Human beings are fundamentally pleasure-seeking creatures. This inborn tendency makes us crave for things like fine food, toys, entertainment and the company of those we love. Pleasure can also be derived in several other ways, some of which are quite objectionable. For instance, lust, theft and drug abuse have been classified by contemporary society as wrongful means to attain pleasure.

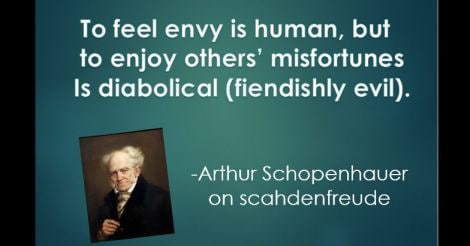

Psychologists have described one such objectionable form of pleasure; it is called schadenfreude (pronounced shaaden-froyda). A term that many have perhaps not heard of, it is a combination of two German words schaden which means damage and freude, which means joy.

Now considered a universal human trait, schadenfreude is defined as the secret feeling of joy or pleasure when we learn about another person’s misfortune.

The most prominent recent example is the mob response that occurred in Kerala following the arrest of a well-known film actor. Large numbers of people abandoned their daily routines and gathered at places where the actor was taken to by police as part of investigation. The crowds waited for long hours with little to do except speculate and exchange conspiracy theories. While it is easy to blame it on moral policing and curiosity related to celebrity status, the real explanation for this phenomenon is schadenfreude. They did it because they derived a sense of pleasure from it.

People love to see others fall into trouble. The more socially prominent that person is, the greater the pleasure.

In everyday life, we get to see different versions of Schadenfreude.

Upon hearing about a couple going through divorce, at least some people feel a secret pleasure deep within themselves, especially if the couple were well-placed in society. When a flourishing business collapses, many people enjoy schadenfreude. If a staff member gets expelled for a wrongful act, it is common for some colleagues to feel a sense of superiority and pleasure. After a top student fails unexpectedly in a class test, more classmates experience schadenfreude than sympathy.

In America, when President Bill Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky became known in 1998, there was an outpouring of Schadenfreude - which was reminiscent of the timeless phrase: “let him without sin cast the first stone”.

People enjoy reading about negative life events of famous and successful people. This is a common example of schadenfreude, the malicious joy derived from others’ suffering. The enormous popularity of celebrity gossip magazines worldwide is built on schadenfreude.

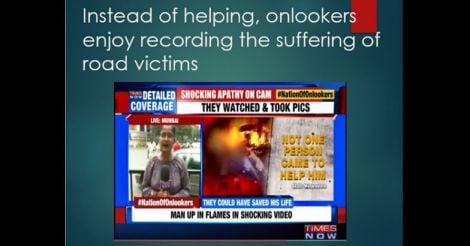

People enjoy reading about negative life events of famous and successful people. This is a common example of schadenfreude, the malicious joy derived from others’ suffering. The enormous popularity of celebrity gossip magazines worldwide is built on schadenfreude.Except for a select few who genuinely want to help the person, many of those who gather around the scene of a road accident are simply curious to know the extent of injury suffered by the victim. They derive a sense of perverted pleasure by reassuring themselves that they are in a better position when compared to the victim. To make it worse, some onlookers record videos of the morbid scene using their mobile phones and circulate it by social media for others to view and enjoy. Such acts serve as shameful contemporary examples of schadenfreude.

Curious onlookers often relish the suffering of road accident victims, at times even hampering rescue efforts. A horrific example of schadenfreude, where man derives sinful pleasure at the expense of another’s suffering.

Curious onlookers often relish the suffering of road accident victims, at times even hampering rescue efforts. A horrific example of schadenfreude, where man derives sinful pleasure at the expense of another’s suffering.Psychologists have long been aware of this phenomenon. Professor Susan T. Fiske from Princeton university performed studies on volunteers with the help of electromyograms—by placing electrodes that measured the activity of cheek muscles used for smiling, an objective measure of pleasure. The volunteers were then shown various hypothetical scenarios of people doing well and otherwise. The results showed that the volunteers experienced greater enjoyment while witnessing bad outcomes happening to high achievers. Cleverly designed studies using functional MRI scans have confirmed these observations.

Interestingly, schadenfreude is one of the cornerstones of humour. Consider, for example, the so-called ‘funny videos’ that are shown on TV or going viral on YouTube. Most of them involve a downfall: a mistake or injury happening to another person. The familiar cartoon of an obese person slipping on a banana peel and falling is considered funny for the same reason. Most people get a sense of pleasure and elevation of status by reassuring themselves that compared to the person in the video, their own position is safe and secure; the laughter being instinctive.

On the other hand, few people would acknowledge the pain or injury suffered by the other person.

What is the reason for schadenfreude?

Human beings are a competitive species; we frequently do a self-assessment by comparing ourselves to others. Social comparisons are a way of life. According to Professor Richard H. Smith, in evolutionary psychology, as man pursues high status, one way he affirms that is through a reduction in status of other people, especially those of higher status. When a misfortune happens to another person in our society, we get a false sense of promotion of our status. Relativity plays a role here.

Relativity is explained as follows. Imagine that we are seated by the window inside a stationary train, while another train is parked on the parallel track just outside our window. If the other train slowly moves backward, for a moment, most of us will get a sense that our train has started moving forward.

Similarly, as we witness the fall of another person, we get a false sense of elevation, and this is the basis of Schadenfreude.

In his book ‘The Joy of Pain’ psychologist Professor Richard H. Smith writes:

“Comparisons with others and the conclusions we make about ourselves based on them, and the resulting emotions pervade most of our lives. As much as inferiority makes us feel bad, superiority makes us feel good. The simple truth is that misfortunes happening to others are one path to the joys of superiority and help explain many instances of schadenfreude.”

Is it normal?

Much debate has occurred over whether schadenfreude is a normal human emotion. Many psychologists believe that it is normal, but perhaps the most evil of all human emotion. There is no disagreement that schadenfreude must be suppressed to the extent possible. However, for that to happen, we need to be acutely aware of its existence.

What kind of people engage in schadenfreude?

Schadenfreude is exhibited predominantly by people of low self-esteem. Low self-esteem can be habitual for certain people who continue to feel worthless despite all the success they achieved in life. It can also be the aftermath of continued failures in life, or poor adaptation to failure. Desperate for that elusive bright spark of personal success, these people fool themselves into believing that they have succeeded, while passively witnessing the failure of others. Such people are frequently seen browsing gossip magazines for negative news about famous and successful people.

How is Schadenfreude different from envy?

It is easy to confuse schadenfreude with envy. While schadenfreude refers to happiness at another person’s misfortune, envy is its counterpart, defined as unhappiness at the other person’s good fortune. For example, when a colleague acquires a brand-new luxury car, most people would feel envy—although a few would overcome it and even deliver a genuine compliment.

In this case, envy stems from the longing for the other person’s possession or status. This is the ‘I wish I could have what you have’ type of benign envy. Envy can also be malicious: the ‘I wish you didn’t have what you have’ type.

Though an undesirable attribute, benign envy can sometimes be used constructively to better one’s own performance through hard work: for instance, in sports, studies, art or business.

Schadenfreude, on the other hand is a pleasurable emotion that necessarily requires another person’s downfall. In the example above, if the colleague crashes his new luxury car, many people would feel schadenfreude. Unlike envy which makes one feel uncomfortable and negative, schadenfreude makes the person feel good.

Envy and schadenfreude, though different emotions, go hand-in-hand. Schadenfreude peaks when misfortune happens to those whom we envy the most.

What is the right approach then, if misfortune befalls someone?

To start with, one must be careful to avoid feeling the secret pleasure when news breaks about another person’s misfortune. The tendency to play judge by making statements about the person’s ‘previous actions’ bringing on a ‘deserved outcome’ should also be curbed.

In an ideal world, the correct response to such a situation is empathy. Empathy is the ability to put oneself in another person’s shoes and see the world from that person’s perspective. Only the most intelligent and socially evolved people have the quality of empathy, although it is something that can, and should be taught early at home and in school. An empathetic person offers help to the fallen person if within the sphere of influence. If it is not practical to offer help, the person moves on without dwelling too much on the details or spreading rumors.

In summary, schadenfreude is the sinful pleasure we might feel when misfortune happens to other people-particularly those who are successful and popular. Although this is basic human nature stemming from social comparison, it must be actively discouraged. Awareness about this entity is crucial in order to overcome it. Empathy is the civil alternative to schadenfreude.

Further Reading

1. Paper by Prof. Susan T. Fiske on the wide-reaching effects of social comparison

2. The Joy of Pain: Book written by Prof. Richard Smith on the topic of schadenfreude

3. Sorrow so sweet: a guilty pleasure in another’s woe

(The author is a senior consultant gastroenterologist and deputy medical director, Sunrise group of hospitals)

Read more: Latest from Wellness | Health | Shield eyes from infection during monsoon