How internet facilitates suicide and their correlation

The information available on social media on suicide can influence suicidal behaviour, both negatively and positively.

The information available on social media on suicide can influence suicidal behaviour, both negatively and positively.

The information available on social media on suicide can influence suicidal behaviour, both negatively and positively.

The suicides of three boys aged around 17, in a span of one month and within a 10-km radius in Wayanad, hit headlines suspecting cyber-triggered suicides. Two of them were known to each other and had followed similar pages on Instagram. However, they deleted the posts before committing suicide, making it difficult for the investigating team to track the other youngsters, who are following the same pages or hashtags. Only the third suicide gave a hint that the boy might have been under the influence of some social media group. When his relatives insisted on a police probe, it was found that a month ago, his friend had committed suicide in a similar way. Shockingly another friend of them had also hanged himself to death a week ago.

In the case of the teenagers from Wayanad, some Instagram accounts and hashtags are the only possible connecting links for the investigation, which is still in a preliminary stage. Their posts were glorifying solitude and death. Now, other friends of these boys who showed similar interests are being tracked to avoid any unfortunate incidents in the future. Although the investigation of these cases is in a very preliminary stage to determine what could be the actual reason for these suicides, it is advisable to make ourselves aware of various suicides among teenagers which are cyber-triggered.

The recent life story from China

Hu Jianguo, father of a 21-year-old man who committed suicide, embarked on a mission to help others after he found that his son was among the community of young people planning to take their own lives together.

In May, after two years of planning and days of conversations in the online group, the 21-year-old rode a train more than 1,000km from his hometown in Guan county, in northern China’s Hebei province, to the central city of Wuhan, where two strangers were waiting for him. Together, as meticulously planned on a private chat group, the three of them took their own lives, leaving a note that offered no answers.

Hu then revealed his identity and tried to take members of the group out of suicide. But they responded with fierce opposition, telling him to leave them alone, that they wanted only to die. There were 475 members in the group when Hu joined, mostly in their teens and twenties. Hu reached out to about 50 of them one by one, trying to find out what their troubles were. Their messages flooded non-stop into Hu’s phone, sometimes until 3 or 4 in the morning.

They mostly discussed ways to die, with their own in-group jargon and glorified code names for suicide methods that served to embolden them and normalise their plans, such as 'swinging', 'diving' or 'barbecue'. In the extreme case, he could call the police and stop the disaster.

“Cyber suicide”

It is the term used in reference to suicide and its ideations on the internet. It is associated with websites or social media platforms which lure vulnerable members of society and empower them with various methods and approaches to deliberate self-harm.

Cyber suicides can be broadly classified into two categories. The first case, which is being discussed, includes those youngsters, getting influenced by the peer pressure. They become a member of some social media group which promotes suicide, discusses ways and means of committing suicide, glorify it, etc. In the process these teens may finally decide to commit suicide which is known as online suicide pact. It is an agreement between two or more people to commit suicide at a particular time and often by the same lethal means, and such a pact is formed or developed in some way through the use of internet and social media.

The first ever documented use of the internet to form a suicide pact was reported in Japan in 2000. However, it has now become a more common form of suicide in Japan, where the suicide rate increased from 34 in 2003 to 91 in 2005.

The second form of suicide is Cyberbullicide, which is more prevalent, the term used to define suicides due to having indirect or direct experiences with online aggression, for instances - online harassment and cyberbullying. Social networking sites regardless of security measure, can only offer a certain amount of protection to the privacy of the user and those are often overlooked by the younger users. By being on websites such as Facebook, Instagram, users make them open and vulnerable to online attacks and harassment from online predators.

The murky cyber world

Social media and suicide are a relatively new phenomenon, which influences suicide-related behaviour. Suicide is a leading cause of death worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, in 2020, approximately 1.53 million people will die from suicide. A fundamental question is whether there is any association between rates of internet and social media use, and suicide rates. Studies show that the prevalence of internet users was positively correlated with general population suicide rates.

An immense quantity of information on the topic of suicide is available on the internet and via social media. The information available on social media on suicide can influence suicidal behaviour, both negatively and positively.

Contributors to social media platforms may also exert peer pressure to commit suicide, idolise those who have committed suicide, and facilitate suicide pacts. For example, on a Japanese message board in 2008 it was shared that a person can kill himself/herself using hydrogen sulphide gas. Shortly after that, 220 people attempted suicide in this way, and 208 were successful.

Availability of suicide or self-harm videos online may normalise and reinforce self-injurious behaviours or cause disinhibition. Social media platforms such as chat rooms and discussion forums may also pose a risk for vulnerable groups by influencing decisions to die by suicide.

Contagion effect

Suicide contagion can be viewed within the larger context of behavioural contagion, which has been described as a situation in which the same behaviour spreads quickly and spontaneously through a group. Persons most susceptible to suicide contagions are those under 25 years of age. A recent study specifically examined possible contagion effects on suicidal behaviour via the internet and social media. Of 719 individuals aged 14 to 24 years, 79 per cent reported being exposed to suicide-related content through family, friends, and traditional news media such as newspapers, and 59 per cent found such content through internet sources.

Studies show that the person who have seen the suicide, either live, through video, or seen the body after the suicide, are more likely to end their lives. One study found that people who knew someone who died by suicide were 1.6 times more likely to have suicidal thoughts, 2.9 times more likely to make a suicide plan, and 3.7 times more likely to make a suicide attempt than people who did not know someone who died by suicide.

Social media as a preventive tool

Social media has also got several platforms to identify and prevent suicide. For example, the Facebook pages of The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and American Foundation of Suicide Prevention had more than 77,200 fans. Both of these Facebook pages provide links to suicide prevention websites and hotlines, as well as information about the warning signs of suicide.

There are 580 groups on Twitter and 385 blog profiles on Blogger.com designated as suicide prevention. These social media sites allow users to interact and share relevant information. Social networking sites Facebook, MySpace, and Bebo have collaborated with the United Kingdom Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre to provide a panic-button application to give users an easy way to report cyberbullying.

Google search engine has made the algorithm in such a way that if any one searches for ways and methods to commit suicide, the results will show the pages of suicide prevention support groups and their contact numbers, for example AASRA.

What parents can do

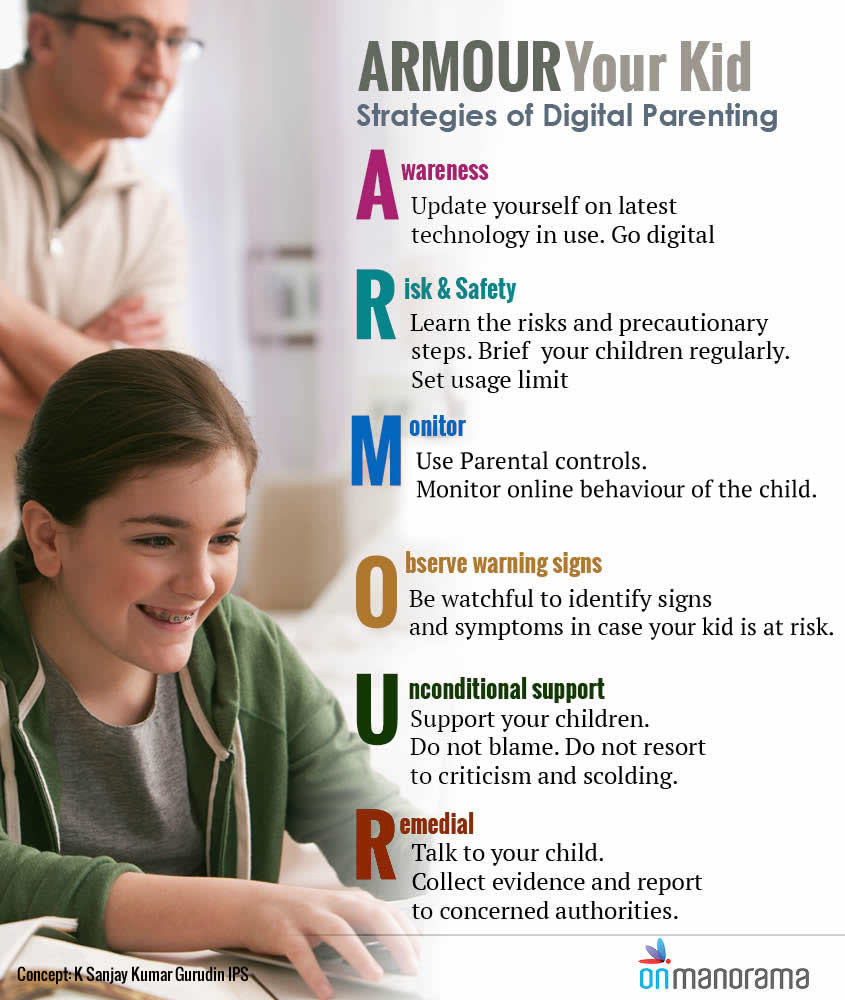

Parents can’t control everything children see online so making them aware about the risks, developing their skills and increasing their resilience in the digital world to face any setbacks and safely navigate through the dangers of the virtual world is the way forward. Another important thing to understand is that parents must keep the lines of positive and healthy communication open. Not just once or twice – but all the time.

Parents should themselves be aware about the risks and dangers associated with internet and social networking sites. They should also know what are the warning signs and symptoms to identify if their kids are facing some difficulty.

By having conversations on a regular basis your kids and teens may feel more compelled to confide in you. If they do, take it very seriously, never overlook. Even if it’s something you may feel is trivial, a kid or teen can be consumed with the incident and take it to a whole a new level.

If you have difficulties getting your kids and teens to talk with you, offer them other alternatives such as another family member, a close family friend, a counsellor, clergy member or a doctor.

(The author, an IPS officer of the 2005 batch, Kerala cadre, is a socially conscious cop, a wellknown cyber expert, and an author of the must-read book 'Is Your Child Safe?' He has had an outstanding and illustrious career as senior superintendent of police in Kerala. Direct your queries to korisanjay7ips@gmail.com)