading batsmen backed away from the line of the ball while facing fast bowlers on difficult tracks. This was reversed only during the 1970s after Sunil Gavaskar and Gundappa Viswanath arrived on the scene and showed that they were second to none when it came to possessing the courage and technique for facing fast bowlers indulging in intimidatory tactics. Australian players developed a healthy respect for Sandip Patil after he scored a blistering 174 in the second Test at Adelaide after being struck by a bouncer by Len Pascoe in the first match of the series in 1980-81. Mohinder Amarnath was another Indian batsman who displayed tremendous courage while facing fast bowlers. During the Test match at Barbados in 1983, on a nasty wicket, he kept on hooking West Indies pace bowlers who were bowling at their fastest and meanest to score 91 and 80. He was forced to retire after being struck on the face, but resumed his innings at the fall of another wicket and kept on batting in the same vein. Immense courage was also displayed by Eknath Solkar who fielded close to the bat at short leg and picked up many brilliant catches, thus lending an extra edge to the spin bowlers. India started winning Test matches abroad on a regular basis only after these players removed the stigma associated with Indians as ones lacking in grit and physical courage.

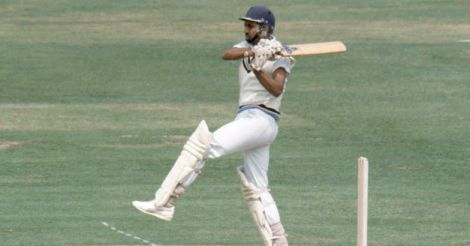

Mohinder Amarnath was never afraid to take on the fast bowlers. Getty Images

Mohinder Amarnath was never afraid to take on the fast bowlers. Getty ImagesHow would one compare the players of the yore with those of the present generation in the aspect of fearlessness on cricket field? It would not be a fair assessment as modern protective gears have ensured that, except in extremely rare cases, the possibility of physical injury and pain have been minimized. The cases of Phil Hughes, who died after being struck on the head by a bouncer despite wearing a helmet, and Raman Lamba, who succumbed to brain damage consequent to injury suffered while fielding close to the wicket without wearing one, are exceptions. The restriction on bouncers, the strict rules on maintenance of over rates, emergence of neutral umpires and enforcement of generally uniform playing conditions have combined to neutralize the advantages that fast bowlers used to enjoy earlier. However, when one see sights like a young Sachin Tendulkar choosing to continue to bat after being hit in his chin by a Waqar Younis bouncer in his debut series in Pakistan or Anil Kumble coming out to bowl against the West Indies with his fractured jaw strapped, one knows that physical courage has not gone out of fashion completely.

Unique charm

It would be a shame if the elements of fear and uncertainty are eliminated from cricket altogether. While the unpredictability associated with a sporting event lends it a unique charm, physical courage and strength of character are the elements that separate the men from the boys and the performers from the also-rans. There is no sight more exciting on a cricket field than a batsman hooking a bouncer hurled at him at speeds in the range of 140-150 kilometers per hour. The thrill associated with grabbing a sharp catch close to the wicket is unique to this game and needs to be preserved. True champions never shy away from challenges posed by fear of physical pain nor would they be daunted by attempts at intimidation.

Cricket would always remain a hard game played hard using a hard ball. The excitement in any sporting event increases in direct proportion to the challenges involved. The risk of physical injury while in action on the field poses the greatest threat to any sportsperson and prompts him to higher performance levels. The exploits of the brave cricketers who had defied fear of physical injury and taken the game to higher levels would be remembered forever by the lovers of the game.

(The author is a former international umpire and a senior bureaucrat)

Read also: More from Vantage Point | Kuldeep - a rare talent

Brian Close takes a Michael Holding bouncer on his chest during the Old Trafford Test of 1976. Getty Images

Brian Close takes a Michael Holding bouncer on his chest during the Old Trafford Test of 1976. Getty Images