No family has perhaps received as much attention as the cholesterol family, whose members are commonly discussed in almost every forum - social, academic or otherwise. We often hear about LDL, VLDL, HDL and catchy terms such as ‘good cholesterol’, ‘bad cholesterol’ while discussing health or while looking at lab reports. Cholesterol is a buzzword familiar even to children studying in first grade. The internet and media are flooded with advertisements that promise to reduce cholesterol.

Together, the terms VLDL, LDL and HDL can be called the cholesterol family. Understanding cholesterol requires an explanation of relevant biochemistry and cell biology, without which discussions become superficial. This article starts with the basics and then takes the reader into the delicious depths of science, and concludes with a list of heart-healthy lifestyle choices. A glossary of technical terms is also included.

There is no good or bad:

The first thing to acknowledge is that there is no ‘good’ or ‘bad’ cholesterol. It is all the same cholesterol that is present in each of these three components. However, each particle has a distinct role in the body, and contains different proportions of cholesterol, triglycerides and other molecules.

To make interpretation of lipid profile easy, HDL cholesterol is sometimes called ‘good cholesterol’ as higher levels are associated with lower chance of heart disease. Likewise, LDL Cholesterol is frequently called ‘bad cholesterol’ because the opposite is true - higher LDL levels are traditionally linked with greater risk of heart disease.

It must be remembered that in medical research, ‘association’ does not always imply ‘causation’ and that knowledge in this field is still evolving. At this time, the exact cause of coronary artery disease is still unclear, although several risk factors are identified - an unfavourable lipid profile being just one among them.

What is LDL and HDL?

LDL stands for Low Density Lipoprotein. It is a carrier of cholesterol in the blood stream, and its job is to transport cholesterol from the liver into the tissues.

HDL is short for High Density Lipoprotein. Its job is to fetch any excess cholesterol from tissues and bring it back to the liver for disposal.

The Cholesterol family: the largest of the family is the chylomicron, followed by VLDL, IDL, LDL and HDL. Lipoproteins are basically carrier vehicles that ferry water-insoluble fats and cholesterol from areas of production to areas of need.

The Cholesterol family: the largest of the family is the chylomicron, followed by VLDL, IDL, LDL and HDL. Lipoproteins are basically carrier vehicles that ferry water-insoluble fats and cholesterol from areas of production to areas of need.A lipoprotein is a specialised spherical particle that has a water-friendly outer coat made of phospholipids and proteins, enclosing a storage hold – a waterproof core where cholesterol and fat are kept safe until the delivery point is reached.

What is Cholesterol?

Cholesterol is an essential ingredient of our cell membrane, and is the basic template from which several hormones are made. Our nervous system contains large amounts of cholesterol – in fact the brain is the most cholesterol-rich organ in the body. Almost exclusively an animal product, cholesterol’s role in the cell membrane is so intricate that it borders on the magical.

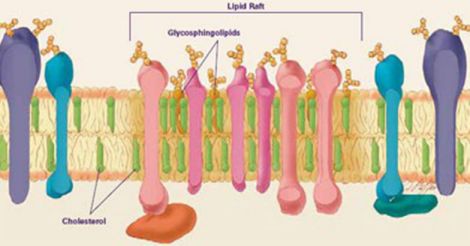

The cell is the basic unit of our body, and is almost an entire organism in itself. It contains tiny organelles that have specialised jobs, each enclosed in its own membrane. Composed mostly of fat, cholesterol and some protein, the cell membrane has tiny channels that allow only selected molecules to pass through. It displays receptors for hormones to act upon, recognises and thwarts attacks from harmful germs and adapts constantly to the daily requirements of the body.

Cholesterol is vital for the integrity and fluidity of the cell membrane, and also forms special portals called lipid rafts within the membrane - which have a role in intercellular communication.

Cholesterol is a part of our cell membrane: the complex structure of our cell membrane, which is made mostly of cholesterol and fat, with protein molecules embedded in it. Lipid rafts are areas within the membrane that have multiple roles - particularly in the communications department.

Cholesterol is a part of our cell membrane: the complex structure of our cell membrane, which is made mostly of cholesterol and fat, with protein molecules embedded in it. Lipid rafts are areas within the membrane that have multiple roles - particularly in the communications department.

The cholesterol manufacturing process in itself is elaborate, involving numerous enzymes and intermediate molecules that inter-connect several biochemical pathways in the body. As it is such a vital ingredient, our body has the ability to produce cholesterol from assorted raw materials such as fatty acids, glucose, fructose and even proteins, all of which contribute to the production of acetyl CoA, the basic platform for cholesterol synthesis.

The cholesterol molecule is a waxy substance, and does not dissolve in water. Blood happens to be the body’s chief transport medium, and is mostly composed of water – which means that waxy substances like cholesterol cannot travel freely in it. Therefore, to be carried in blood, cholesterol needs to be loaded into certain carrier particles called lipoproteins. These are water-miscible and carry cholesterol safely to sites of use – almost like pickup trucks transporting freshly made bricks from the factory to construction sites.

Most of the cholesterol in circulation is in the form of esters, which means that the cholesterol is combined with a fatty acid - so that it can be stored safely inside the waterproof cargo hold of the lipoprotein carrier particle.

Where does the cholesterol in the blood come from?

Most of the circulating blood cholesterol was made in the liver, though practically every cell in the body has the ability to make some of its own. Once produced, cholesterol needs to be shipped to areas of need. This is done through lipoproteins including VLDL, LDL and IDL.

Some cholesterol is present in blood as HDL-C, which is essentially recycled cholesterol picked up from tissues and is on its way back to the liver.

A small portion of the cholesterol in blood came from the gut after absorption. The absorbed cholesterol from the intestine is ferried in large boats called chylomicrons, which sail slowly though the lymph and blood, delivering freshly absorbed fat and cholesterol to tissues. Once their work is done, the shrivelled-up chylomicrons are swallowed by the liver and recycled.

What are triglycerides?

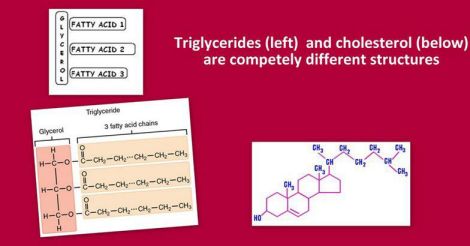

The lipid profile also reports triglyceride levels, which is a measure of how much fat is in circulation. Higher levels are seen in obesity, diabetes, dietary indiscretion and excess alcohol use. Biochemically speaking, triglyceride is the basic unit of fat, and has three fatty acids with long carbon chains attached to a stalk of glycerol.

Cholesterol and triglyceride are completely different entities both in structure and function. Cholesterol is a sterol with four hydrocarbon rings and used for construction, while triglycerides are either broken down and used for energy or stored for later use.

After a meal, the blood triglyceride levels peak due to the presence of chylomicrons bringing fat from the gut. In fact, after a fatty meal, the normally transparent plasma turns a milky white colour – also called lipemic serum - from this surge of chylomicrons.

In a fasting state, as the chylomicrons are gone, most of the circulating triglyceride is found inside VLDL particles.

Triglycerides are the basic unit of fat in diet. They are made of three fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule. Cholesterol is an entirely different compound- a sterol with four hydrocarbon rings.

Triglycerides are the basic unit of fat in diet. They are made of three fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule. Cholesterol is an entirely different compound- a sterol with four hydrocarbon rings.What is the fate of the cholesterol that gets shipped out of the liver?

After production, the liver ships cholesterol out through VLDL, a carrier particle. The VLDL is dispatched from the liver with five portions of triglyceride for one portion of cholesterol packed in its cargo hold.

As the VLDL travels through blood like a bulky courier truck, it delivers its cargo to areas where each component is needed. The triglyceride (fat) gets dumped into adipose tissue, where it is stored as a fuel source. The cholesterol is taken up by cells for building cell membranes as well as hormones.

As the VLDL continues its journey, it gives up a lot of the fat. As a result, the particle becomes smaller, but more dense. It is now called IDL or intermediate density lipoprotein.

As the IDL travels further and all of the remaining fat gets delivered to tissues, only cholesterol and some phospholipids remain in its cargo hold. Being smaller than IDL, it now gains the name LDL or low-density lipoprotein.

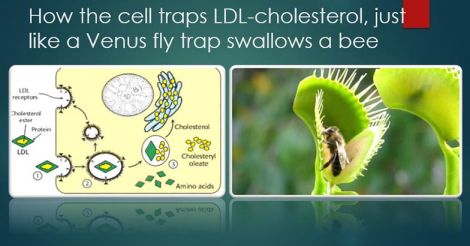

LDL contains mostly cholesterol. As it travels around, like a bee carrying pollen and looking for honey, it searches for and attaches to LDL receptors that get displayed on cell membranes.

When a cell wants more cholesterol than it can produce on its own, it flags down a passing LDL particle. For this, the cell first displays an LDL receptor on its membrane, and this attracts circulating LDL. As the LDL attaches to the receptor, it gets swallowed by the cell which extracts the cholesterol and then recycles the receptor for future use.

Once inside the cell, the cholesterol, which originally was in the ester form, gets hydrolysed by an enzyme, releasing free cholesterol into the cytoplasm. The cell may use this cholesterol to build its membrane or to synthesise hormones. Any excess remaining after use is either stored by converting back to cholesterol ester, or dispatched back to the liver through HDL.

Fascinating biology: how the cell receives cholesterol brought in by LDL. In a dramatic process called endocytosis, the cell swallows the LDL particle that comes and attaches to the LDL receptor, almost like how a bee settles on the carnivorous Venus Flytrap plant, gets swallowed and then digested.

Fascinating biology: how the cell receives cholesterol brought in by LDL. In a dramatic process called endocytosis, the cell swallows the LDL particle that comes and attaches to the LDL receptor, almost like how a bee settles on the carnivorous Venus Flytrap plant, gets swallowed and then digested.

What is the role of HDL?

HDL is a lipoprotein carrier made by the liver and intestine. Its main purpose is believed to be reverse cholesterol transport – that is to soak up excess cholesterol from tissues and return it to the liver.

The HDL particle carries an enzyme called LCAT on its surface. This converts any free cholesterol it encounters into the heavier ester form, which promptly finds its way to the waterproof core of the HDL particle. As the surface concentration of free cholesterol falls, a gradient is established and the HDL particle is able to take up more free cholesterol from tissue - like a sponge that is always dry on the outside. As it does this repeatedly, the HDL particle gets larger just as a leech swells up while it sucks blood. The fate of the HDL particle is to be eventually swallowed by the liver.

Although higher levels of HDL are considered ‘protective’ against heart disease, recent trials attempting to further increase HDL levels failed, and had to be halted because such medications caused more cardiac deaths.

The results of these trials show that our knowledge of cholesterol and heart disease is far from complete, and may involve a lot more variables and processes than are currently known.

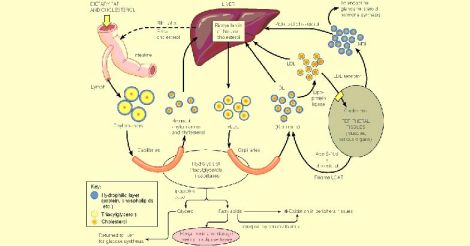

The journey of cholesterol. the various members of the cholesterol family can be seen in the picture: Chylomicrons that carry cholesterol from the gut, HDL that brings cholesterol back into the liver, VLDL that ships cholesterol out of the liver and its eventual transformation into LDL. The picture also shows how the peripheral tissues (shown in grey) handle cholesterol.

The journey of cholesterol. the various members of the cholesterol family can be seen in the picture: Chylomicrons that carry cholesterol from the gut, HDL that brings cholesterol back into the liver, VLDL that ships cholesterol out of the liver and its eventual transformation into LDL. The picture also shows how the peripheral tissues (shown in grey) handle cholesterol.Why is LDL cholesterol considered ‘bad cholesterol’?

Studies have consistently shown that higher LDL-C levels correlate with heart disease, and that reducing LDL levels through lifestyle measures or medications reduced the risk of future cardiac events.

The mechanism by which LDL cholesterol is linked with heart disease is not clear. The presence of oxidised LDL in the walls of coronary arteries is believed to attract the attention of inflammatory cells (defence system) which leads on to atherosclerosis or inflammation and hardening of the arteries, causing blockage of blood flow to heart muscle.

While the above theory sounds plausible, there is lack of clarity about the exact sequence of events that leads to the narrowing of coronary arteries. It is established that inflammation within the walls of the artery is the key factor, and science is still searching for all the factors that cause this inflammation.

How does the body naturally maintain cholesterol level?

Cholesterol is an important life-sustaining molecule. Hence, each cell in our body possesses the ability not only to manufacture it internally, but also to receive extra supplies from outside. Cells can boost their own cholesterol supply by flagging down circulating lipoprotein carriers like LDL. They can also signal the gut to absorb more cholesterol.

The body has its own multipronged strategies of maintaining cholesterol at a healthy level. This involves the orchestrated performance of dozens of genes, enzymes, elaborate feedback mechanisms, receptors, hormones and messenger molecules, many of which are yet to be discovered.

For instance, when there is excess cholesterol available, the liver and other cells cut down cholesterol production. Our liver has the ability not only to produce, but also to get rid of large amounts of cholesterol through bile. The liver cells first display additional LDL receptors on their cell membrane, attracting more of the circulating LDL - which get promptly swallowed by the liver cell. As a result of this soaking up of LDL by the liver, blood cholesterol levels drop.

This excess cholesterol trapped by the liver gets excreted though bile either directly or after conversion to bile acids. Though most of the bile acids eventually get recycled, about 5% of it is lost in stool. This percentage can get manipulated by the body to suit its needs – for instance, during times of plenty, the body might choose to lose a greater amount of cholesterol in bile without reabsorbing it.

In addition to the liver, each cell in our body has fascinating mechanisms to cope with excess cholesterol levels. The cell can decide not to flag down any more circulating LDL, by cutting back on its own LDL receptor production. Once its needs are met, the cell converts all surplus cholesterol into the inactive storage form: cholesterol ester. The cell also tones down the activity of the key enzyme HMG-CoA reductase, which reduces further local production of cholesterol.

Likewise, when there is a lot of cholesterol available in the diet, the body adapts to absorb less cholesterol from the gut after digestion, and vice versa. It is believed that the percentage of cholesterol absorbed from the gut varies between 30-50%. This is the reason why dietary manipulations do not produce big changes in blood levels of cholesterol.

In a dramatic example, the 1991 March issue of the New England Journal of Medicine published a case report of a healthy 88-year-old man who consumed 25 eggs every day, and still had normal cholesterol levels without the help of medication. It was found that his intestine had toned down cholesterol absorption to a radically low 18%, while his liver was able to excrete extraordinary amounts of cholesterol in his bile - thus confirming the extreme adapting ability of the human body in maintaining cholesterol levels.

Almost 25 years later, the USDA has announced that dietary cholesterol is no longer ‘a nutrient of concern’ for people in otherwise good health. While this is not an endorsement to consume unlimited amounts of cholesterol-containing foods, it is indeed such case studies that help us understand the true biology of the human body.

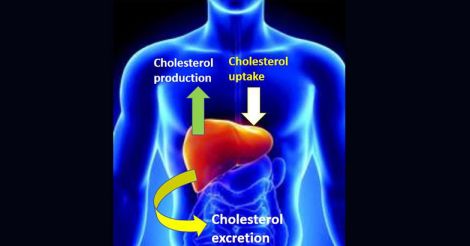

Captain Liver: the liver plays a central role in cholesterol balance. It receives the cholesterol absorbed from food, has the ability to manufacture fresh cholesterol and export it to tissues, import surplus cholesterol picked up from tissues, and excrete any excess in bile. It can self-regulate each of these tasks depending on the body’s changing needs.

Captain Liver: the liver plays a central role in cholesterol balance. It receives the cholesterol absorbed from food, has the ability to manufacture fresh cholesterol and export it to tissues, import surplus cholesterol picked up from tissues, and excrete any excess in bile. It can self-regulate each of these tasks depending on the body’s changing needs.What makes cholesterol levels go up?

When a person is sedentary, energy requirement is small. When such a person consumes excess carbs or sweets, a lot of the absorbed glucose and fructose ends up not being used for energy, and gets converted to cholesterol and fat.

A high fat diet can raise blood cholesterol level. Although vegetable oils do not specifically contain cholesterol, they are made up of triglycerides, which yield fatty acids when broken down. Fatty acids generate acetyl CoA which is the substrate for cholesterol production. Animal products such as meat, dairy and eggs contain cholesterol, though absorption rates can vary.

Medical conditions like diabetes, obesity and hypothyroidism can lead to elevated cholesterol levels. Some people have a genetic tendency for higher cholesterol levels. This is due to a defect in the LDL receptor: which means that the circulating cholesterol in blood cannot be easily removed by the liver or other tissues.

There is controversy regarding normal LDL-C levels, and one level does not fit all. Total cholesterol below 200 mg/dl, LDL-C below 130 mg/dl and HDL-C above 40 mg/dl are desirable for healthy people. For those who have established coronary risk factors such as diabetes, cardiologists recommend a lower range of normal LDL-C. For those who had a heart attack, the target is lowered even further.

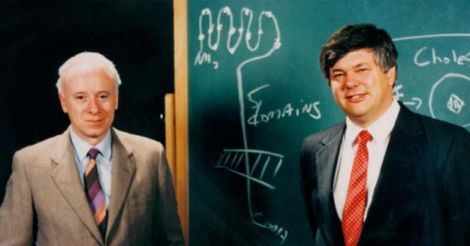

Turning point: the discovery of the LDL receptor earned Joseph L. Goldstein and Michael S. Brown the Nobel prize in 1985 and enhanced our understanding of how the body handles cholesterol.

Turning point: the discovery of the LDL receptor earned Joseph L. Goldstein and Michael S. Brown the Nobel prize in 1985 and enhanced our understanding of how the body handles cholesterol.What can we do to reduce the risk of heart disease?

Though cholesterol is the most talked about, attention must also be paid to all of the other known risk factors associated with heart disease. Age and heredity are important risk factors, but they cannot be altered. What can be altered are lifestyle variables as outlined below:

Regular exercise, a half hour per day at least five days a week is a great investment for the future. Apart from its other health benefits, exercise naturally raises HDL cholesterol, which is considered a good thing.

Limiting the intake of trans-fats (vanaspathy, shortening, cookies, bakery products) reduces the risk of heart disease.

A balanced healthy diet rich in whole-grains, fresh fruits, non-starchy vegetables, fish and lean meat in sensible portions. Intake of sweets and processed foods must be minimised. The details of the perfect diet were outlined in my earlier article.

The use of cooking oils was explained in my earlier article. Regardless of the type of oil used, the safest strategy is ‘the less oil, the better’.

Checking blood pressure and fasting blood sugar once a year will help detect diseases like diabetes and hypertension early enough. Those who are diabetic or hypertensive must strive to maintain their numbers at optimal levels.

Smoking and excessive alcohol consumption are strong modifiable risk factors for heart disease. The complex relationship between alcohol and heart disease was outlined in my earlier article.

Those who are obese should try to bring down their weight, which reduces insulin resistance in the body. Insulin resistance is a key factor that drives inflammation.

Those who have high LDL cholesterol must first try earnestly to reduce the levels by positive lifestyle changes and dietary alteration.

Medications may be required for those who have high LDL-C levels despite lifestyle changes, but only after a detailed assessment of the individual’s coronary risk profile by a doctor.

Getting adequate sleep is important. Lack of sleep increases insulin resistance and adversely affects metabolism.

Reducing stress in life to the extent possible is helpful. While there is no justification for laziness, sometimes, striving for a little less might ensure a longer life.

Glossary

LDL: Low density lipoprotein particle

LDL-C: The cholesterol that is carried by the LDL particle

VLDL: Very low density lipoprotein particle

VLDL-C: The cholesterol that is carried by the VLDL particle

HDL: High density lipoprotein particle

HDL-C: The cholesterol that is carried by the HDL particle

Triglyceride: The basic unit of fat, it has three fatty acids attached to a glycerol stem. Fatty acids are made of carbon chains of assorted lengths.

LDL receptor: A special flag produced by the cell, which can attract and attach LDL particles passing by

LCAT: Lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase, an enzyme that converts free cholesterol to cholesterol ester

Tissue: A collection of cells that work for a common purpose

Further reading

Absorption of cholesterol and other lipids

Drug that raised HDL level unexpectedly increased cardiac deaths: trial halted.

Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology 13th edition

Harper’s Illustrated Biochemistry 30th edition

Hurst’s the Heart manual of cardiology

The ATP-III guidelines on management of high cholesterol levels

(The author is a senior consultant gastroenterologist and deputy medical director, Sunrise group of hospitals)