"Cricket is an Indian game accidentally discovered by the British." -- Ashis Nandy, The Tao of Cricket

As India and Pakistan meet for the title clash of this year's ICC Champions Trophy (18 June, The Oval, London), it's interesting to reflect on cricket's colonial history as well as what the game means to the people of the subcontinent. Many were reminded of this historical connection recently when the line-up for the semi-finals was drawn with England and three of its former colonies making it to the last round. That Bangladesh was not an independent entity when the British were around does not make any difference to the reality. And the social media was quick in responding with jokes and comments.

Cricket, it has been pointed out, was a clever means devised by the Englishmen to get out of their cold houses and into the sun ('the flannelled fools' is Kipling's phrase). Later, they took the game wherever they went and impressed everyone (except the Americans, who after playing it seriously in the 19th century, happily returned to Baseball, their kind of 'bat and ball' game).

By the same author: The ministry of happiness and provocation

After the English language, perhaps it's cricket that is the most decisive legacy of British colonialism to the world. The game is played with great passion all over (and only in) the former Empire and a certain psychological urge to excel in 'his Master's sport' is evident in every player there.

The other day, when the Pakistani captain, with his shaky English, struggled to answer the questions put to him during a post-match press conference, the British media had great fun at his expense. Little did they realize that within a couple of days they would have to face him again after his side thrashing the English team thoroughly. Caliban the native, in Shakespeare's The Tempest, tells Prospero the colonizer: "You taught me language, and my profit on it is, I know how to curse."

Well, had they played cricket, Caliban would have loved to bowl Prospero out for a golden duck or knock him on the helmet with a deadly bouncer. Or if he's holding a bat, hit sixes of all six balls of an over, just as our Yuvraj (ideal name) did to an English fast bowler a few years ago. Doesn't that qualify for a case of the Empire hitting back?

Read: In-depth coverage of Champions Trophy 2017

Pakistan's never-say-die attitude to the fore yet again

Sachin: A Billion Dreams review - bowled over yet again

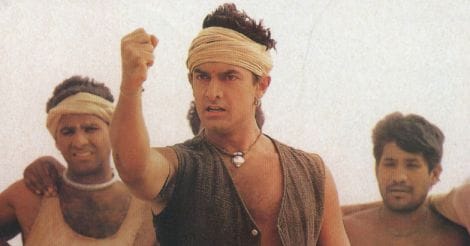

Aamir Khan's Lagaan broke all collection records, not because it was a great movie, but because the Indians loved its argument as well as the curious mix of cricket, cinema and nationalism.

Aamir Khan in 'Lagaan' (2001)

Aamir Khan in 'Lagaan' (2001)And talking about the nation, I think everyone will agree that right now in India there's nothing like cricket that can bring people together. Everything else -- politics, movies or music -- has a strong regional bias, but cricket alone is a unifying factor. While in England or Australia people merely watch a match, here they celebrate it. (Or is it more like the Christians partaking of or celebrating the Mass?)

If cricket is our religion, then Sachin Tendulkar must be its presiding deity. Of course there have been other heroes before and after him (Sunil Gavaskar and Kapil Dev earlier, MS Dhoni and Virat Kohli now), but nobody else is likely to dominate the mindscape of millions the way Sachin did for more than two decades. Even if Kohli (or another younger player) breaks all batting records, even if he proves to be a better player than the Master, it's doubtful whether the new generation will feel what an earlier generation did for Sachin. It's not about the person or talent alone but also about the milieu as well as the time. Sachin's romance with the nation's collective imagination was unique. He's to cricket what Mahatma Gandhi was to our politics. A phenomenon that happens only once in (and at a critical point of) a nation's lifetime. Many years ago, Tarun Tejpal analyzed this romance in an essay for Outlook. I was so fascinated by the brilliance and beauty of his sentences (this was much before Shashi Tharoor began to claim that honor) that I copied some of them on a notebook:

Sachin Tendulkar during a match in 2014. Getty Images

Sachin Tendulkar during a match in 2014. Getty Images"Much before Sachin commences strapping on his armour, a nation begins to prepare. Across the dispirited homes and listless offices, a strange frisson starts to course. The frisson has a hormonal edge....In pulsating minutes a sublime duet will be set in motion, it will play between the puissant boy-emperor and his loyal subjects."

This kind of loyalty was possible only because he was the best in the world and thereby offered a not-very-confident people something to feel proud about. The implication of a short, little Indian dominating the fierce attack of well-built and white-skinned bowlers all around the world transgressed the sporting arena and entered the realms of politics, history and psychology. As C.L. R. James famously asked in his masterpiece Beyond A Boundary (arguably, the most important book ever written on cricket): "What do they know of cricket who only cricket know?"

Cricket was a means for peripheral nations like the West Indies to write themselves into history, to stand up to the masters at the center. This is exactly what Donald Bradman did for the Australians as well. Though they too were white and of European descent, the people of Australia couldn't claim any distinct honor or superiority as a nation, until Bradman came along. As Thomas Keneally, one of their finest writers (best known for the Booker winning Schindler's Ark that Stephen Spielberg converted to a great movie) puts it: "In the manner in which soccer is the great way up for the children from the economic sumps of Brazil, so cricket was the great way out of Australian cultural ignominy. No Australian had written Paradise Lost, but Bradman had made a hundred before lunch at Lord's."

When Kapil Dev lifted the World Cup in 1983, or Sunil Gavaskar became the first batsman to reach 10,000 Test runs, or Saurav Ganguly pulled off his shirt and waved it from the hallowed balcony of the Lord's (along with a nice English expression repeated a few times), it was more than just about a game between two teams. Rather, these were statements made by a wounded nation asserting itself to the rest of the world.

Kapil Dev receives the Prudential Cricket World Cup from the Prudential managing director at Lord's in 1983. Getty Images

Kapil Dev receives the Prudential Cricket World Cup from the Prudential managing director at Lord's in 1983. Getty ImagesEvery time a predominantly brown/black team plays against a predominantly white team, the colonial undercurrent of history is evoked. However, in the last decade or so, the need for self-assertion isn't felt that keenly by India. A team led by MS Dhoni or (even lesser for) Virat Kohli doesn't have to prove anything to anybody. India has already arrived and has made it big among the cricket playing nations. Our nation as well as the cricket board has grown so strong economically that we have already become the world's most important place for cricket. Also, with the white/Christian teams changing colors increasingly (pun intended), with more brown/black/Muslim players in the ranks, the cultural/political equation has changed drastically. Hashim Amla is today the backbone of South African batting, but when he began his career, his appearance mattered more than the performance (Dean Jones lost his commentating career for several years for saying something stupid and insensitive about it). That has changed (certainly for the better) and it's all about multiculturalism today.

Hashim Amla during an IPL T20 match

Hashim Amla during an IPL T20 matchIndia, Pakistan and Bangladesh were one big piece of land until the British came. They gave us English and cricket. Today we have more speakers of English in India alone than the entire population of England. Similarly, cricket in England is nothing today compared to what it is in the three nations. Whenever India meets either Pakistan or Bangladesh in England, the crowd turns decisively Asian, so much so that we really wonder whether the game is played in the Eden Gardens or the Wankhede. And this Sunday's final will once again prove the validity of Ashis Nandy's argument.

I will wind up with an adaptation of a fine post-colonial joke about the native African complaining that "when the white man came, he had the Bible and we had our lands. Now we have the Bible and he has all the land." When the Englishman came to the Indian subcontinent, he brought English and cricket, while we had our lands. He held all three for a while. Now we have all three, just that the land has been splintered into three, with a lot of blood spilling in the process. There's no greater rivalry in the world than between siblings (and in this case, representing a billion and a half people with such a problematic past that informs an equally problematic present).

India players celebrate with the trophy after India defeated Sri Lanka a in the 2011 ICC World Cup final at Wankhede Stadium on April 2, 2011 in Mumbai. Getty Images

India players celebrate with the trophy after India defeated Sri Lanka a in the 2011 ICC World Cup final at Wankhede Stadium on April 2, 2011 in Mumbai. Getty ImagesAnd here's an unusual display of that rivalry played out in the form of the colonial master's game and that too on his soil. Of course, it's still a game of cricket, but the fierce eyes of history stare at us.

(The author is associate professor in the department of English at St Berchmans' College, Changanassery. His areas of expertise include Shakespeare Studies, Literary Theory and Cultural Studies. A bilingual writer, public speaker and translator, he is an active presence in the academic circles of Kerala.)

India captain Virat Kohli and Pakistan captain Sarfraz Ahmed hold the ICC Champions Trophy ahead of Sunday's final at The Kia Oval in London, England. Getty Images

India captain Virat Kohli and Pakistan captain Sarfraz Ahmed hold the ICC Champions Trophy ahead of Sunday's final at The Kia Oval in London, England. Getty Images