How a 36-year-old with just 2-3 months to live got a new lease of life

A heart transplant surgery was rare in India, and in Kerala, it was just a dream. All the doctors who worked with me had concerns if the surgery could be performed successfully.

A heart transplant surgery was rare in India, and in Kerala, it was just a dream. All the doctors who worked with me had concerns if the surgery could be performed successfully.

A heart transplant surgery was rare in India, and in Kerala, it was just a dream. All the doctors who worked with me had concerns if the surgery could be performed successfully.

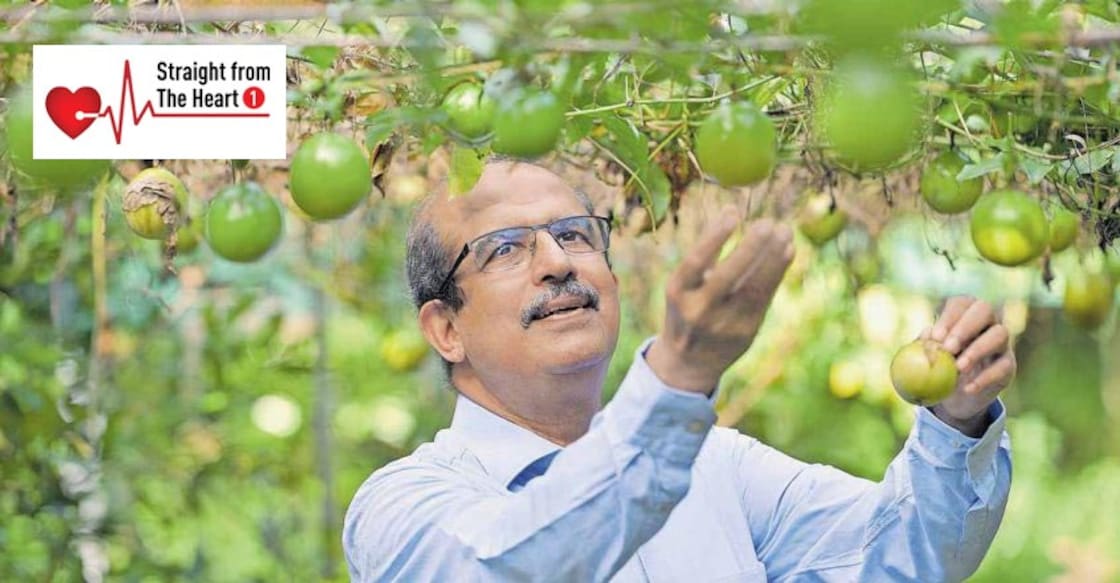

Dr Jose Chacko Periappuram, who made history by performing the first heart transplant in Kerala, starts sharing experiences that touched his heart...

The 36-year-old who climbed to my second-floor room of the Haripad Huda Trust Hospital will always stay in my mind. Abraham, who gave me the opportunity to sew memorable pages into the history of medicine.

All that the young man with a weak voice and difficulty in breathing had were lingering concerns about life. Abraham, who had to return from a desert land due to health problems, was living with a heart that was not responding to treatment.

When I said, ‘Abraham, your heart that has lost its strength will have to be replaced with another one for you to return to normal life,’ his answer was contrary to what I expected. “I know,” he said.

A doctor had earlier told Abraham, who had only two or three months left to live with his heart, that only a heart transplant surgery could prolong his life by a few years. So it was easy for him to understand our suggestion.

A heart transplant surgery was rare in India, and in Kerala, it was just a dream. All the doctors who worked with me had concerns if the surgery could be performed successfully.

The only know-how I and my colleagues Dr Saji Kuruttukulam and Dr Vinodhan had was what we had obtained during the limited training we had undergone at the famous Papworth Hospital in England. It was Dr Varghese Pulikkan, the then director of the Ernakulam Medical Trust, who helped us go beyond those limitations.

I noticed a board in his cramped room that said, ‘The only thing that can prevent you from going forward is you, no other obstacle can.’

His decision that the hospital itself will bear the entire cost of the first heart transplant surgery in Kerala and its follow-up treatment was crucial to the whole process.

The days and weeks that followed were busy as we conducted tests on Abraham and made arrangements for the heart transplant surgery.

There were many who said this wouldn’t happen in Kerala and those who tried to discourage me by saying any failure would be a great shock. But, I later realised that an invisible force was giving me the courage to overcome it all and move forward.

Anxious days

Abraham's health began to deteriorate day by day. Forget walking and climbing stairs, he couldn’t even lie down properly due to difficulty in breathing.

Abraham, who in his younger age could swim across the Pampa river, plunge into the water and return to the shore holding a big fish between his teeth, could not get out of his bed even for basic tasks. We even wondered if we would make it to the heart transplant stage, even he started doubting if he could.

What Abraham wanted was the heart of a healthy man of his own blood type and his own body type.

Only a person who has been brain dead in an accident and is on a ventilator and who neurosurgeons, following scientific tests, have declared will never return to life, can donate a heart.

It is cruel to ask the permission of a family grieving an unexpected loss to donate the organ of a dear one. But, during his last moments, the donor Sukumaran’s wife and children, perhaps, hoped that by donating his heart, they would be able to keep his memories and vitality alive.

Heart filled with goodness

Sukumaran was from a rural area near North Paravur. A sudden vehicle accident while he was cutting tender coconuts by the roadside left him unconscious. He was taken to many hospitals and was finally brought to the Ernakulam Medical Trust Hospital.

It is not that I didn’t wonder if I would be crossing the limit in talking about organ donation to the wife and children of Sukumaran who was confirmed brain dead.

It must have been the couple’s decision during their wedding to donate their eyes and kidneys if the need arose that probably inspired Padmini amidst the tragedy to donate her husband's heart.

Everything that happened later was mechanical and, to some extent, dramatic.

Arrangements were made to bring Abraham from Haripad in a friend's taxi at night, a journey of about three hours. At that time, doctors were preparing for the first heart transplant in Kerala. Dr Vinodhan, the head of anaesthesia, and Dr Jacob Abraham, his assistant, were busy setting up two operating theatres.

I and my colleague Dr Rajasekharan (he was later appointed the head of cardiac surgery at Alappuzha Medical College; Dr Rajasekharan passed away three years ago. Tributes to him) were constantly discussing the basics of surgery with the nurses and other team members.

The world over, a heart transplant surgery is usually performed by a medical team divided into two groups — one for heart donation surgery and the other for heart transplant surgery. But here the discussion was about how to make transparent the rare situation of a team of only two people who will have to perform two surgeries either one after the other or do both procedures alternately at the same time.

Abraham reached the Medical Trust around 8pm. Explaining the delay, Abraham said he took the time to eat his favourite dish of parotta and beef on the way to the hospital.

I believe his desire to eat his favourite food stemmed from, perhaps, his apprehension about the success or failure of the surgery.

The historic day

May 13, 2003. Time, 10pm. The atmosphere was calm. Preparations for Abraham's surgery were completed in one operating theatre. Donor Sukumaran was brought to the next operation theatre. Those were anxious moments.

Spiritual Father Ansel also came from Kannamkunnam church. We the doctors, the nurses, the other colleagues, the directors of the hospital... Father Ansel’s prayer... An unexpected thunder and lightning that occurred while praying for god's favourable intervention surprised everyone. We accepted it as a sign portending success.

Father Ansel took a silver cross wrapped in plastic paper, blessed it and and handed it to me and said: ‘Doctor, keep this cross in your pocket. It should be taken out of the pocket only after the surgery.’

As instructed by him, the cross remained in the right pocket of my surgical dress, supporting me and my heart, providing me courage until the end of the surgery.

I was terrified by the possibility of Abraham’s heart stopping during surgery. The heart was affected so much due to its inability to function. A heart four times bigger than expected. A heart that pumps only 10% of expected blood, the trepidation caused by doubts about whether the heart will beat until it is attached to the lung regulator.

Abraham's inactive heart was removed after Sukumaran's heart was arrested, covered in cold solution and ice and placed in a container. From time to time, I reminded the silver cross in my pocket about my prayer that my hands should move in the right direction during the surgery. As each chamber of the heart was stitched one after the other, each blood vessel was stitched together, my only wish was for that heart, which had preserved Sukumaran's life for 42 years, to throb in Abraham's body.

After an hour and 47 minutes, when Abraham’s new heart started beating, my mind froze and seemed to be in a state of indifference, probably a reflection of the uncontrollable joy and satisfaction I experienced.

It was past midnight when Abraham was disconnected from the machines and shifted to the ICU. As I was sitting on the bed detached, a cold hand tapped my shoulder. My colleague Dr Rajasekharan held my hands, congratulated me, and asked me in my ear, "Sir, it was a lie when you told us that this was the first time that you were performing a heart transplant, wasn’t it?”

A surgery that I had never performed, a surgery that was the first in the state, a surgery that would have been the most disappointing turning point in my professional career had it failed… I bowed my head to that almighty invisible force that helped us perform it without the slightest of problem, that led me during the surgery.

The hero of this historical event was not me, not Abraham, not the doctors or nurses who worked with me. The most heroic act was that of Padmini, and her children, who agreed to share her husband’s heart even during the moments of grief caused by his unexpected, untimely separation.

We must bow to their goodness. I believe then and now that most of the credit for the medical history that was created in Kerala must go to Padmini and her family.