Wayanad: Ageing tigers, deteriorating quality of forests, dwindling prey population and overcrowded palliative care facility are giving a tough time for the forest department in the Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary (WWS) and adjacent zones.

According to the latest Tiger Census Report (2022) of the forest department, there are 84 tigers in the WWS, a significant drop from 2018 when 120 tigers roamed the region. In the past three years, more than 10 tigers were found dead, and many had ghastly wounds from fighting other big cats.

According to wildlife experts, there was a boom in tiger population between 2010 and 2015. But most of those tigers are aged now and are fighting for survival.

Survival of the 'youngest'

As per the Status of Tigers in India report of 2022 by the National Tiger Conservation Authority, there are 5.3 tigers per 100 square kilometres in Wayanad, which has the highest density of big cats in Kerala. But in WWS, the aged tigers are getting pushed to the fringes of the forests, by the young and energetic ones.

“It is truly a tough time,” said Dr Arun Zachariah, renowned wildlife veterinarian. “We are facing a challenge as the number of aged animals, and those seriously injured and incapacitated by infighting have been increasing.”

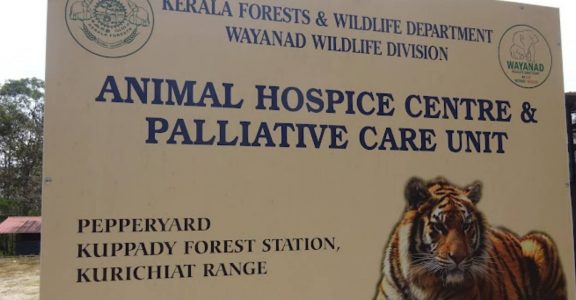

Dr Zachariah said the aged tigers, often left without hunting teeth or damaged claws, turn to 'soft prey' like domesticated cattle that are tied up. And that puts the forest department in a Catch-22 situation. On the one hand, they are under pressure from the agrarian population that demands the capture of the hapless tiger; on the other, they cannot hold the animal in captivity for long because the Animal Hospice and Palliative Care unit in the sanctuary is overcrowded.

Smaller hospice for ‘Big Cats’

Started a year ago, the Rs 1.12-crore hospice was envisaged to accommodate only four animals, but now it is packed with six. An old tigress that killed several cattle before being caught from Moolamkavu under the Sulthan Bathery Forest Range is one of the inmates.

When caught in a trap set by the forest department, the animal had deep wounds on the neck, no hunting teeth and a fractured front leg. Knowing it wouldn't survive in the jungle, the forest department accommodated it in the hospice.

The tigers that are seriously injured, but young, would be released into the jungle once they regain health. However, the aged and permanently incapacitated ones will be kept at the hospice or rehabilitated in zoos elsewhere.

Though demand for capturing the problem animals from various quarters has been on the rise, forest officials are hesitant as there is no space to keep them safely.

Moreover, even those that are released in the wild after treatment return to the same habitat, posing threats to the agrarian community. Once a tiger is captured, the villagers spend sleepless nights to ensure that the forest officials don't release it in the same forest. However, the forest officials say that even if the animal was released in a different spot, in most of the cases the animal returns to the earlier areas.

An aged tiger that was captured from Panavally in the Tirunelli panchayat earlier this year, was released in the deep forest. But it is still on the prowl across human habitats, forest department officials said.

An official of the WWS told Onmanorama that a proposal for an additional, improved unit of the animal hospice is still pending in the headquarters. Envisaged on a 1 sq. km area, the facility will be behind a 5-metre-high wall, secured with an iron net and individual space for each tiger.

Depleting quality of jungle and prey

The depleting quality of forests with the spread of invasive alien species across forest ranges and a dip in the number of prey animals have also aggravated the situation.

N Badusha, president, of Wayanad Prakrithi Samrakshana Samithy, said the sanctuary is gradually becoming uninhabitable for big animals. “The invasion of alien tree species has hit at large the quality of fodder for prey animals, as the grasslands and bamboo forests are fast vanishing due to the invasive trees,” said Badusha,

Though the forest department had launched a Rs 5.31-crore project to eradicate invasive species like Senna Spectabilis ('manjakkonna' in Malayalam) from 1,672 hectares under the Muthanga and Kurichiad forest ranges of WWS, the project is yet to prove a success.

“There is no grass and other vegetation endear to the herbivorous prey population as the entire stretches of these ranges have been monopolised by the alien species,” said Badusha, adding that the prey animal population is reluctant to reside amid these species.

Wildlife experts point out that the spotted deer and wild boar populations inside the jungle are also depleting fast, abetting the fighting between big cats for prey and resulting in continuous raids on human habitation.