As it preps to go for the most decisive polls of the year, also deemed as the semi-final showdown before the 2019 general elections, Karnataka’s electoral fate hangs in suspense.

Though all the opinion surveys and poll pundits have predicted a hung assembly, they might as well expect to be confounded for the state has the unique distinction of having the most interesting “caste-class-power” configuration among all its southern counterparts.

Here are a few interesting facts that tell us why Battleground Karnataka will be crucial - In the last three decades, the people of the state have never voted a ruling government back to power. In comparison to its southern neighbours, Karnataka also holds the dubious record of casting votes in an uneven manner, making polling patterns difficult to predict. Of the 19 chief ministers the state has had since independence, none came from the oppressed Dalit minority. Strangely, Karnataka is believed to mostly elect a party that is different from the incumbent central government.

So, will the present assembly elections change a few of these jinxed traditions? Or will the voters fall prey to caste appeasements and fragmented vote-bank politics? We are sure to find out soon. However, here’s a brief outline of recent developments furthering the legacy of caste-based politics in Karnataka.

The class-caste-power nexus

Despite any reliable sources of data that validate the strength and distribution of various castes in Karnataka, it is still believed that two communities have mostly controlled the power dichotomy in the state. In his 1994 book titled, 'The Politics of India since Independence', Paul Brass explains that in Karnataka, Lingayats and Vokkaligas were considered very powerful since the early independence-era.

In fact, most of Karnataka’s chief ministers since 1950s (14 out of 19) have come from either one of these dominant castes. Brass also examines one of the earliest examples of caste-based appeasements in Karnataka politics by citing the election campaign of the Congress party in 1978. In order to expand his vote bank, Devraj Urs, the then Congress leader decided to field a large number of people from minority communities to contest the polls. However, the move was resented by a few party members who opposed the preponderance of various castes.

Prime minister Narendra Modi has been on a hectic campaign in the state in the final stages of electioneering.

Prime minister Narendra Modi has been on a hectic campaign in the state in the final stages of electioneering. Cut to 2018, the three leading parties in Karnataka seem keen to please particular sections of people to strengthen their vote banks. Even as present CM Siddaramaiah and his Congress party are busy promoting their AHINDA (people belonging to SC/STs and OBCs) slant, tainted leader B S Yeddyurappa’s BJP is leaving no stone unturned in polarising votes along the Hindutva lines. Considered the dark horse in the race, Kumarswamy’s JDS is consolidating its Vokkaliga vote base in the hope of playing the role of kingmakers, in case of a much-expected hung assembly scenario.

Of tall claims and caste based appeasements

To better understand voting patterns, the state can largely be divided into six regions- Hyderabad Karnataka, Bombay Karnataka, Central Karnataka, Bengaluru, Old Mysore and coastal Karnataka. The interesting aspect, however, is how political strategies and election gimmicks are tailor-made to suit and influence voters in each of these electoral geographies. While coastal Karnataka stands out as a tried-and-tested field for Hindutva-related experimentations, Hyderabad and Bombay Karnataka are where the Lingayat agitation has gained momentum.

In adherence to his AHINDA propaganda, Congress leader Siddaramaiah has already assured that he would increase the reservation scale in the state to a significant 70% if his government is voted back to power. Speaking of more promises made: BJP’s proposed CM candidate B S Yeddyurappa has taken a pro-framer approach by assuring farm loan waivers if they win; and JDS unlike other parties has taken the high road by promising measures that empower women. Case in point, the 50% rebate on land registered under the name of women and monthly living assistance to women from poorer sections etc…

Congress chief Rahul Gandhi during an election rally.

Congress chief Rahul Gandhi during an election rally.In the middle of these tall claims and caste- and class-based appeasements, CM Siddaramaiah’s much-calculated move to accord separate religious minority status to Lingayats in the state (under section 2d of the Karnataka Minorities Act) has been deemed the elephant in the room. Mostly because of the nuanced nature of the issue, that has left even Lingayats questioning the very nature of their religious identity.

The Lingayat debate - a religious crusade or a poll propaganda?

To put things in context for the uninitiated, the demand to issue a separate religious identity for Lingayats is not new and dates back to several years. However, it was only a few years ago that proponents of this faith (who mainly follow Basava Thattva - teachings of the 12th century social reformer Basava, who rebelled against caste hierarchy, gender discrimination and denounced Vedic practices) galvanised support from within the community to be accorded a religious minority status that separates them from Hindus (who follow Vedic rituals and acknowledge caste distinctions).

And where does the nuance come in? “The Lingayat movement also calls out that they be distinguished from Veerashaivas (worshippers of Lord Shiva and the followers of pancha peethas and vedic texts). “For centuries now, the terms Lingayat and Veerashaiva have been used interchangeably. Several Mathas in Karnataka like the Suttur and Sidaganga matha teach Vedic texts till date. Even the Hindu Religious Act recognizes Lingayats and Veerashaivas as Hindus. Hence, these castes are both religious denominations of Hinduism,” reasons out M Chidananda Murthy, a retired Kannada professor and religious researcher.

Rahul Gandhi with a senior Lingayat seer.

Rahul Gandhi with a senior Lingayat seer.He is unsure if the Centre is likely to budge and accord religious minority status to Lingayats under the Central Minority Commission Act. When asked if this timely move by Congress is likely to swing Lingayat votes in favour of Congress, the 88-year-old refrains from giving any answer.

However, according to 56-year-old S M Jamdar, the crucial decision by Siddaramaiah led Congress government will “considerably” influence Lingayat votes. “Our movement was never about being accorded a religious minority status. We wanted to stand independent of other religions that do not follow Basava thattva (including Veerashaivas). But there is no provision in the Constitution to suit this and hence we were left only with the religious minority option wherein a religious community other than proving that they differ from other religions needs to also validate that they are a numerical minority. So it is killing two birds with a single stone,” explains Jamdar, who led the Lingayat agitation from the front.

Who will win the throne?

If approved by the central government, the separate religious minority status to Lingayats entitles them to more educational and employment-related reservations, scholarships and subsidies for the poor and even a separate code.

So, has this crucial move by the Congress affected BJP’s aspirations in Karnataka by splitting its votes? “Yes, it has certainly left the house divided. Though I cannot surely say that it will benefit the Congress party, it has definitely split the BJP vote and has also completely diminished or shrunk the position of B S Yeddyurappa as its unquestioned Lingayat leader of Karnataka,” opines Vasanathi Hariprakash, senior journalist who has just finished touring nine districts of Karnataka, to check the pulse of the state before it goes to vote.

Finally, will the BJP benefit from anti-incumbency? Will the Congress be re-elected with a full majority? Or will JDS script new history? More interestingly, who will side with whom in case of a hung assembly? With just hours to go for the polls, its curtains down on mutt hopping by senior party leaders, political slandering, personal campaign attacks and desperate attempts to polarize voters in every way possible.

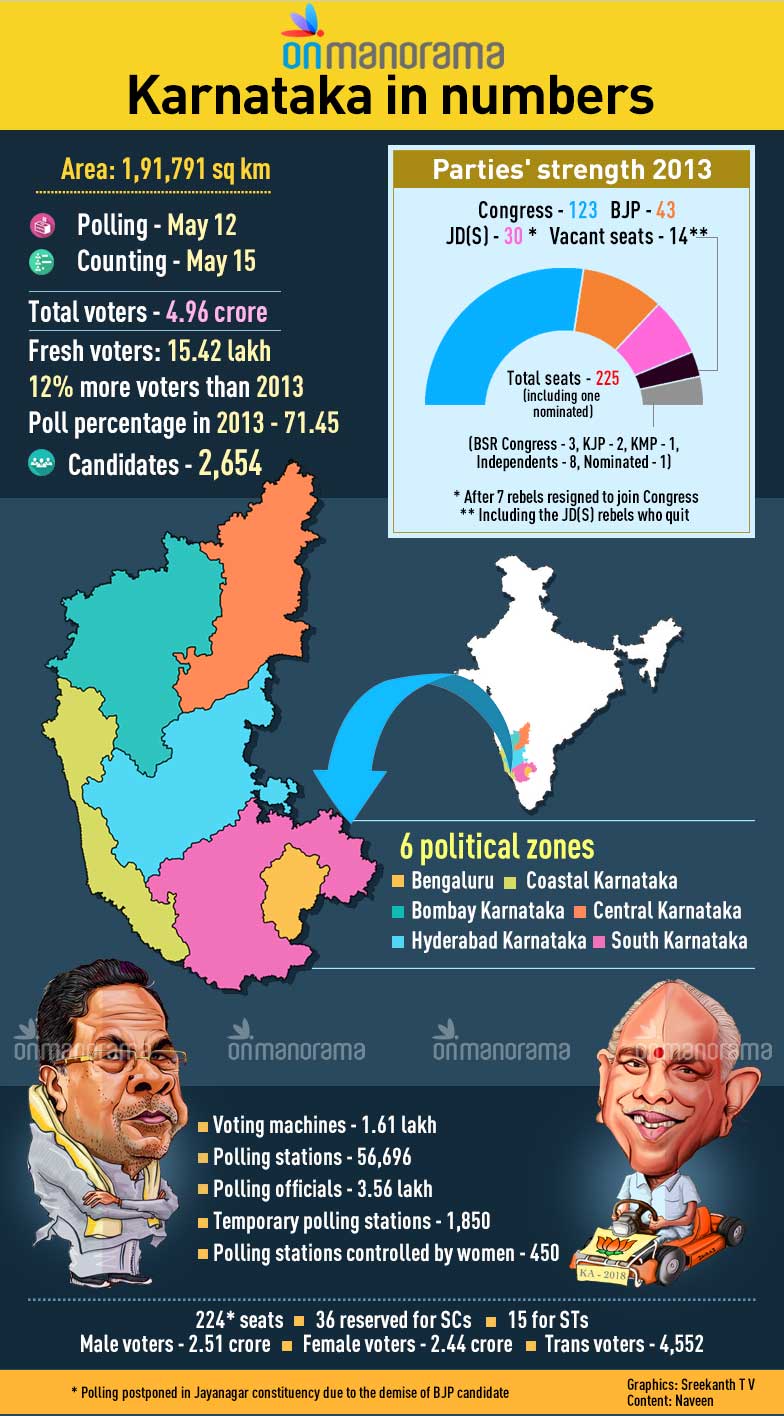

The answer to all the big questions now rest with the 4.96 crore voters of Karnataka.

CM Siddaramaiah (Centre) and his Congress party are busy propagating their AHINDA programme, tainted leader B S Yeddyurappa’s (Left) BJP is leaving no stone unturned in polarizing votes along the Hindutva lines. Considered the dark horse in the race, Kumarswamy’s (Right) JDS is consolidating its Vokkaliga vote base.

CM Siddaramaiah (Centre) and his Congress party are busy propagating their AHINDA programme, tainted leader B S Yeddyurappa’s (Left) BJP is leaving no stone unturned in polarizing votes along the Hindutva lines. Considered the dark horse in the race, Kumarswamy’s (Right) JDS is consolidating its Vokkaliga vote base.