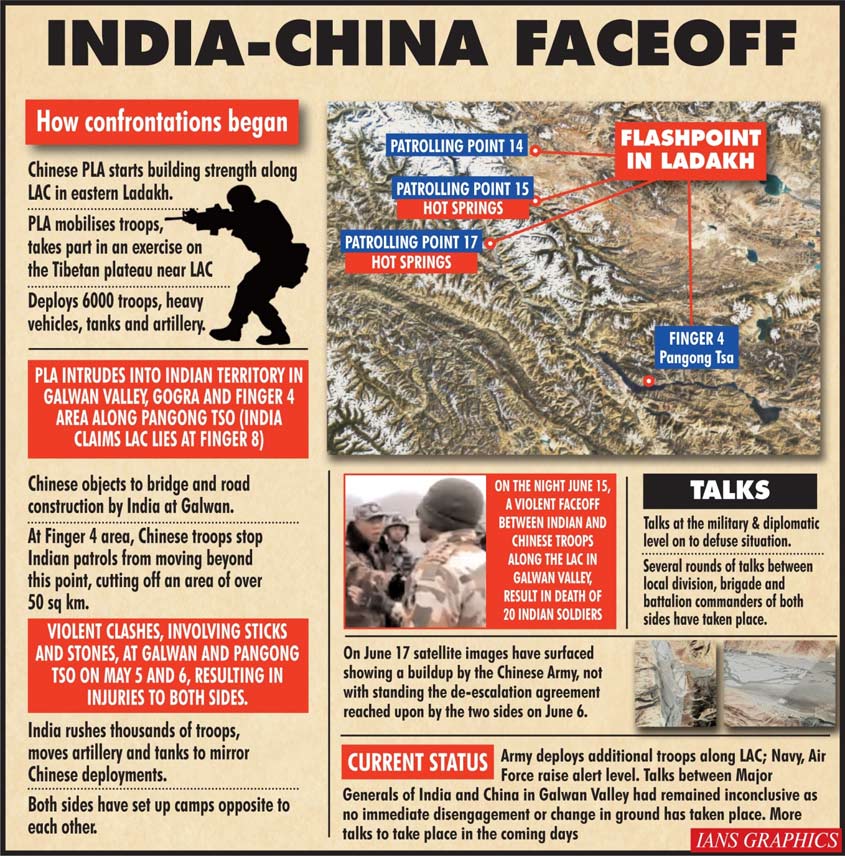

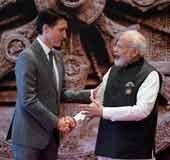

The cold-blooded massacre of 20 Indian soldiers, including a young Colonel by China, and its continuing belligerence have taken the conflict with the Chinese to a new level of escalation. No shots were fired, but the martyrs endured more pain on account of the crude weapons used. More than a dozen meetings between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jin Ping, including informal summits in Wuhan and Mamallapuram and five Prime Ministerial visits to China, had given the impression to the world that the two Asian giants were on their way to build an equation for peace and development in the region. Those hopes have been shattered by the confrontation with the Indian soldiers along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) at Daulat Beg Oldi, Galwan Valley, the Pangong Lake, Bararahoti, and Naku La in Sikkim.

“To teach India a lesson” was considered by China an adequate explanation for a war in 1962. The same justification was given for the Doklam stand-off in 2017 and it will not be too long before China gives the same explanation for the recent developments.

Golden period

The years from 1947 to 1962 were the golden years of Indian foreign policy. India became a natural leader of the Third World as a country that won its Independence without firing a shot and a champion of decolonisation, disarmament, equitable economic development and Afro-Asian solidarity, formalised in the Belgrade conference. There was even talk of India taking over the permanent seat of China in the UN Security Council. At that point, China decided to teach us a lesson that there was another powerful country in Asia to rival India by use of force, if necessary.

Doklam crisis came at a time when India had managed to work out a relationship with the Trump Administration in spite of the unpredictability of US policies and President Trump’s withdrawal from the international scene. India and the US had begun to work together bilaterally and internationally, even though there were issues relating to Russia and Iran. Doklam may well have been the cumulative effect of India’s growth and popularity. Unlike the previous intrusions along the LAC, the event was staged at the India-Bhutan-China tri-junction, the status of which was supposed to be respected by both India and China. A part of the reason for choosing this venue may have been to wean India’s best friend, Bhutan, away from us by questioning our locus standi in the situation. A confrontation was avoided after a series of threats and there are still reports of a threatening presence of China in the area.

Surprise is a Chinese characteristic in most of its actions, but the latest border skirmish was a real bolt from the blue because it came in the midst of COVID-19, when nations should be working together to avert an existential threat to mankind. In fact, there is a call from the Secretary General of the UN that there should be a general ceasefire, regardless of the position of the combatants. But on May 5, a scuffle broke out between the Indian and Chinese troops at the Pangong Tso lake, located 14,000 feet above the sea level in Ladakh. Soldiers from both nations engaged in fistfights and stone-pelting at the LAC. The incident, which continued until the next day, resulted in several soldiers being injured on both sides.

Three days later and nearly 1,200km (745 miles) away to the east along the LAC, another fight erupted at Naku La in Sikkim after the Indian soldiers stopped a patrol party from the Chinese Army. Both countries downplayed the incidents and the issues were resolved at the local commander level, as has generally been done in the past. But the Chinese went incommunicado while reports came of troop movements and threat of escalation.

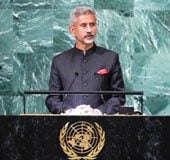

"China is committed to safeguarding the security of its national territorial sovereignty, as well as safeguarding peace and stability in the China-India border areas," the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson said in a statement. The Ministry of External Affairs stated that it was in talks with China to deal with the standoff. But President Trump saw the situation as a “raging border dispute" and offered to mediate. When he was in India a few weeks earlier for Namaste Trump, he was not even aware that India and China had common borders.

The offer of mediation by President Trump had an electrifying effect on India and China and both sides quickly began talking of peace. The Chinese envoy underlined how the two nations are fighting the scourge of COVID-19 together and urged both to view each other favourably. "We are engaged with the Chinese side to peacefully resolve this issue," foreign ministry spokesman said. "Our troops have taken a responsible approach towards border management and are following protocols."

But tension remained in the area, because the Chinese troops had come much beyond their claim line this time. At least 10,000 PLA soldiers were believed to be camping on what India claimed to be its territory. Army chief General Manoj Mukund Naravane’s visit to Leh and many high level consultations in Delhi conveyed the impression that the Chinese action this time went beyond theatricals and show of force and that there were bigger things involved.

Provocation for China

The COVID-19 pandemic is bound to change the international pecking order and China is very much a candidate for world leadership, though its role in the pandemic drama, prima facie, is that of the villain. The US is in doldrums and unless the election changes its prospects, the US cannot lead the new global order. Russian President Vladimir Putin and the European Union are still struggling to save lives and livelihoods. This situation gave a window of opportunity to India since it played its cards well by focussing on the war against COVID without engaging in polemics. It has also become “the healer of the world”, sharing knowledge, medicines and equipment and emphasising multilateralism in solving global issues. This is by itself a provocation for China and it wants to serve notice that India should not entertain any hope of global leadership. At the World Health Assembly, India co-sponsored a resolution urging a review of COVID developments, but said nothing that would alter the status of Taiwan. We have done well, but China would like India to be more “friendly.” In other words, the agenda this time was larger than before.

It had appeared initially that the massacre of June 15 shocked both sides to disengage on all fronts, including Galwan. But subsequent developments like the Chinese build-up in the area indicated that the episode had not ended. But it is quite possible that there may be a lull again on the border and the border talks might be resumed. India’s options are limited, but a restatement of our position and a clear determination of the Chinese intention will be essential. Clearly, it was our judgment that the matter could be resolved by negotiations that led to the tragedy. We were blinded by the “Wuhan Spirit” and the “Chennai Change.” The time has come to see the reality.

(The author is a former diplomat who writes on India's external relations and the Indian diaspora)