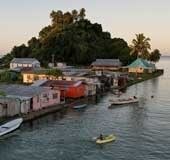

The civil war in Sri Lanka between the Sri Lanka Government and the Tamil Tigers ended on May 16, 2009, when the Sri Lankan government declared victory. The following day, an official Tiger website conceded that "This battle has reached its bitter end." People in Sri Lanka and around the world heaved a sigh of relief that the devastating conflict had finally ended after 26 years of hideous atrocities on both sides, and some 100,000 deaths. Since then, Sri Lanka has been trying to heal the wounds of war through a process of reconciliation with the Tamils and fixing accountability on the perpetrators of war crimes. Both these issues have been engaging the attention of the Sri Lankan Government and the international community.

The Tamil factor

It is public knowledge and well documented that there have been excesses committed by the Sinhala soldiers against the Tamil Tigers. The hatred was mutual and the atrocities committed by the Tigers were no less than those of the army. India’s problems began once the war ended because it became India’s responsibility to prevent the total annihilation of Tamils in Sri Lanka and to rehabilitate the survivors. Sri Lanka virtually abandoned the 13th amendment and even diverted resources made available by the international community as humanitarian assistance to the displaced persons.

The western resolutions approved by the Human Rights Council from year to year were acceptable to us and India voted for the resolution once when Sri Lanka openly defied India’s advice. The western countries kept diluting the resolution to secure the Indian vote, but the Indian dilemma was acute because of the solid support Sri Lanka received from China and Pakistan.

The HRC resolution this year, as in previous years, centred around the demand for an international probe into alleged war crimes by the Sri Lankan army during the civil war and India could not have voted against it, given the sentiments in Tamil Nadu on the eve of a decisive election there. At the same time, India could not have supported the resolution. Consequently, India resorted to an abstention, which was applauded by Sri Lanka.

The fate of the resolution

Twenty-two countries voted in favour of the text, 11 opposed and 14 abstained. The resolution expressed "deep concern" at the “deteriorating situation" in Sri Lanka, and criticised the erosion of judicial independence, marginalisation of minorities and impunity. The text pointed to trends emerging over the past year, which represent clear early “warning signs of a deteriorating human rights situation in Sri Lanka.”

Though the resolution was adopted, the negative votes (11) and abstentions (14) put together showed that a majority of the Council did not support the move. India’s explanation of its vote pleased Sri Lanka as India stated that an intrusive approach would undermine Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and institutions. Sri Lanka argued that the HRC resolution was not supported by many countries, including China, Japan, India, Israel and Russia. India has an established position that it would not support country-specific resolutions unless they are unanimous, considering that human rights resolutions are being used to target developing countries. Sri Lanka has rejected any possibility of an international investigation, claiming that the Government has immense domestic support as evidenced in recent elections.

In any event, Sri Lanka has time to reach an understanding with the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights before any international investigation is launched. Like in the case of China, which turned an investigation into the origin of COVID-19 into a farce with the connivance of the WHO, a similar arrangement may be worked out with the UN High Commissioner of Human Rights.

What has helped Sri Lanka in its battles in the HRC is the Sino-Indian rivalry in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka has banked on China for its economic development even as it declares spiritual and historical linkages with India. China has no interest in the Tamils, while India has the obligation to look after the interests of the minorities. Moreover, as a permanent member of the Security Council, China can prevent any punitive action against Sri Lanka even if it flouts the HRC resolution.

Sri Lanka's tactics

The comparatively noiseless virtual meet of the HRC also seems to have helped Sri Lanka. The usual sights of NGOs chasing delegates to lobby for their causes may have been absent this time. Since many of the actions of the HRC are prompted by human rights activists, their absence must have permitted Sri Lanka to lobby with Governments and play for time. The tactic adopted by Sri Lanka was to project the resolution as an attempt by western countries to bully small countries. The positions of India and China gave courage to Sri Lanka to reject the resolution. But if Sri Lanka simultaneously takes some action to address the concerns of the Tamils with Indian cooperation, the pressure of the HRC will wither away and India may be able to prevent Sri Lanka from opting for a tight embrace with China.

The activism of the HRC is generally swayed by political considerations and not by humanitarian compulsions. If Sri Lanka manages to strengthen the reconciliation process in a visible manner and improves the deteriorating humanitarian situation in the last two years, it can gradually avoid a severe international investigation into violation of human rights. Sri Lanka has been given four years to solve the issues, failing which the country will be brought before the Human Rights Council once again.