"On the 26th of January 1950, we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics, we will have equality and in social and economic life we will have inequality."

B.R. Ambedkar

As the nation welcomes Mr Ram Nath Kovind as its next president, the dalit question confronts us straight in the face. By fielding a dalit candidate each, both fronts had ensured that the nation gets a dalit as its next Head of State and first citizen. Only once before has this happened (K.R. Narayanan,1997-2002) in our seven-decade history. While the symbolic significance of such an appointment is huge, we also need to ask whether it does any real good to the cause of social justice.

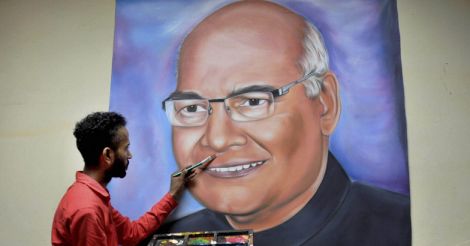

An artist gives final touches to a portrait of president-elect Ram Nath Kovind.

An artist gives final touches to a portrait of president-elect Ram Nath Kovind. In his masterpiece, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (1979), Pierre Bourdieu, the great French sociologist, talks about four kinds of capital: financial, social, cultural and symbolic. Every individual makes use of these four (in varying degrees, of course) for survival as well as progress. However, in India, the dalit population have historically been denied access to, let alone possession of, any form of capital by the dominant communities. That a horrible practice such as the caste system had the sanction of religion as well as the backing of tradition made it all the more difficult to be resisted.

It was only when Ambedkar took up the cause did this become a national issue. During the Independence struggle, when Gandhiji suggested that the dalit agitation be withheld for a while so that all the people can fight unitedly for the freedom of our homeland, Ambedkar famously retorted, "Bapu, I have no homeland."

Seventy years after independence, the Dalit still languishes at the foot of the social ladder. Quite like how Martin Luther King Jr described the status of the black American even after a century of the Emancipation proclamation. In the historic address of 1963 during 'the March on Washington' (better known as the 'I Have a Dream' speech) he reminded the massive gathering that "one hundred years later," the black American "lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst a vast ocean of material prosperity" and "is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land."

Even today in India, there are very few dalit faces among the top leadership of all political parties. In fact, a dalit politician is usually given a seat to contest only in the reserved category.

There are very few dalit faces in the top rung of the media -- both print and visual. They are similarly absent (or too few and far between) in decision-making capacities of most professions or fields that can directly affect the society.

The root cause of this terrible inequality is the consistent denial of access to resources all through history. The only redressal mechanism available now is the reservation policy but even that is strongly resisted by a large section of the population for understandable but unjustifiable reasons.

Instead of addressing these fundamental issues, what political parties often do is indulge in tokenism. As if, some symbolic gesture will take care of the problem. Once in a long while, they will choose a dalit as president, speaker or governor. But they make sure that the candidate is not someone who is identified with (and therefore vocal about) the dalit cause. Often it's someone who does not appear 'threatening' to the public consciousness (which is the same as the dominant sensibility).

This kind of tokenism (in the name of social justice) is extended to other causes too. Take the case of gender, for instance. Indira Gandhi became president of the Congress party and later prime minister, only because she happened to be Jawaharlal Nehru's only child. Years later, the same family tag also helped an Italian lady get to the former position easily and almost to the latter office as well. Otherwise, women are kept out of reckoning while choosing occupants to the highest offices, both in the party and the government. Strong willed women like Jayalalithaa and Mamata Banerjee had to come out of the patriarchal fold and break their own paths.

Indira Gandhi

Indira GandhiIf an exception is made, it is usually for someone whom patriarchy (or whichever dominant ideology) considers its own. Sometimes, communal considerations too (Muslim, Sikh etc) are dictated either by an appeal to the public consciousness or to the will of the supreme leader. Thus A.P.J. Abdul Kalam was this 'good' Muslim of Hindutva, while Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, Giani Zail Singh and Pratibha Patil were the 'loyal devotees' of the political majesty.

The first three presidents India got after becoming a Republic were men of undisputed integrity and credibility, just like our first two prime ministers. But during Indira Gandhi's regime, the ethical and democratic foundations of our polity got weakened. She who declared the Emergency had already installed a weakling as president who had no qualms in signing the ordinance.

We cannot deny the symbolic significance in the appointment of a dalit (or woman, Muslim) as president. The confidence, hope, and self-respect it offers to the respective community are tremendous. And for that very reason, we should welcome any number of such appointments. But it will remain a meaningless token as long as the majority of that community do not experience any of those feelings or even a sense of belonging to the larger society. This is precisely the contradiction (between the political life and the socioeconomic life) that Ambedkar talked about.

Will a dalit ever become the supreme leader of either the Congress or the BJP? Will India ever get a dalit prime minister? If and when that happens, perhaps we can claim that we, as a nation, are serious about social justice.

(The author is associate professor in the department of English at St Berchmans' College, Changanassery. A bilingual writer, public speaker and translator, he is an active presence in the academic circles of Kerala. Views are personal.)

Read more: Columns | Critical Soliloquies

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar